‘I thought my head was exploding’: How eye injuries have become a gruesome global punishment for protest

With the rise in ‘less-lethal’ weaponry across the world, more and more demonstrators are paying a terrible price for speaking up, as Naomi Larsson and Charis McGowan report from Santiago, Chile

When she hit the ground, Nicole Kramm remembers thinking to herself: “Not my eye”. The 29-year-old photographer was in central Santiago in Chile on New Year’s Eve, documenting as well as celebrating alongside others in a plaza that had been the heart of months-long protests.

Since 18 October, Chile’s uprising had been brutally repressed by police and the military. Human rights groups have accused the state of deliberately injuring protesters using crowd control weapons like tear gas and rubber bullets.

By New Year’s Eve, 359 people – including protesters, bystanders and journalists – had been shot in the eye with these so-called “less-lethal” weapons and two people were blinded completely. As the months went on, the number of eye injuries rose to more than 460.

In an interview with The Independent, Kramm recalls how the night sky lit up with flashes of fireworks and the atmosphere was jubilant – a welcome change to violent clashes with police during months of demonstrations over chronic inequality and government mismanagement.

But at some point the atmosphere turned. As Kramm walked through the plaza, she didn’t see that a line of officers had begun firing projectiles into the crowds.

A buckshot pellet robbed Kramm of 90 per cent of the vision in her left eye. After the impact, she reached up to feel her face, then began shaking uncontrollably when she saw her hand was covered in blood. “I thought my head was exploding and my brains were coming out,” she recalls.

Kramm believes the Chilean police shoot directly at eyes as a tactic to stop protests. “It’s an effective and systematic form of repression. When you’re hit in the eye they immobilise you without killing you,” she says.

Kramm continues to attend trauma therapy for the psychological damage she sustained – she still has nightmares about that night. But she is also determined to do something about it. Alongside hundreds of others who have been similarly wounded, she has joined the Assembly for Ocular Trauma Victims, a group lobbying for justice and police reform.

Sebastian Zembrano, 19, joined the group after a tear gas canister fired during protests in October smashed into his right eye, blinding him. The injury changed his life completely – he suffers headaches and episodes of fainting, which have forced him to abandon his studies. “I can’t concentrate on the letters,” he says. He used to support his country’s security forces but is now emphatic in his belief: “The police need to be reformed.”

For activists, journalists, protesters and rights groups, the eye has become a symbol of resistance. With the rise of “less-lethal” weaponry, losing your sight can be the price of expressing your voice.

Experts say the use of KIPs (kinetic impact projectiles, a category including rubber and plastic bullets, bean bag rounds, sponge rounds and pellets) has increased worldwide, a disturbing pattern of police negligence and brutality that has left thousands blinded.

“In many cases, particularly in Chile, the authorities clearly set out to injure their victims as a tactic to punish and deter them from demonstrating,” says Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International. “This is an outrageous and sinister threat to freedom of expression and the right to peaceful assembly.”

“I’m unimaginably upset that there are a lot of us,” says Linda Tirado, a 36-year-old photojournalist from Nashville in the US. She is one of 30 people across the country who has been shot in the face and partially blinded during the recent wave of anti-racism protests, in what the American Academy of Ophthalmology has called a “medical emergency”. The foam bullet that hit Tirado detached two of the muscles that control eye movement in her left eye, and then burst the globe. The impact of these bullets on the eye is like a hammer hitting a grape.

Dr Rohini Haar, an emergency physician and fellow at Berkeley Law’s Human Rights Centre, of the University of California, has researched death and injury from KIPs globally. She describes the use of these weapons as “a systemic form of brutality”.

“The failure of the US government and most governments to regulate their use, and the frequency and pervasiveness of the use of these weapons is systematic,” she tells The Independent.

Tirado took photographs of the police moments before she was blinded by what she believes to be a compressed foam bullet. They are “the last photos [she] took with two eyes”. Three months after the incident, she’s still trying to make sense of it.

“I hate to say that it was intentional, but I don’t really see another interpretation of the photo evidence that I have,” she says. “I wasn’t in a crowd or protest scrum. They had to have meant to hit me – whether they meant to hit me at centre mass or in the head.”

According to international guidelines, KIPs should only be directed at the lower body “of a violent individual when a substantial risk exists”. But research has shown these projectiles are “inherently inaccurate at longer distances” and are “likely to be lethal” at close range.

Indeed, the pattern of eye injuries suggests widespread misuse and abuse by authorities across the world.

In Kashmir, India, thousands have been blinded during clashes between protesters and security forces. Between 8 July and 15 September 2016 alone, the SMHS hospital in Srinagar received approximately 635 patients with eye injuries caused by pellets.

In France, at least 24 people lost eyes after the gilets jaunes movement erupted in 2018.

And as of December 2019, Gaza’s Ministry of Health reported that 50 protesters had been shot in the eye since demonstrations began in March 2018.

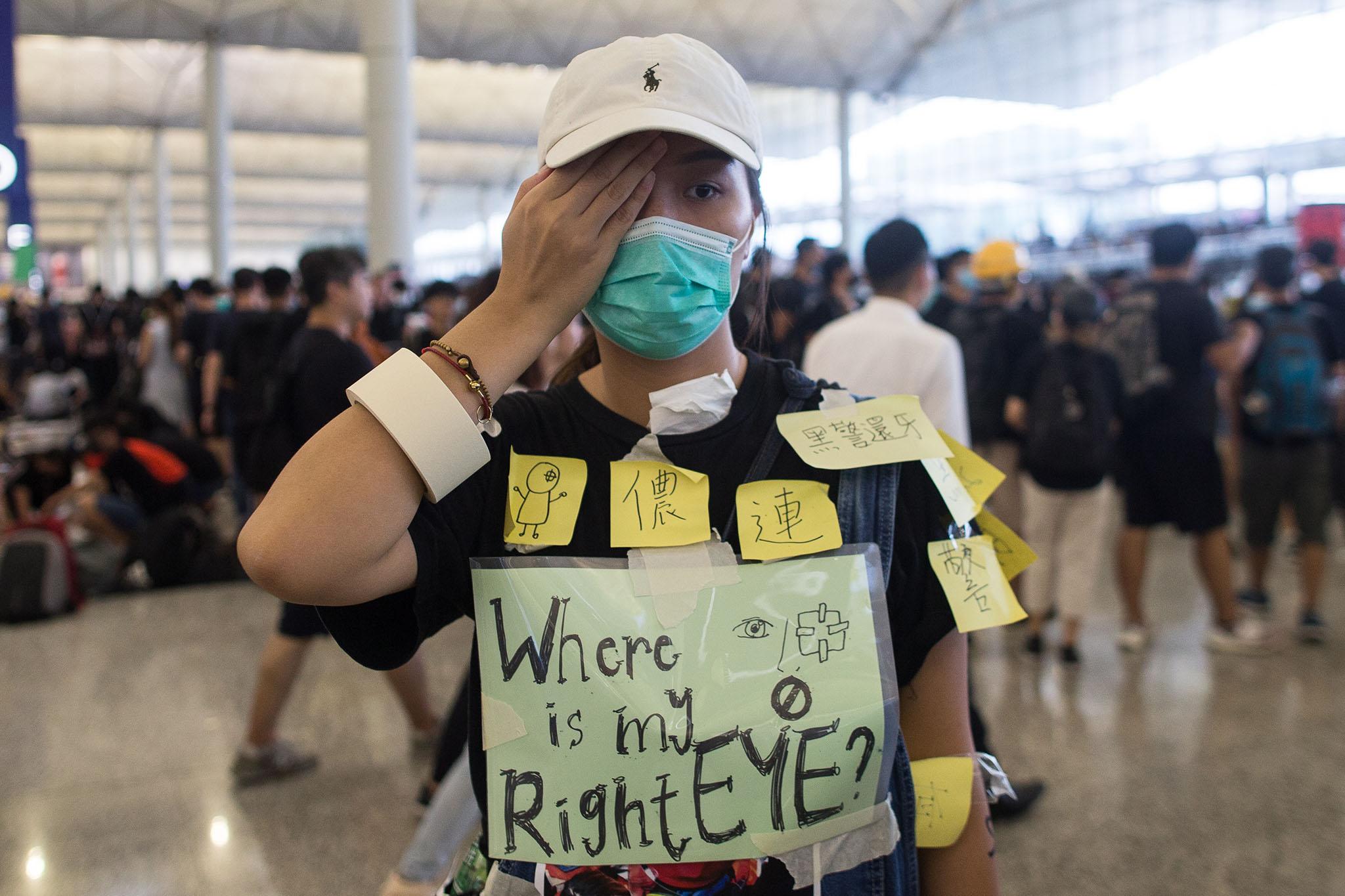

A year ago in Hong Kong, a young woman wearing a blood-soaked bandage became an unofficial figurehead of the demonstrations after being shot in the eye.

And most recently, on the night of 8 August when tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Beirut in the wake of the devastating explosion, the American University of Beirut Medical Centre treated seven people – all under the age of 30 – for eye traumas. It was the same number of eye injuries they had seen on the night of the blast itself.

It shocked Dr Bahaa Noureddine, the chair of the hospital’s ophthalmology department. “They are not coming from battle. They are just young men and women. These weapons should not be used against protesters.”

While incidents are on the rise, there have been examples of horrific injuries caused by KIPs ever since they were first introduced by colonial Britain. Half a century ago, when the British brought rubber bullets to Northern Ireland during the Troubles, three people were killed before they were replaced by plastic “baton rounds” – thought to be safer, although still killing more than a dozen people between 1975 and 1989.

Many were blinded by rubber bullets during the Troubles. Richard Moore was 10 years old when a rubber bullet hit the bridge of his nose. A British soldier had fired into a school playground in Derry, destroying Moore’s right eye and permanently blinding his left eye.

It continues to horrify and sadden him that these weapons are still used on civilians, 48 years later.

“It’s a real injustice,” he tells The Independent. “It’s criminal what they’re doing. They shouldn’t pretend people using those weapons can be managed and controlled. Anybody using those weapons is intent on causing serious injury. Nobody can deny it now.

“The impact of what happened that day stays with you. The rubber bullet is with me every day.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments