How Bogota is using infrared night-vision cameras to save its ‘toxic’ river

Nearby residents washing, bathing and watering their crops with the river's extremely toxic water are now suffering from a whole host of diseases, reports Genevieve Glatsky in Bogota

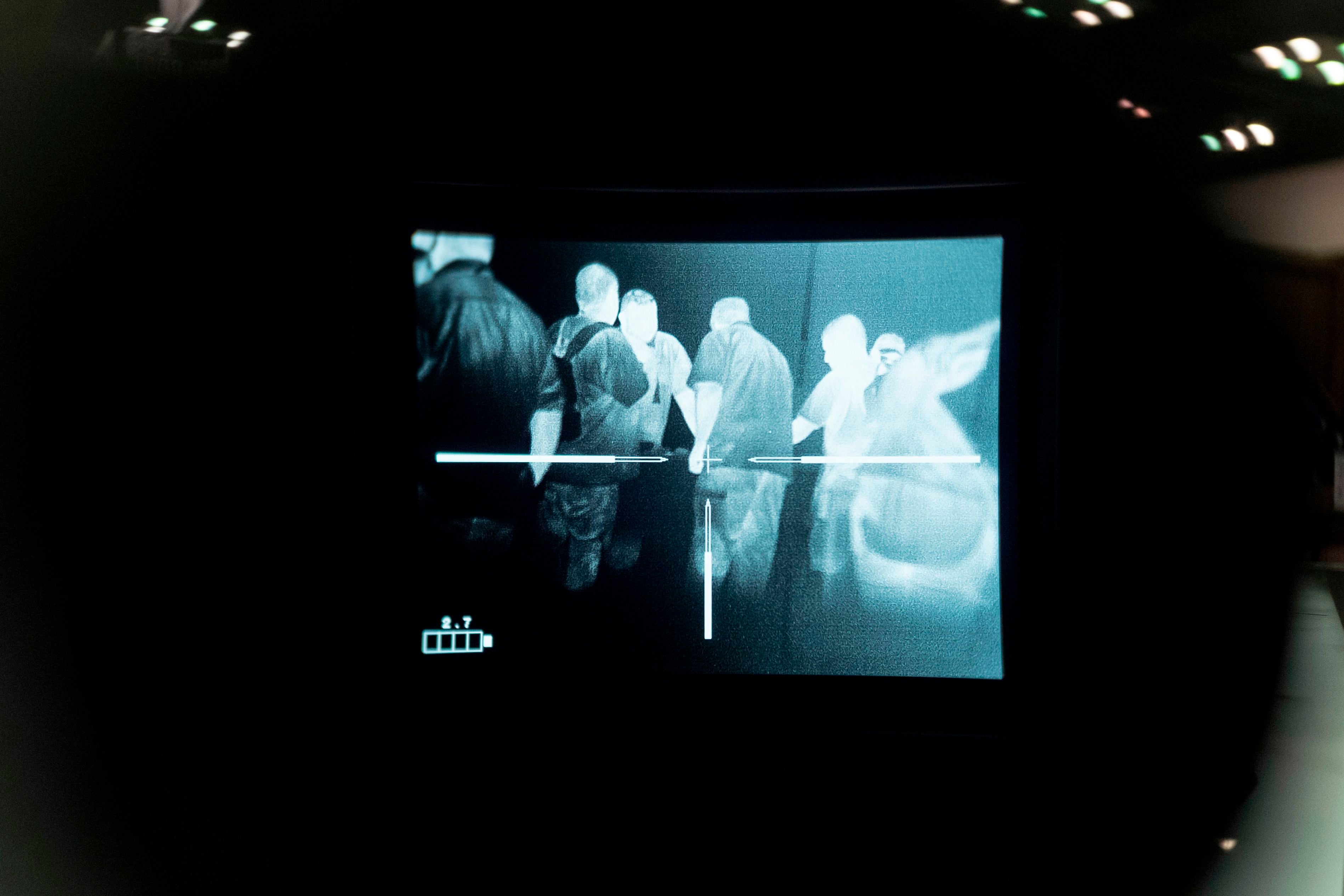

At a waste-water treatment plant on the northwest edge of Bogota, Mireya Avila Teuta watches eight screens alternating between rainbow-colored thermal images.

In an upper right screen, the environmental sanitation technologist spots a man lighting a fire, most likely burning cables to extract the valuable copper inside. As the rubber melts, the open fires spill toxic by-products into the river.

That right there, she points out, is one of the crimes she is on the lookout for.

The city’s water and sewage utility was established in 1955, when the population was about 894,000. As the city has grown to include approximately 11 million people, its waste treatment and sewage system has failed to grow with it. Now, some 690 tonnes of waste flow into the river daily.

In 2014, a historic court order called for the river’s decontamination, but progress has been slow.

Fernando Vasquez, director of the Al Verde Vivo Foundation, recalls how in 1997 he and a group of 40 multidisciplinary researchers traversed the river for the first time in rafting boats over 15 days.

As they moved down the channel, watching it grow darker and the smell of “s**t and rot” grow more putrid, they observed that the toxic chemicals had killed off so much of the river’s aquatic life that there was a lack of oxygen, and increasing amounts of organic waste were releasing methane, causing small explosions.

“During the tour we found that the river has had zero oxygen for many years in the city of Bogota,” says Vasquez. “It is a dead river. It is a totally toxic river.”

That polluted water is then used to irrigate vegetables, Vasquez points out, going into broccoli, carrots and cabbages that line grocery shelves.

“When you buy them in a store or supermarket, a label does not tell you what water that lettuce has been produced with,” he says. “So it’s a public health problem.”

This room is the central monitoring station of the BochiCar system – a network of solar-powered cameras with infrared and night-vision technology that covers 100km of the 375km Bogota River and is designed to detect environmental crimes threatening the city’s ancient river.

Inspired by a similar system in Israel, the cameras are meant to prevent such crimes as open-air fires, cattle farming, drug use and illegal dumping in a river known to have seen cars, sofas, television screens, tires and even dead bodies floating on its waters.

Claudia Campos, a microbiologist at Javeriana University, has found in her research – some of it funded by the city’s sewage utility – not only the presence of bacteria, viruses and parasites in the river, but concentrations of heavy metals and harmful micro-organisms in the water, soil and crops in neighbouring communities.

The quality of the water, she found, correlated with respiratory, diarrheal and skin diseases in residents living near the river, who washed, bathed and watered their crops with the toxic water.

Campos found that many of the communities in close proximity to the river were economically disadvantaged and lacked access to public services and education about the risks of contamination or their rights under the law.

“It is very common that in some of these people we surveyed, children or adults frequently have diarrhoea, but they almost assume that as part of their life as something that happens to you periodically,” she says. “Some go to the doctor, others do not, but there is really no movement that supports these areas so that they can claim the rights to have a river that is in better condition so that it does not affect them.”

The 14 points of the BochiCar system located along the Bogota River throughout the city have thermal imaging technology that allows them to detect fires from more than 7km away. The central monitoring station is located in the Salitre Wastewater Treatment Plant, where authorities then pass on the information to authorities to take appropriate punitive measures, ranging from fines to jail time.

“What it does is generate institutional presence where people realise that there is someone who is watching them and persuades them to decrease crimes throughout the area,” says Gerardo Romero, technical coordinator of the 2014 Bogota River judgment.

But this system is not foolproof. Deibis Velasquez, a patrol officer, pointed out that a fire in February 2020 in Bogota’s southernmost neighbourhood of Soacha burned for three days before authorities arrived to put it out, despite an early warning alert from the thermal cameras.

Amaury Rodriguez, director of the Fund for Environmental Investments of the Bogota River, says that the BochiCar system is also part of a broader effort to build walking paths, plant trees and promote the area around the river. He hopes that in time people will see the river not as a crime-infested dumping ground but as a tourist site and family-friendly destination for bike riding and bird-watching. So far they have built 50km of paths and planted 120,000 trees, most of them native species.

It is a dead river. It is a totally toxic river

“It’s a matter of improving poor planning and a cultural issue as well and an issue of environmental awareness,” says Rodriguez. “You know those are big challenges.”

And the BochiCar system is just one of the many projects undertaken in the last few years to improve the quality of the river, including mega-work treatment plants, deforestation projects, and private sector collaborations.

Nelly Villamizar, the magistrate of the river and the judge behind the 2014 court decision, says that at the heart of the problem of the river’s putrid waters is the city’s corruption and lack of urban planning. Without an adequate city sewage system or enough functioning treatment plants, she says, waste water ends up getting dumped directly into rivers and streams.

“The authorities weren’t paying attention; they weren’t being careful,” says Villamizar. “And the river became polluted; the city grew; the money was stolen.”

Monica Sanz, a biologist and representative of the verification commission of the Bogota River judgment, recalls growing up in Bogota hearing her parents and grandparents fondly reminisce over stories of swimming in the river. She wondered then why people kept dumping waste into it, and why no one was doing anything about it.

She would go on to do her doctoral research about the tanneries on the banks of the river, and came to conclude that the government was focusing more on engineering solutions instead of engaging with the ecology and communities of the river basin.

“A river is a living body. It’s not only a sewer or a flow of water,” she says.

Campos, the microbiologist, says she finds it shameful that so many entities with so much information capacity have not been able to summon the coordination to clean up the river.

“What is worrying is that so many studies have been carried out on the Bogota River, and so many court decisions have been issued that it’s assumed that activities are being carried out to recover the river, but it is still a tremendously slow process,” she says. “It’s so slow and the river is so bad and so many years have passed for it to still be such a polluted river.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments