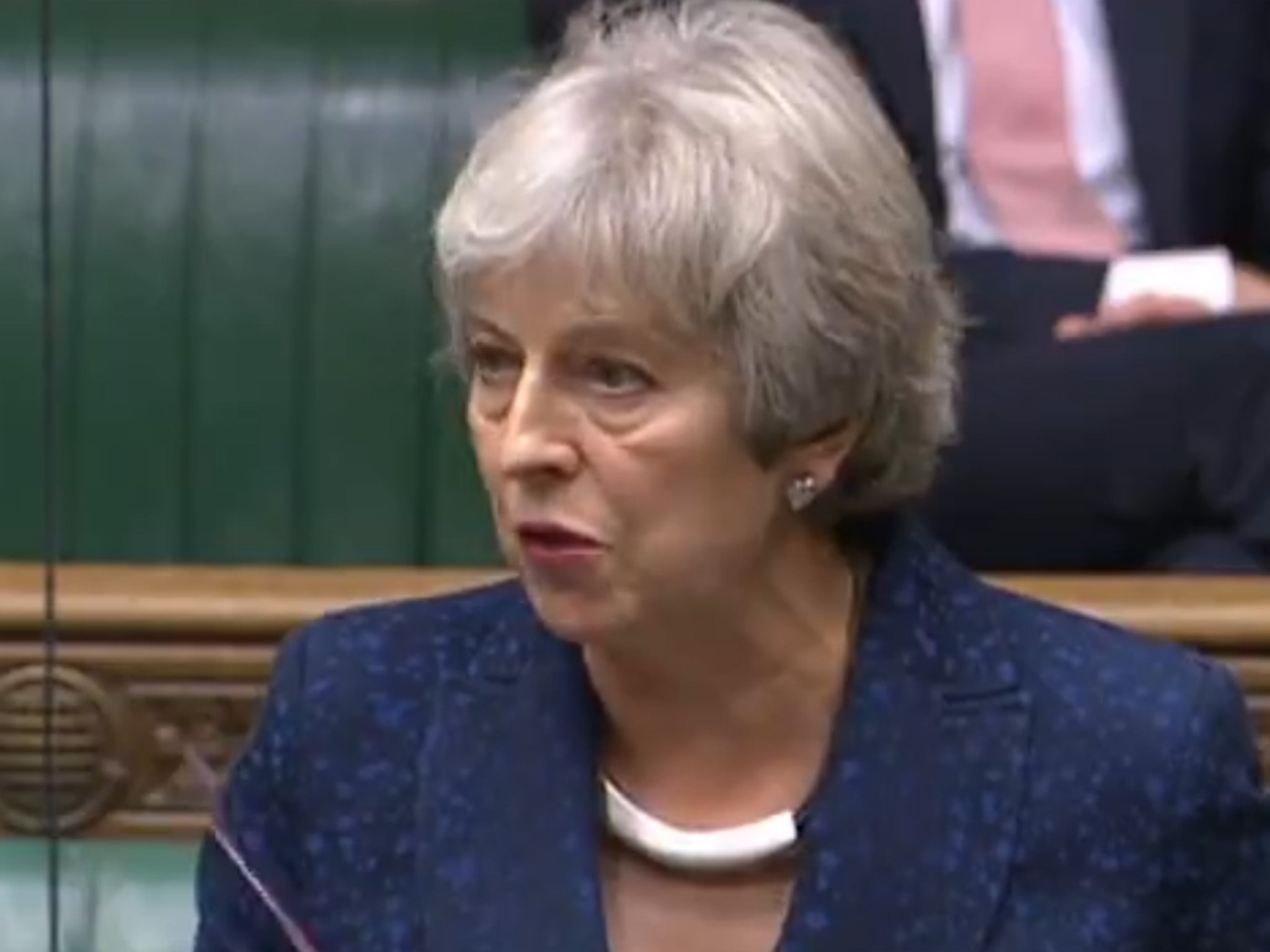

Theresa May refuses to vote with ‘reckless and irresponsible’ Boris Johnson

The controversial UK Internal Market Bill – which gives ministers the power to break international law – completed its passage through the Commons with a majority of 84 and now goes to the Lords, John Rentoul writes

Boris Johnson got his controversial bill through the House of Commons last night, but without the support of his predecessor. Theresa May agrees with all four other living former prime ministers – John Major, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and David Cameron – in opposing Johnson’s policy. As the only one still in the Commons, she had the chance to vote on the matter.

The question on which MPs voted last night was the prime minister’s willingness to tear up the EU withdrawal agreement. The UK Internal Market Bill takes powers for ministers to “disapply” the terms of the withdrawal agreement – that is, to repudiate an international treaty. Many Tory MPs were unhappy about the damage that this would do to Britain’s reputation, but most of them were bought off by a clause written into the bill guaranteeing parliament a further vote before those powers are actually invoked.

But not May. She decided to abstain, having last week made her view absolutely clear that Johnson was acting “recklessly and irresponsibly”.

Thus she leaves Ted Heath as the last former prime minister who actually voted against their own government’s three-line whip. He voted against Margaret Thatcher on the poll tax when it was put to parliament on 18 April 1988 (thanks to Tom Newton-Dunn, Jill Rutter and Philip Cowley for that historical nugget).

But the depth of her disagreement with her successor was unmistakable when she spoke on the bill last week: “I cannot emphasise how concerned I am that a Conservative government is willing to go back on its word, to break an international agreement signed in good faith and to break international law.”

Most of her colleagues were persuaded that Johnson doesn’t really want to break international law, but that he has to threaten to do so in order to persuade the EU side in the trade talks that he is serious – or, as Alok Sharma put it more tactfully last night, that the clauses are a “legal safety net”. He did not add, however, that it is a safety net intended to catch the government in case the EU behaves unreasonably and there isn’t time under the dispute procedure in the withdrawal agreement to put it right. A dispute procedure to which the UK government signed up less than a year ago.

It is not an argument that cut any ice with May. Why would the EU negotiate a new deal with a country that was threatening to tear up an old one? And if it is just a negotiating tactic, won’t the EU see through it?

Enough of the rebels were bought off, however, to send the bill to the House of Lords for the next leg of its legislative journey. There it will make its leisurely progress – the government cannot control the timetable in the upper house in the way that it does in the Commons – as the clock ticks towards 31 December and the expiry of the UK’s membership of the EU single market.

If there is no breakthrough in the EU trade talks soon, then things will get difficult. But last night the prime minister got his way.

One Conservative rebellion in the House of Commons faded away last night; another looks likely to fade away today. Those MPs rallied by Sir Graham Brady, the leader of the Tory backbenchers, to demand votes before new coronavirus laws are expected to back down. They will accept a promise from the prime minister that, of course, he will let parliament have a vote on new rules, if there is time, but everyone must understand that sometimes these decisions have to be taken quickly. What about a vote on new rules in double-quick time after they have come into effect?

It seems that this will be enough for the much-trumpeted rebels. But it is a strange position for Johnson to be in, nine months after winning an election decisively, having to negotiate with opponents in his own party on two fronts.

And May’s opposition ought to sting. Even though she is only one MP, her opposition to the government could be ominous. The issue on which Heath rebelled in 1988, the poll tax, was what brought Thatcher down two and a half years later.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments