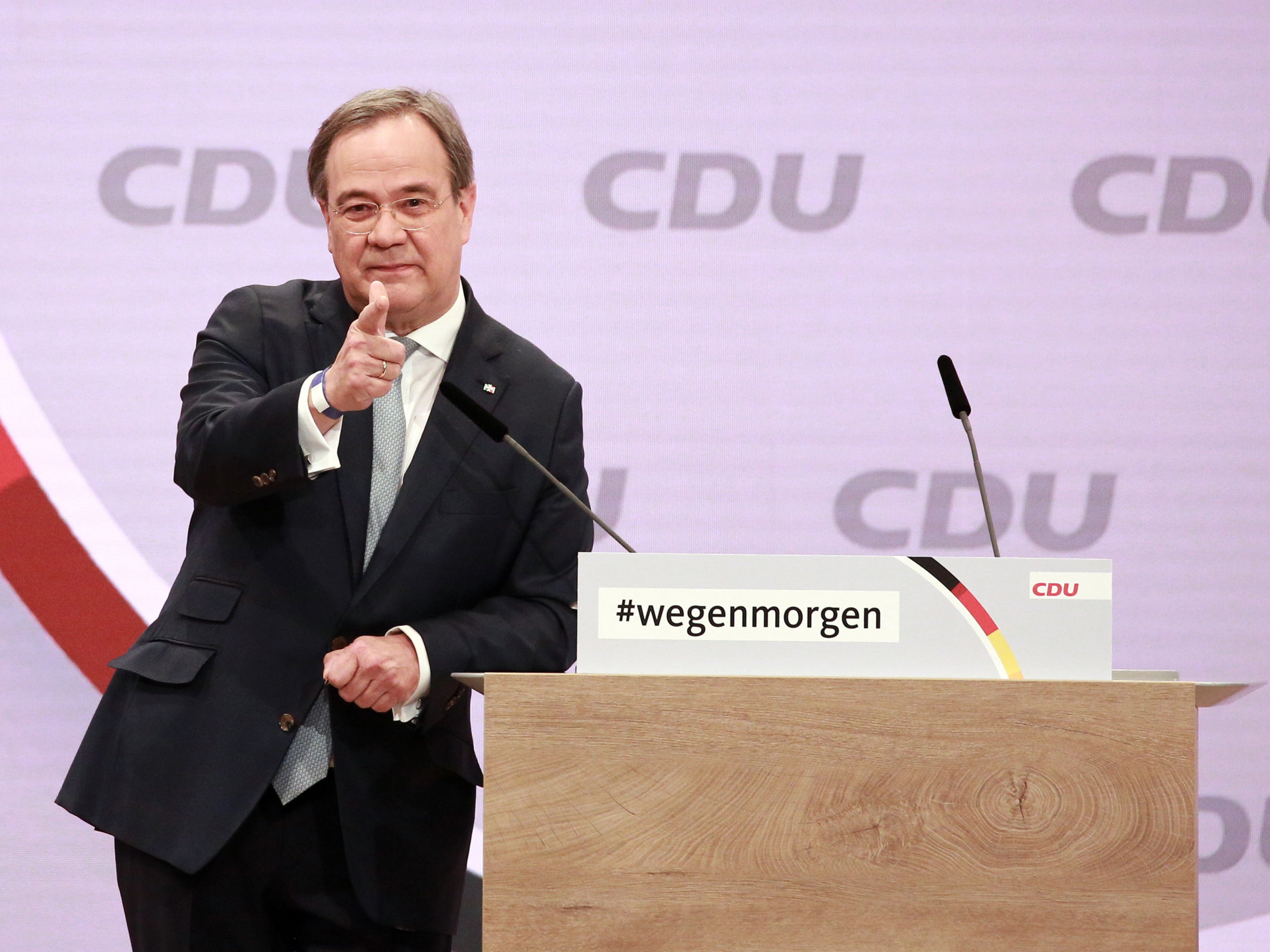

Armin Laschet: The man who could replace Angela Merkel

Is Laschet what Germany, Europe and the world need right now, asks Sean O’Grady

If all goes well for him, the unprepossessing figure you see here will be the chancellor of Germany by the end of the year. Probably the best way to think of Armin Laschet is as someone with the moderate, pragmatic political outlook of Angela Merkel, plus the cross-party deal-making skills of Joe Biden, but combined with the irreverent, mischievous, slightly clownish personality of Boris Johnson.

Laschet is the recipient of an award for levity, which he accepted in evening dress wearing an enormous harlequin hat and a mock medal. Carnivals are his thing, as jovial and boozy as you like. The British prime minister would surely relish an invite. In any case, Laschet will be hoping that this blend will impress German voters when they go to the polls in September, plague permitting. The question is: is Laschet what Germany, Europe and the world need right now?

It is not certain, and this unathletic figure will have to clear some formidable hurdles before he can take power and lay claim to be the heir to Adenauer, Kohl and Merkel (who between them have run the federal republic for 46 of its 72 years).

Laschet has done well for himself so far, effectively winning his party’s leadership and succeeding Merkel at the head of Germany’s Christian Democrats, still ahead in the polls after being in power, albeit often in coalition, for 16 years. At their recent party conference (much delayed by Covid), Laschet narrowly beat off strong challengers for the party leadership. He benefited greatly from being known to be the man Merkel wants to follow her. He has been a staunch and sincere defender of her policies, especially over taking a million refugees from Syria a few years ago, an act of extraordinary political bravery on her part. He has also been blessed by some luck. Chancellor Merkel’s previous anointed successor and party leader, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, stood down last year, having failed to impress the public. The party has been looking around for a fresh, inspirational leader ever since, and found it surprisingly difficult, given the prize.

Since 2017, Laschet has been premier of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), the most populous state in the federal republic, and has been knocking around German politics for about three decades (he turns 60 next month). In the final round of voting in the recent convention, he squeaked in with 52.7 per cent of the vote of the party’s representatives, against Friedrich Merz, having dispatched Norbert Rottgen in the first round. Although the trio had their own strengths and weaknesses, they were also disappointingly monotonous in background – besuited, male, sixtyish, Roman Catholic Rhinelanders, and lawyers by trade. Rottgen has a reputation as a bit of a vote-loser, and Merz is considered arrogant by some. So the job is almost Laschet’s by default.

However, under the German system, the Christian Democrats will soon have to nominate a candidate for chancellor in the federal elections in the autumn. The task will be undertaken by both the Christian Democrat Union, which operates in 15 of the 16 states, and by its sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU), which looks after Bavaria, the richest one. In this round, Laschet will have to face down his Bavarian rival and state premier, Markus Soder, as well as a possible late challenge from another CDU figure, the 40-year-old federal health minister, Jens Spahn, gay and politically conservative, less the trad centrist than Laschet. Spahn has said Merkel “perhaps put too much emphasis on the humanitarian approach” over the Syrians.

This – the choice of chancellor candidate – does represent something of a crossroads. Laschet is so at ease with migration and a more diverse Germany that he acquired the nickname “Turkish Armin”, a reference to Germany’s largest minority group. Soder by contrast is on record as saying “the Germans do not want a multicultural society”. While Merkel (and Laschet) were welcoming the Syrians fleeing war, Soder was attempting to close Germany’s borders. He has expressed the view that some migrants are impossible to integrate, and some can return to Syria when the war ends.

Soder also strikes a more Eurosceptic tone (by German standards) than Lascher. Put at its crudest, he does not see why the prosperous taxpayers of Munich, Nuremberg and Ingolstadt should be sending money off to support the likes of Greece and Italy (even if the Italians and Greeks then use it to buy BMWs and Audis made in Bavaria). In fact, he’d much prefer they send their tax euros to the poorer bits of Germany. Soder also backed a bizarre plan a few years ago to publish an annotated version of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, banned in Germany since the war. (It came to nothing in the end.)

Laschet, on the other hand, is as much a pan-European as that other prominent German Christian Democrat, Ursula von der Leyen (herself once briefly thought of as a successor to Merkel). Laschet comes from the land next to France and the Low Countries, a battlefield in the past, with all the European consciousness that comes with that history. His family’s origins lie in the Francophone Walloon region of Belgium, and his wife and childhood sweetheart, Susanne Malangre, also has close family links to Belgium. Her uncle was once CDU mayor of Laschet’s home town of Aachen. His son Johann, by the way, is a fashion influencer and model. Naturally enough, Laschet also spent six years in Brussels as an MEP. He thinks the president of the EU Commission should be elected by the people of Europe, and he is generally close to the French president, Emmanuel Macron, and the belief that the solution to the EU’s problems is “more Europe”, presumably including a European fiscal union, not a cause even Chancellor Merkel could support wholeheartedly. If Laschet does get to be chancellor, it will re-establish the Paris-Berlin axis around which everything in the EU will revolve. It could be the closest partnership since Helmut Kohl and Francois Mitterrand launched the euro project in the late 1980s, a single currency to create European unity (in theory).

Europe isn’t what it was back then, yet no one should underestimate how fundamental the European project is to German Christian Democrats and Germany’s political culture – an article of faith in fact, and bolstered by the fiasco of Brexit.

The Laschet-Soder choice will be difficult. Soder, though no Trump or Farage, does represent a more wary, cautious approach to further European integration, and might thus be more in tune with public opinion.

Soder fares better in the polls than Laschet, and, arguably, might be better able to steal votes from the far-right AfD, who usually run at about 10 per cent in the polls – though there will be no pacts or coalitions with a gang seen as neo-Nazi fruitcakes. Just possibly, the younger, less well known but dynamic figure of Spahn could come through the middle as a compromise candidate; Germany’s relatively successful record on Covid reflects well on him as health minister, and the EU’s, and Von der Leyen’s, perceived failures in the vaccines won’t help Laschet and the CDU old guard. So far Spahn has supported Laschet as virtually a running mate, but that might just change. The pair favour rebuilding the transatlantic alliance, but Laschet is also doveish towards Russia and China, which might provoke tensions with Washington. Laschet tends to allow his foreign policy to follow export orders.

The CSU has twice before held the national chancellor candidacy for the CDU-CSU, in 1980 and 2002, but the tilt to the right didn’t quite succeed, and they lost both times to the social democrats. Even if Soder did beat Laschet to the candidacy, German voters as a whole might not warm to him. Beyond that, as chancellor-designate Soder is probably less well equipped than Laschet to work with other parties to build a stable governing coalition. Knowing that, the Union might opt for the safer “continuity Merkel” candidate, and stick with Laschet.

German politics is certainly more fragmented than ever in its post-war history. The CDU-CSU “Union” can be expected to get about a third of the vote, which is poor by historical standards, but good by comparison with the current competition. The once mighty social democrats are down to about a fifth of the vote, about where the greens are, and reduced to being junior coalition partners with the Union. The rest of the vote is divided up between the AfD, Greens, ex-communist left and free-market liberals (FDP). Under proportional representation they will all probably gain seats in the Bundestag, and the horse trading will get messy, as indeed it will across the European Union and beyond in the coming years.

State elections in Baden-Wurttemberg, Rhineland, in March (scheduled) will be a further opportunity for the public to voice their opinions, but the Union seems sure to “win”, though it will be forced to rely on others to govern. Whoever ends up as chancellor of Germany will have to confront these untidy challenges, but also have to live in the shadow of their remarkable and durable predecessor. When Merkel took office in 2005, Tony Blair and George W Bush were her opposite numbers, and she can look back on a decade and a half of steering Germany through unprecedented peacetime difficulties, always preserving her party’s place at the centre of affairs. Her successor will find the job no less difficult.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments