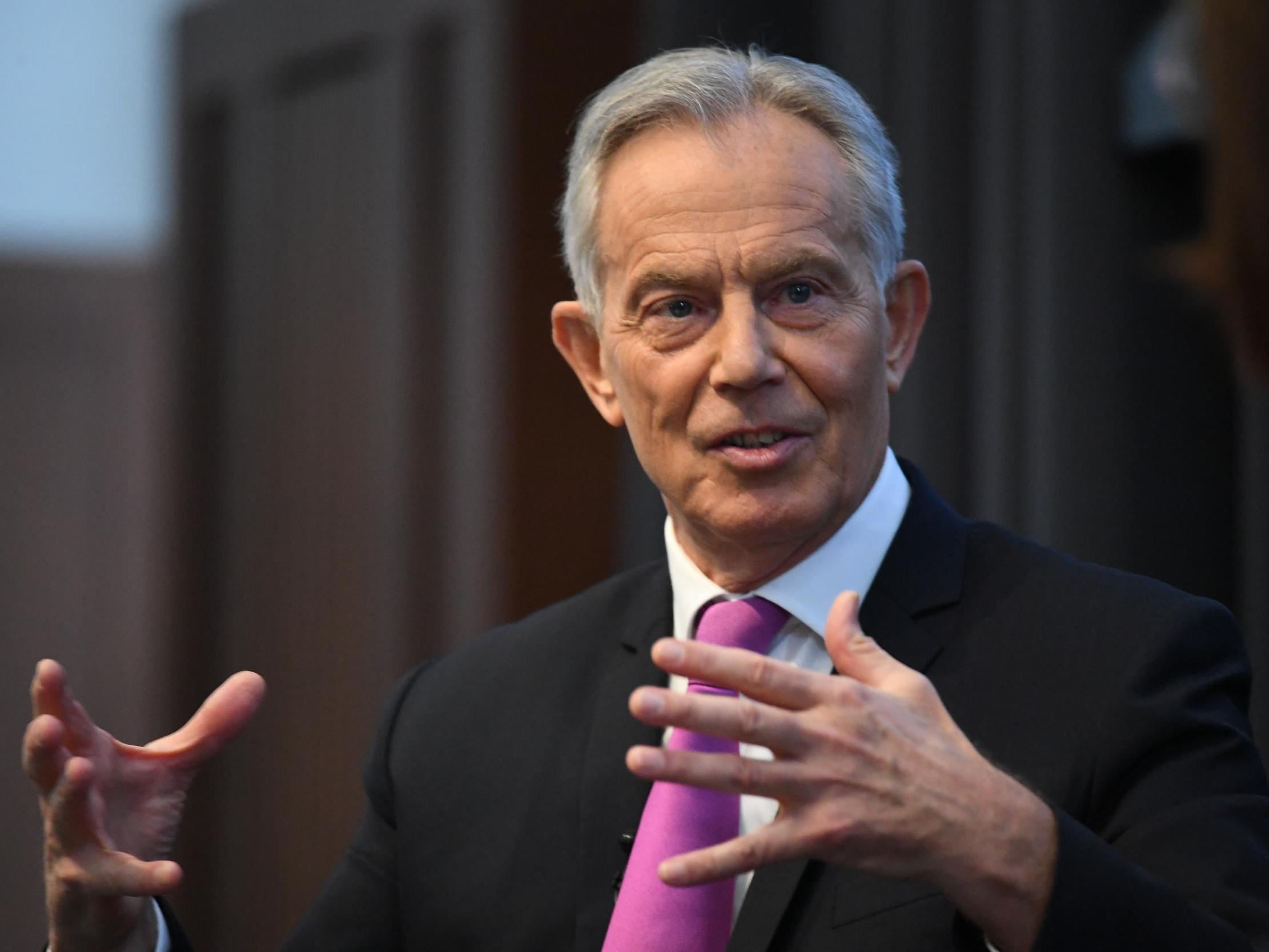

Tony Blair has told the Labour Party what it might – now – be willing to hear

The former prime minister has made clear that Jeremy Corbyn’s successor will have to redefine what ‘radical’ means, writes John Rentoul

It has taken a long time, but I think more and more members and supporters of the Labour Party are now interested in what Tony Blair has to say. Admittedly, today’s lecture at King’s College London was to an audience of Blairites, including family, friends and lots of people who used to work for him.

But there were also some students there, and I noticed quite a lot of surreptitious but emphatic nodding going on. It reminded me that the late Philip Gould, the Labour pollster, used to say that the aim of Blair’s speeches and interviews was to get people watching on TV “nodding along”. That has long been an exceptional skill of Blair’s – he said the Labour Party does “better when we are the calm voice of reason” – but he has been through a long period when most of the party wished he would just shut up and go away.

The election defeat in December has changed that. Although many Labour members don’t want to let go of their “radical” policies, they are open to debate about priorities and how to communicate them.

Which is why Blair’s urgent message today seemed well timed. His central argument was not that Labour should be more “moderate” – although, as he pointed out, that would help – but that it must redefine what “radical” means. He said: “We want to tackle inequality, promote social justice, redistribute power and deal with climate change, but that can’t be left to the politics of street protest.”

He argued, and this was his first “nodalong” moment, that this required Labour to adopt a “mentality of government”. He said: “The Labour Party is not an NGO, or a pressure group; its aim is not to trend on Twitter; or to win endorsements from celebrities – which are usually temporary, by the way.”

The party needs to be serious about the hard choices of government, he said, and laid into the comforting Labour myth that its policies are popular. “The voters did not like the policies,” he said, attacking “the fallacy of polling individual policies and thinking you’re learning something”.

He said there is a difference between a “three-second, a 30-second and a three-minute conversation”. The three-second version is: “Should the railways be nationalised?” To which the short answer is usually “Yes”. The 30-second version is about who is going to pay for it and whether other policies are more pressing, and the three-minute version has to consider the future of driverless cars and a zero-carbon transport system, in which the question of the ownership of one mode of transport falls down the order of priorities.

This was part of a wider problem with the manifesto, which he said he had read in full. The more you read, the less credible it seemed, he said. It seemed to have been compiled by saying “Yes” to every shadow minister who “knocked on the door and said here’s a 10-point plan and I want £1bn”. The voters could sense it, he said: “If you’re living a really tough life and someone promises you the Earth, it’s not credible.”

He clearly thought the current leadership campaign was failing to engage in this debate, and you could almost feel the frustration as he said: “I cut a lot of slack to those fighting a leadership campaign.” He knew what it was like, and accepted that he had not said, during his leadership campaign in 1994, for example, that he wanted to scrap the commitment to public ownership in Clause IV of the party’s constitution. “But no one was in any doubt that the party was going to change if I was elected.”

And he became animated when asked how he felt now that Sedgefield, his old seat, was in Tory hands: “I feel angry when the Labour Party refuses to do what’s necessary to win.”

He refused to be drawn on which candidate he supported for the leadership, saying he didn’t want to “damage” anybody. But he was critical of Keir Starmer, without naming him, by disagreeing with “people who say, ‘We’ve got to unite’ – the first thing is that you have to decide, then you can think about how to unite”.

He said he thought the party’s half a million members would divide: most want radical change and are open minded about how to achieve it; and then there is the “sectarian far left”, and he implied that the party would just have to wait for them to go away.

Typically for Blair, and despite the lecture being billed as a reflection on 120 years since the Labour Party was founded in February 1900, he hardly dwelt on history at all – except to make a familiar argument about seeking to reunite the Labour and Liberal traditions. This has always been about an attitude – an ambition to make the Lib Dems redundant by making the broadest possible electoral pitch – rather than a call for the parties to merge.

As ever, it is today’s politics that Blair is really interested in. He cannot resist analysing it, anticipating what is coming next – it’s the tech revolution, apparently, and it’s going to change everything – and saying what Labour should do in ways that get people nodding along.

But now, for the first time in more than a decade, I think many Labour people are ready to listen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments