What the sale of Wordle to The New York Times tells us about the world we live in

A young Brit working in New York comes up with a cute little puzzle game for his partner, then sells it for a seven-figure sum. It is a story with many messages, writes Hamish McRae

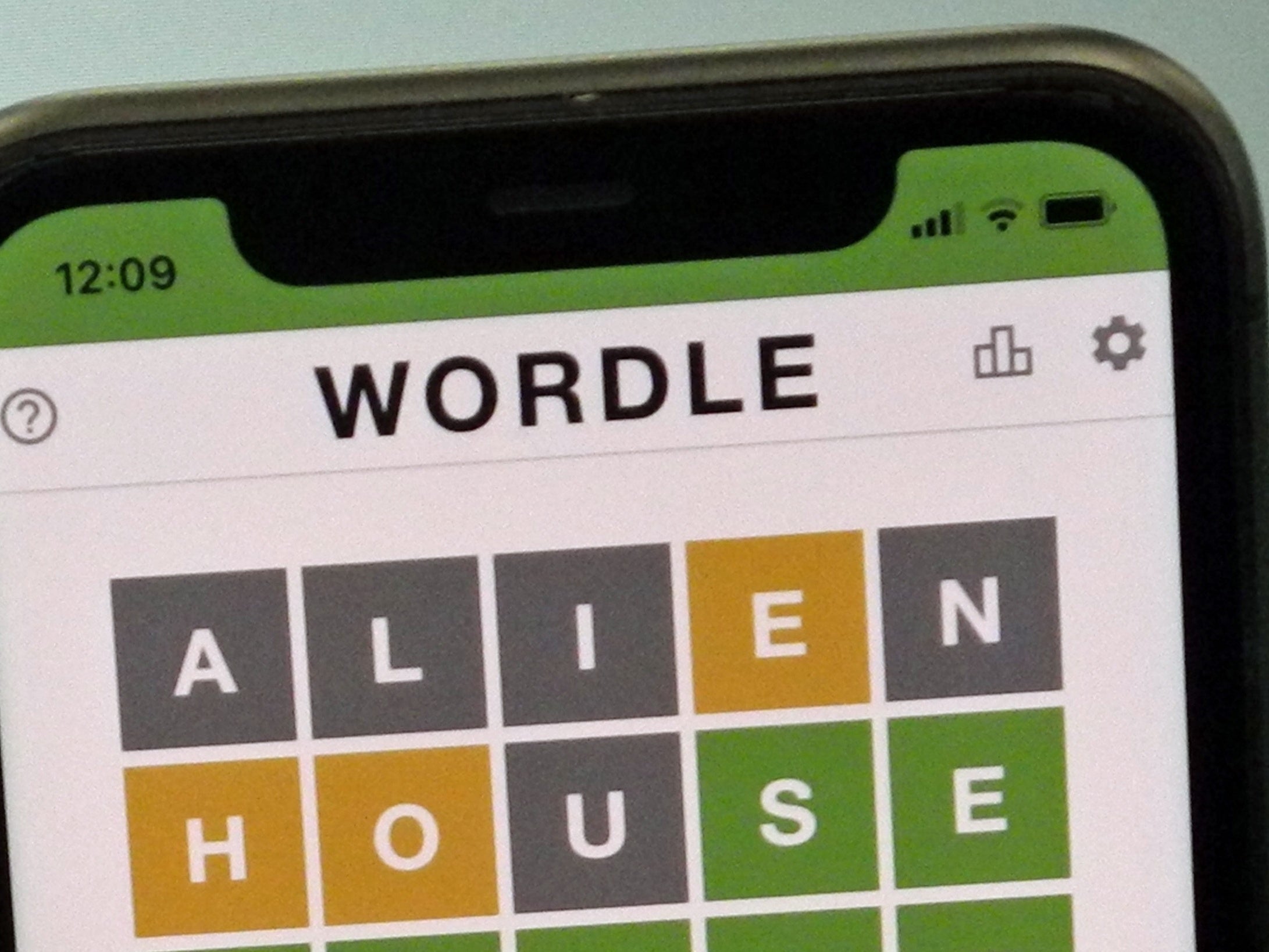

It is a tale for our times. A young Brit working in New York comes up with a cute little puzzle game for his partner. Within a few weeks it goes global and he sells it to The New York Times for a sum “in the low seven figures”. The game of course is Wordle, and its creator Josh Wardle – a clever play.

It is a story with many messages, things that it tells us about the world we live in now. Here are my top 10.

First and most obvious, it is story about the power of social media. It was back in 1881 that Ralph Waldo Emerson made his famous observation, which in shortened form was that, if you built a better mousetrap people would beat a path to your door. Now, thanks to social media, they get there much faster. What would have taken months and years happens in seconds and minutes. Wordle succeeded because people saw it as a better mousetrap.

Two, it shows the importance and possibilities of a side hustle. Josh Wardle created it in his spare time. Google “side hustle” and there is a wall of ideas about how people can make money out of their hobbies and a string of tales of people who have made fortunes that way. Again, this is an idea that has been around for many years – for journalists it is called freelance – but the sheer complexity of the modern economy has created many more opportunities.

Three, the explosion of social media has created huge competition for eyeball-time. How do you get someone’s attention when they are bombarded with other things to look at on their phones? These words you are reading here have to compete against a YouTube video, a WhatsApp from a friend, a TikTok clip, selfies, and on and on… One way of winning eyeball time is to create a game that people want to play, and Wordle is the latest example of that.

Four, great ideas come from smart people, not giant corporations. This was not created by Netflix or Disney, or indeed The New York Times. It needed no huge investment, indeed not really any investment at all – just one natural genius.

Five, America is still a land of opportunity for immigrants. Of course Josh Wardle could have emigrated somewhere else, for his skills as a software engineer would have been in demand everywhere. But after graduating from Royal Holloway, part of the University of London, he chose to do a further degree in the US. There he stayed. So ask yourself this: had he remained in Britain, or moved to Berlin, or wherever, is it likely that he would have had this success? Well, maybe. But I think it would have been tougher anywhere else.

Six, leading on from that, one of the great lures of the US – and this applies to the UK too – is the magnet of higher education. On the QS rankings published last month, the US had nine of the top 20, while the UK had five. Switzerland had two, Singapore two, and China two. There were no EU universities in the top 40.

Seven, the disruption of the pandemic has created opportunities that did not exist before. We have all shot up the learning curve in our use of electronic media and that has created an audience eager to try out new apps. It has given some people more leisure to do so, and demand has created supply. Without the pandemic I suspect Wordle might not have taken off.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices newsletter by clicking here

Eight, conventional media enterprises, such as The New York Times, need to find ways of boosting their reach. The paper acknowledged this: “The Times remains focused on becoming the essential subscription for every English-speaking person seeking to understand and engage with the world. New York Times Games are a key part of that strategy.”

Nine, there was a clear non-commercial intention of the game’s creator. He was not in it for the money, hence the choice of only releasing one game a day. He explained: “I’m just kind of suspicious of apps and games that want your endless attention. I worked in Silicon Valley. I know why they do that. With Wordle, actually, I kind of deliberately did what you’re not meant to do if growth is your goal ... I think people have an appetite for things that transparently don’t want anything from you. I think people quite like it that way, you know?”

I like that, but my final point I like even more. This is a love story. As The New York Times reported, he created this for his partner. They played it together for months. Then he introduced it to relatives. And only then, last October, he released it to the world.

That is the way things should be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments