Charlie Hebdo defiantly tests limits of free speech as terror trial begins

The decision to republish the inflammatory cartoons that prompted the 2015 attacks on the opening day of court proceedings has reignited old debates, writes Anthony Cuthbertson

On Wednesday morning, as 14 people accused of orchestrating the deadly terrorist attack on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo prepared to stand trial, the top trending term on Twitter in France was #JeNeSuisPasCharlie.

The hashtag was a direct contradiction of the slogan “Je suis Charlie” – I am Charlie – which had trended worldwide in the wake of the 2015 attacks in solidarity with victims and the publication.

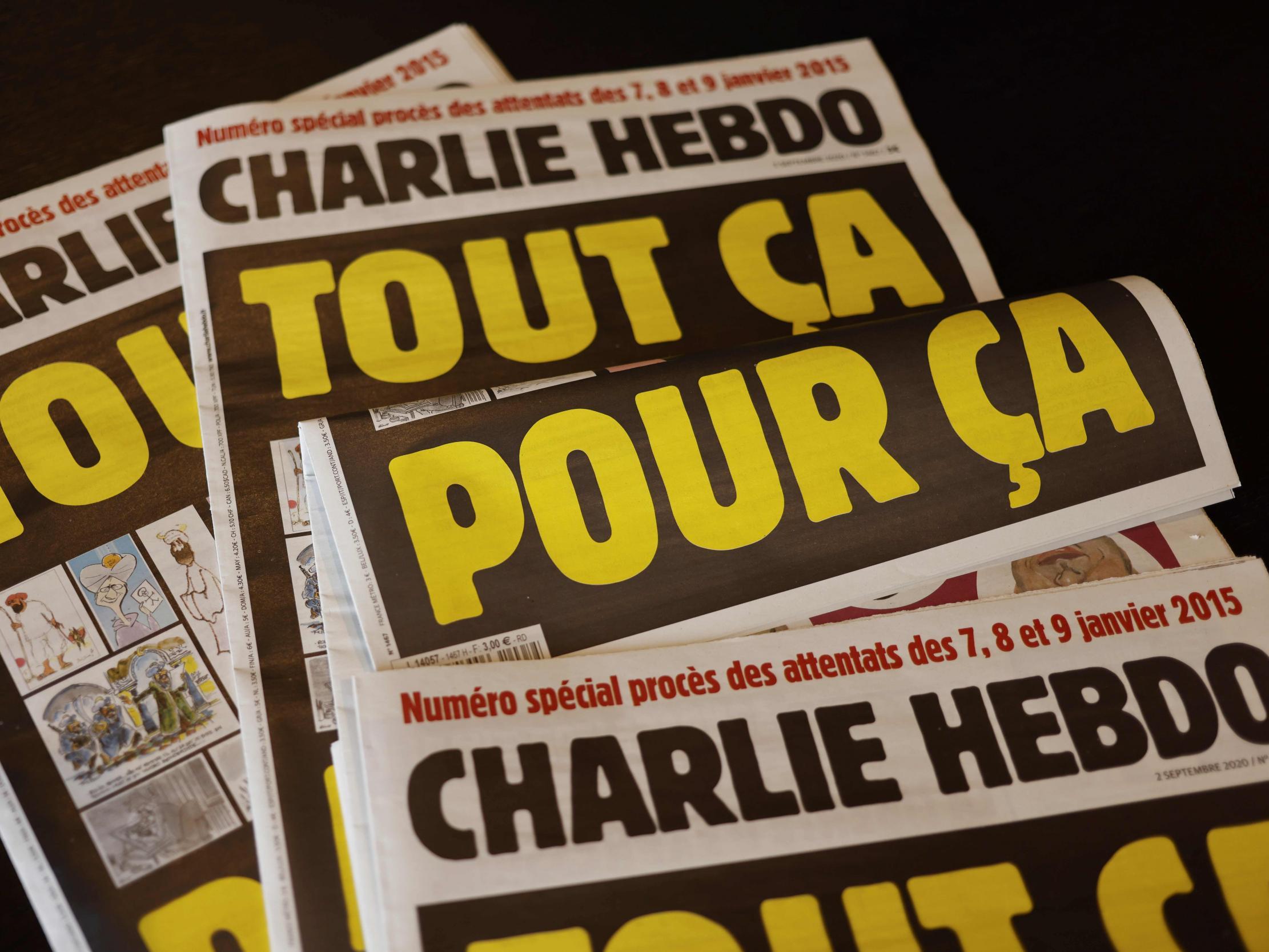

The apparent reason to defy such sentiment at such a sensitive time was the magazine’s controversial decision to republish a series of inflammatory cartoons ahead of the trial that had provoked the attacks five years ago.

The cartoons depicted the Prophet Muhammad, which is considered blasphemous by many Muslims, together with the headline: “All that, for this.”

People on social media criticising this decision claimed it was a deliberate act to insult Muslims and incite violence, while supporters said it was a necessary statement of defiance against terror and those who try to threaten freedom of expression.

French president Emmanuel Macron said he refused to condemn the publication of the cartoons, which is not illegal under French law.

Speaking on a visit to Lebanon, he said: “It’s never the place of a president of the Republic to pass judgement on the editorial choice of a journalist or newsroom, never. Because we have freedom of the press.”

The 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks, which began in its Paris offices and ended in a shootout in a supermarket two days later, left 17 people dead and dozens more injured.

Over the next 50 days or so, 144 witnesses will be called to give evidence, in a trial that has already seen old tensions revisited while resurfacing the debate surrounding free speech in France.

Among the victims of the 2015 attack was Charlie Hebdo editor and cartoonist Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnier, who was considered the face and figurehead of the provocative publication.

Just two days before he was gunned down alongside his colleagues, Charb had finished writing an 82-page essay on Islamophobia, which staunchly outlined his belief in freedom of expression while simultaneously calling out racists and explaining how he viewed the difference between anti-Islam and anti-Muslim.

The intention behind the cartoons, he wrote, was not to stoke hate but to shine a light on it through humour.

Charlie Hebdo has not published depictions of the prophet Muhammad since 2015, stating that it would not do it just for the sake of it.

In a statement following Wednesday’s publication, the editorial team wrote that it was now “essential” to republish them at the advent of the trial.

“We have often been asked since January 2015 to print other caricatures of Muhammad. We have always refused to do so, not because it is prohibited – the law allows us to do so – but because there was a need for a good reason to do it, a reason which has meaning and which brings something to the debate,” it stated.

“We will never lie down, we will never give up.”

It is a sentiment that could have come from Charb himself. Just two years before his death, he said: “We have to carry on until Islam has been rendered as banal as Catholicism.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments