Gone and quickly forgotten: World shrugs shoulders at fall of Boris Johnson – except for Ukraine

The prime minister’s departure has made headlines across the world as well as at home, but as a collection of The Independent writers around the world have found, there will be little regret globally for end of his time as British leader

It is not just the Westminster stage that Boris Johnson has announced he is exiting, it is also the global one.

His resignation means he will no longer appear at any more all-important, high-profile summits and meetings.

Instead, world leaders will have to deal with a new prime minister. And it is probably the case that few countries or leaders will miss him, except for one.

Ukraine

If there is a place that laments the downfall of Boris Johnson, it is Ukraine.

There he is the most famous foreign leader, bar President Vladimir Putin. In virtually every interview, from civilians fleeing frontline cities to defence officials, Boris is praised as Ukraine’s closest ally.

Ukrainians even took to social media to congratulate him on surviving a vote of no-confidence in June.

There has been genuine confusion among those The Independent have interviewed in the past few days over why Britain would want to get rid of a “such a great man”.

And so for Kyiv, the domestic turmoil which has forced Mr Johnson to finally step down, may deal quite a blow.

A large part of this adoration is due to the fact that Mr Johnson is among the only foreign leaders to have made two surprise visits to President Zelensky in Kyiv, the last in June. The Ukrainian leader said Thursday’s news had been met with “sadness” in Kyiv.

Just last week, the UK announced a further tranche of £1bn in military assistance to Ukraine. That brings the UK’s total military and economic support to an eye-watering £3.8bn, making the UK second only to the US.

The UK was also among the first nations to supply arms to Ukraine early on, including Nlaw anti-tank weapons, M270 Multiple Launch Rocket Systems and short-range Brimstone missiles.

Because of this and the perceived role Mr Johnson has played in rallying Europe around Ukraine he has become a celebrity in the country.

He was made an honorary citizen of the strategic port city of Odesa. Several Ukrainian towns have already reportedly announced plans to rename streets after him.

In fact, a June poll by Conservative peer Lord Ashcroft found that in Ukraine Boris Johnson was almost as popular as President Zelensky, beating US president Joe Biden and miles ahead of the French and German leaders.

MPs and officials say he set the “highest benchmark” internationally in terms of support of Ukraine and was leading the fledgling international coalition against Putin.

They hope that whoever comes next will meet those standards and even surpass it.

But with Mr Johnson accused of neglecting the UK’s most pressing domestic woes and the government collapsing so spectacularly, whoever follows him will have to focus on consolidating the leadership again and on everyday household concerns. This may eclipse Ukraine, Russia and a war which is 3,000km (1,865 miles) away.

Bel Trew in Dnipro, Ukraine

France

A “48 hours of circus” is how one French paper described the build-up to Boris Johnson’s resignation on Thursday.

It was a fitting finale for a prime minister once dubbed “un clown” by French president Emmanuel Macron. More than 50 resignations in two days saw increasingly incredulous media commentators in France wonder how much longer Johnson could continue overseeing “le chaos total”.

Some even compared his stubbornness to relinquish power to that of Donald Trump – another populist who Macron has been forced to deal with during his time in the Elysée.

With Mr Johnson responsible for spearheading and executing Brexit, his relationship with his europhile counterpart was always going to be fractious.

Accused of “making a mockery” of UK-France relations over his handling of the migrant crisis, Mr Johnson also oversaw a stand-off over fishing rights and dangled the prospect of breaking international law by triggering Article 16 of the Northern Ireland protocol.

All of this meant that the UK leader was blamed for fostering arguably the worst cross-Channel relations since the time of Napoleon. But the recent G7 and Nato summits had brought hope of improvement, united by their stance on the war in Ukraine, as well as shared security and economic interests.

Mr Johnson and Mr Macron once enjoyed a late-night whisky together, and were planning the first bilateral summit between the two countries since 2018. But while “Le Bromance”, as the PM’s aides reportedly called it, may be over, his departure will bring fresh hope for a new entente cordiale.

Anthony Cuthbertson in Paris, France

USA

Boris Johnson’s demise after just a few short years as the UK’s head of government won’t have much of an impact on relations between America and constitutional monarchy it severed ties with nearly 250 years ago.

On foreign policy matters, fears that Mr Johnson’s ascent could portend strains in the transatlantic alliance, largely came to naught thanks to former president Donald Trump’s defeat at the hands of Joe Biden, with whom the outgoing prime minister worked to bring the US, UK and her Nato allies more closely together than they’ve been in decades, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Though Mr Johnson has in many ways tried to tie himself to the Ukraine conflict with several high-profile trips to Kyiv, it has been Mr Biden who has taken on the lion’s share of responsibility in keeping Nato leaders unified, culminating in last week’s announcement that Sweden and Finland would receive unanimous consent to join the alliance after Turkey dropped previous objections.

Mr Biden and his aides have largely kept mum as the prime minister’s political fortunes waned over the last few days.

In response to questions about whether the US had any concerns over the tumult, the answers have characterised Mr Johnson’s troubles as an internal political matter.

But the White House maintains that the impending change in leadership will not have any effect on the strength of the “special relationship”.

Speaking aboard Air Force One en route to Cleveland on Wednesday, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre told reporters that the US “partnership with the United Kingdom continues to be strong”.

Andrew Feinberg in Washington DC, USA

India

The saga of resignations before Mr Johnson’s decision to step down attracted rolling coverage on Indian news channels and online platforms, where the analysis focused on the impact of potential changes in No 10 for relations between the two countries.

Indian newspaper editorials were scathing about Mr Johnson’s handling of Partygate and other ethics scandals, while almost all leading media outlets carried explainers for their readers on Britain’s convoluted parliamentary procedures.

There was visible enthusiasm around the prospect of former chancellor Rishi Sunak – whose wife and parents are Indian – being a possible successor to Mr Johnson, with the nationalist news website OpIndia gleefully describing him as “favourite to become the next PM”.

It was also noted that the cascade of resignations began with Indian-origin Mr Sunak and Sajid Javid, who has Pakistani parents.

India’s leading Hindi news channel Aaj Tak compared Mr Johnson’s situation to that witnessed in the state of Maharashtra in recent days, where a state government was toppled following a rebellion from its own assembly members.

Mr Johnson’s departure has split social media in India largely along ideological grounds, seen as bad news by the supporters of prime minister Narendra Modi, who has often claimed to have warm ties with Mr Johnson.

The news was welcomed by Modi critics, however, who have been resharing images from Mr Johnson’s April visit to India when he rode on a bulldozer.

The images were slammed as tone-deaf during a time when bulldozers were becoming a symbol of oppression against Muslims in India.

For many here, particularly on the liberal left, this will be Mr Johnson’s only enduring legacy.

Stuti Mishra in Delhi, India

Middle East

When it came to the Middle East, Boris Johnson’s tenure will mostly be remembered for being forgettable. He saw the region as a receptacle for UK weapons and a filling station for fuel.

In the wake of his resignation, his Middle East enemies gloated but not too effusively, and those considered friends shrugged.

As prime minister, Mr Johnson reliably kowtowed to Israel, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. He drew the ire of Palestinians for taking positions deemed too pro-Israeli. And he railed against Iran and its allies.

He drew criticism for failing to do enough to win the release of UK hostages, including Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who came home on his watch after his own disastrous comments as foreign minister were used against her.

In all fairness, he showed consistent apathy when it comes to human rights issues elsewhere in the Middle East, including Egypt and the Gulf States.

The UK was conspicuously absent when Western embassies banded together to call on Ankara to release dissident Osman Kavala.

In one piece of potentially creative foreign policy, Johnson appeared to seek to use Turkey as a post-Brexit economic counterweight to the European Union. But that effort floundered.

Mostly Johnson submerged the UK’s Middle East policies within those of the United States. Though he visited Turkey, Israel and elsewhere during his tenure as foreign secretary, since taking over as prime minister almost three years ago, he made stopovers to only two countries in the Middle East – Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

The constrained travel schedule was the result of coronavirus travel restrictions that halted travel in 2020 and 2021, but it also likely underscored Johnson’s lack of interest.

Both countries are big suppliers of oil and big customers of Western weapons, the mainstays of the UK’s Middle East policy.

Borzou Daragahi

South America

The announcement of the forthcoming resignation of Boris Johnson dominated the headlines in Latin America, but noticeably absent were reactions from the leaders of the region.

That should come as little surprise, given the fact that the relationship between the United Kingdom and Latin America has been almost non-existent since 1930, when the interests of both took different paths as a result of the world re-ordering and Britain replaced as the dominant power in the region by the United States.

Despite attempts by both sides to increase economic ties, in practice trade between Britain and countries in the region is very limited.

As foreign minister, Boris Johnson visited Peru, Argentina, Chile and Brazil with the idea of discussing greater collaboration in the areas of international security, defence and commercial opportunities.

After Brexit, Johnson repeatedly expressed his desire to strengthen ties with Latin America, but the sentiment turned to nothing.

Beyond the Falklands War with Argentina in 1982, Great Britain has had little strategic influence in the region.

Diplomatic ties remain cordial but somewhat distant, so Johnson’s resignation will produce more headlines but little change.

María Luisa Arredondo, assistant editor, Independent en Español

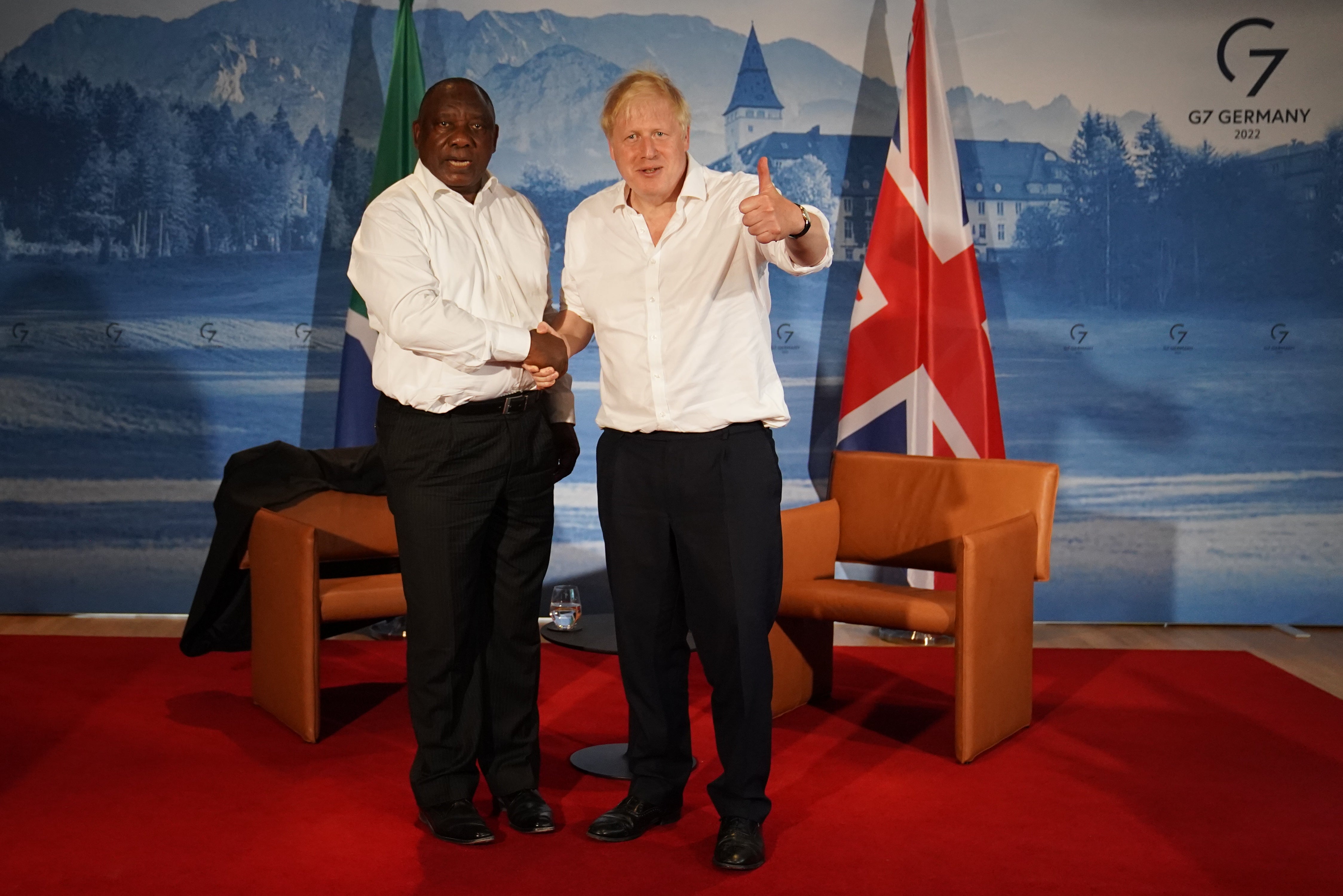

Africa

Boris Johnson’s patchy record on Africa since 2019 did not pacify those who resent his racially-insensitive past comments about the continent.

The outgoing prime minister previously lamented the end of the colonial era, downplayed the impact of slave trade and suggested Barack Obama – a hugely popular figure on the continent – disliked Britain because of his Kenyan heritage. As prime minister, he only visited the continent once, right at the end of his premiership, for last month’s Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting.

Africa policy under Johnson has been a mixed bag. His decision to abolish the Department for International Development negatively affected some of Africa’s most vulnerable during the coronavirus pandemic. Meanwhile, the UK’s travel “red list”, which included vast swathes of Africa, was derided as racist.

While Johnson has overseen a rise in immigration from certain African countries, particularly Nigeria, the UK did not list a single African university on a new scheme to fast-track work permits for highly-educated immigrants, angering the continent’s elites.

Meanwhile, Johnson’s most prominent Africa policy, the Rwanda migration deal, was bungled and the intense backlash from rights groups and opposition politicians in the UK left the Rwandans frustrated.

Alex Vines, head of the Africa programme at Chatham House, said Johnson had, however, improved bilateral ties with Kenya. Vines also told The Independent that the admission of Togo and Gabon to the Commonwealth were “encouraging”.

But Johnson’s failure to overhaul UK-Africa relations comes as countries ditch traditional loyalties and pursue closer ties with the likes of China and Russia, a trend Johnson appeared unable or unwilling to reverse.

Charlie Mitchell, in Nairobi, Kenya

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments