The fortunes of the US economy have surprisingly little to do with whoever wins the election

There are good reasons to expect that the US economy will do rather well during the next decade, whether Trump or Biden is elected in November, writes Hamish McRae

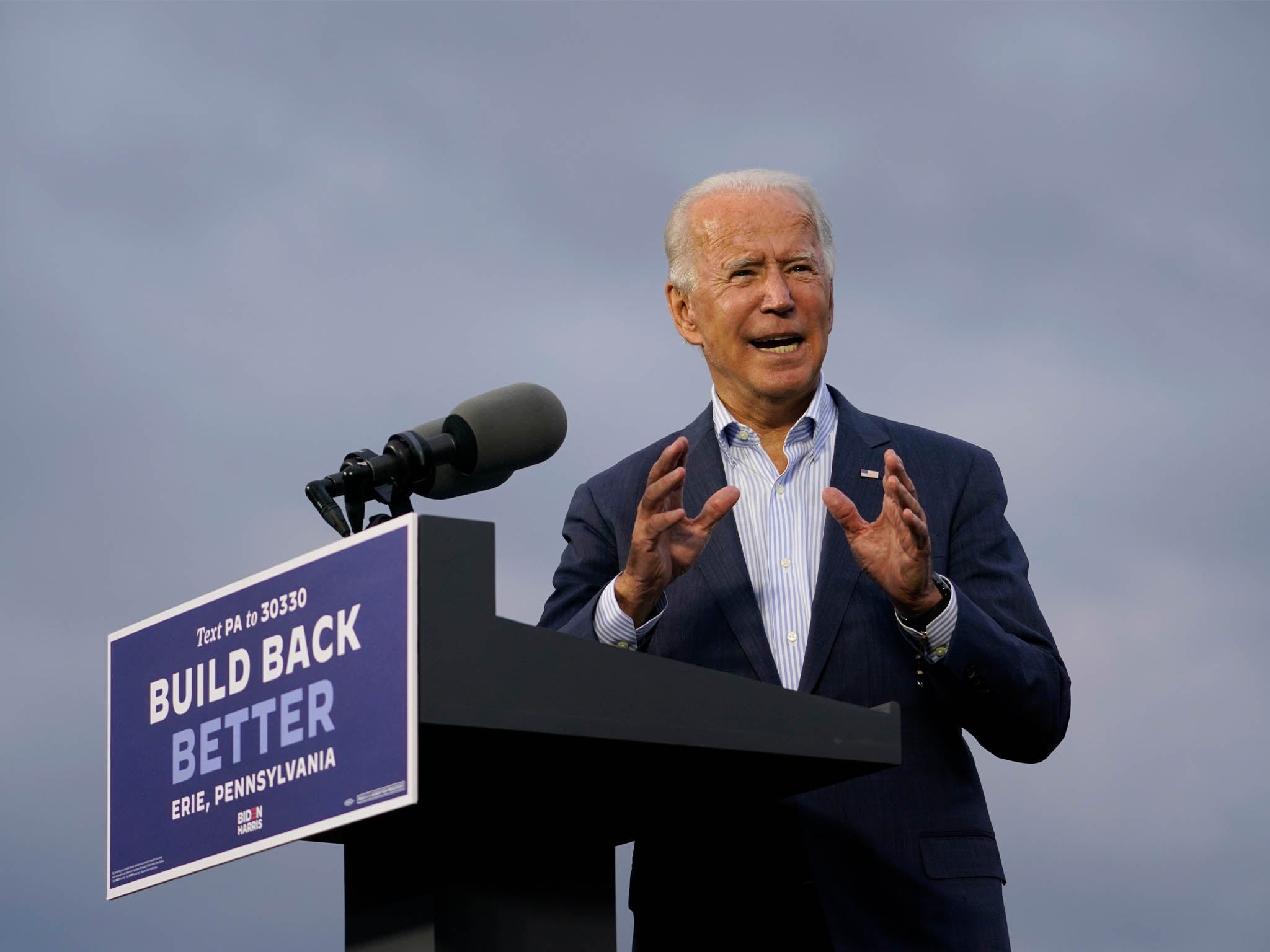

Three weeks to go in the US election and there’s an apparently widening gap. So what would a Biden victory do to the economy?

Here is a message of hope, but with a twist. There are good reasons to expect that the US economy will do rather well during the next decade, in particular lifting the living standards of the middle class. But, and here’s the twist, that will not have much to do with whoever wins the election.

It is easy to see what has gone wrong with the US economy over the past few years: a long boom, yes, but one whose benefits have been unequally shared. The tech billionaires have become ever richer, while people on middle incomes have seen their living standards stagnate. Job numbers have risen but so too has insecurity, while many people at the bottom of the income and wealth scales have sadly gone backwards. Donald Trump sought to reverse these trends, to rebuild middle America, but the reality is that the pattern has intensified. Inequality has risen, with the pandemic seeing a surge in the fortunes of the billionaires at the very time that unemployment has hit those on low incomes hardest.

So would a change in policy change things? Joe Biden has promised an increase in corporation tax and on the top rates of income tax, but – and it is unpopular with the left to say this – tax rates do not make a huge amount of difference to inequality. The big US corporations and the wealthiest individuals have been able to avoid taxation in various ways. The way companies such as Apple have used EU tax law to cut their tax bill is an example of the former. Donald Trump’s own tax affairs are an example of the latter. Fixing the tax system is not about higher tax rates. It is about much deeper and better thought-through reforms.

Besides, if you look at the big numbers of US monetary and fiscal policy, it hard to see much changing. The Federal Reserve has shown itself to be truly independent and there will be zero change in monetary policy, which will remain extremely loose. And at a macro-economic level, the US deficit is going to remain pretty stratospheric. The various experts have crawled over Joe Biden’s tax and spending plans and concluded that the outcome might be a slightly larger deficit than that of Donald Trump. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget concluded that a Biden Presidency would add $5.6 trillion to the deficit over 10 years, a Trump one just under $5tn. That difference is little more than a rounding error.

So what will change things? Observers from this side of the Atlantic tend to focus on the ways in which US policy differs from European models. They claim that if the US were to adopt more of the European tax and welfare systems it would be better able to tackle its social problems. The response of many Americans is to point to the difference in the performance of European and US economies, noting that over the past 30 years Europe has grown much more slowly than the US.

I don’t think it is helpful to get into this debate. What is worth saying is that both the US and to a lesser extent the European economies have spent 30 years facing two forces that have worked against the interest of their middle-income workers. China and India have added the thick end of a billion workers into the globally traded economy. And technology has hollowed out middle-skilled jobs. Both forces – and this is the really important point – are probably now waning.

The China/India point is simple enough. If the US imports something from China, the labour used to make it displaces US workers. If a UK bank uses a call centre in India, those are call centre jobs that otherwise would have been in the UK. This has been a dominant feature of the world economy for 30 years, but while it is not coming to an end it is becoming weaker. The size of the Chinese workforce is starting to decline as the one-child policy has reversed population growth, and while the Indian population will carry on growing, there seem to be limits on the impact of this on traded services.

The technology point is more complex. We cannot be sure, and everything is confused by the pandemic, but we seem both to be applying technology much better and appreciating where it cannot replace human activity. If this is right, there is at least a reasonable possibility that the hollowing-out of middle-skilled jobs will be coming to an end.

So will a Biden presidency (and let’s assume for a moment this will be the outcome) mark a turning point, an upward one, for the fortunes of the US middle class? Will real wages start to rise steadily instead of stagnating? I think so. But it won’t have much to do with whoever is in the White House.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments