Almost 90% of coal plants must close to limit global heating to 1.5C, report warns

Report says coal demand should peak this decade if countries want to stick to their net zero plans

Global coal use must be slashed by 90 per cent by 2050 if the world is to meet its net zero goals and limit global heating to 1.5C, a new report warns.

The report, released by International Energy Agency (IEA) amid energy talks at Cop27 in Egypt, reveals staggering data on the dependence on coal in several countries despite ambitious climate action goals announced by leaders.

It calls for a steep reduction in the use of the fossil fuel, including crucial policy changes this decade, for the world to avoid the catastrophic impacts of the climate crisis. The planet has already warmed by almost 1.2C on pre-industrial levels.

The report models several scenarios for a decline in the use of coal, which is the dirtiest of all fossil fuels and responsible for a big share of planet-heating carbon emissions, in the next few years.

Under all circumstances, the report states that the coal demand is set to peak this decade if countries stick to their announced targets.

Under existing net zero commitments, the decline in use would be close to 70 per cent by 2030, it states. And if all countries adhere to IEA’s net zero scenarios, the decline should be about 90 per cent by 2050.

The global power sector, which is the biggest consumer of coal, should be completely decarbonised in advanced economies by 2035, and worldwide by 2040, the report states.

“Over 95 per cent of the world’s coal consumption is taking place in countries that have committed to reducing their emissions to net zero,” said IEA executive director Fatih Birol.

“Coal is both the single biggest source of CO2 emissions from energy and the single biggest source of electricity generation worldwide, which highlights the harm it is doing to our climate and the huge challenge of replacing it rapidly while ensuring energy security,” Dr Birol said.

“But while there is encouraging momentum towards expanding clean energy in many governments’ policy responses to the current energy crisis, a major unresolved problem is how to deal with the massive amount of existing coal assets worldwide.”

Despite recurrent narratives of imminent decline or renaissance, the report found that global coal demand has been stable at near record highs – averaging around 5,500 million tonnes per year – for the past decade.

If nothing is done, existing coal plants would emit 330 gigatonnes (330 billion tonnes) of carbon dioxide from 2022 to 2100, more than the combined historical emissions from coal plants and two‐thirds of the remaining budget to limit warming to 1.5C by 2050, according to the IEA.

“This latest IEA report paints a challenging picture, but not one that any of us should be surprised by,” Sir David King, chair of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group, said.

“Given the state of the climate emergency, we must have a chance at keeping warming below the 1.5C limit. To achieve this we need urgent and radical action to change course.”

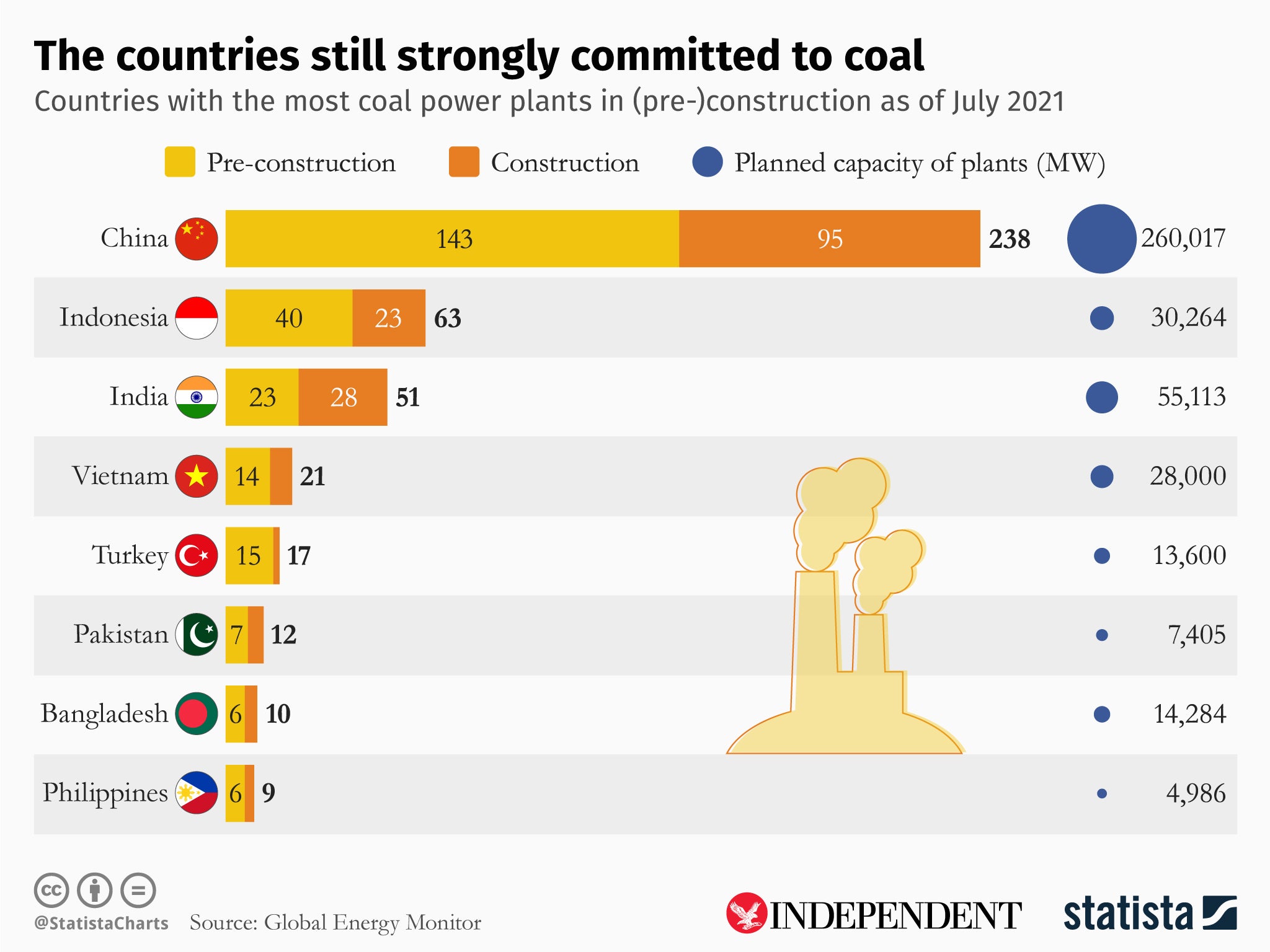

However, the transition will be most challenging in countries such as China, India and other Asian economies where the dependency on coal is high.

Several coal-dependent countries have also witnessed a rebound due to power security issues this year caused by Russia’s war on Ukraine and extreme weather events such as heatwaves and droughts.

Today, there are around 9,000 coal-fired power plants around the world, representing 2,185GW of capacity. China accounts for over half of that output, according to the IEA.

Reaching net zero emissions requires reductions in emissions from all fuels, including oil and gas. However, a rapid decline in unabated coal use is inevitably a central feature of all pathways to a more sustainable energy system.

Sir David said the only way the “radical” transition needed from the global South can be achieved “in a just and orderly fashion” is with an “appropriate loss and damage package agreed. It is of the utmost importance that Cop27 deliverers this as a matter of urgency”.

The momentum for growth of natural gas use in developing economies is slower than in previous editions of the World Energy Outlook, notably in south and southeast Asia, putting a dent in the credentials of gas as a transition fuel.

“The IEA leaves no room for doubt: to send coal emissions plummeting by 90 per cent by 2050 from the plateau it is currently stagnating, governments in developed countries need to build a decarbonised power sector by 2035 and 2040 in the rest of the world,” said Pieter de Pous, programme lead on fossil fuels at think tank E3G.

“It shows that coal-to-clean transition is ‘mission possible’ if finance is deployed creatively to retire coal plants early,” he added, saying that this should “inspire confidence: in governments involved in a just energy transition”.

Two heavily coal-dependent countries, South Africa and Indonesia, have announced Just Energy Transition partnerships with wealthier nations in recent days. The plans aim to help developing economies get finance to move to renewable sources.

The Indonesian announcement on Tuesday should be “the final piece of Indonesia’s puzzle to accelerate its energy transition”, said Dr Achmed Shahram Edianto, Ember’s analyst based in Indonesia.

Meanwhile, India and China, two of the biggest consumers and producers of coal, have ambitious targets to decarbonise the energy sector but haven’t committed to a target for a complete phase-out of coal.

This story was published with the support of Climate Tracker‘s Cop27 Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments