Rishi Sunak’s plan to bring Britain back from the brink depends as much on public health as economics

Editorial: The British economy has not known such a grim outlook since the 1970s. The chancellor thinks he can spend his way out of the Covid-19 crisis – but will it work?

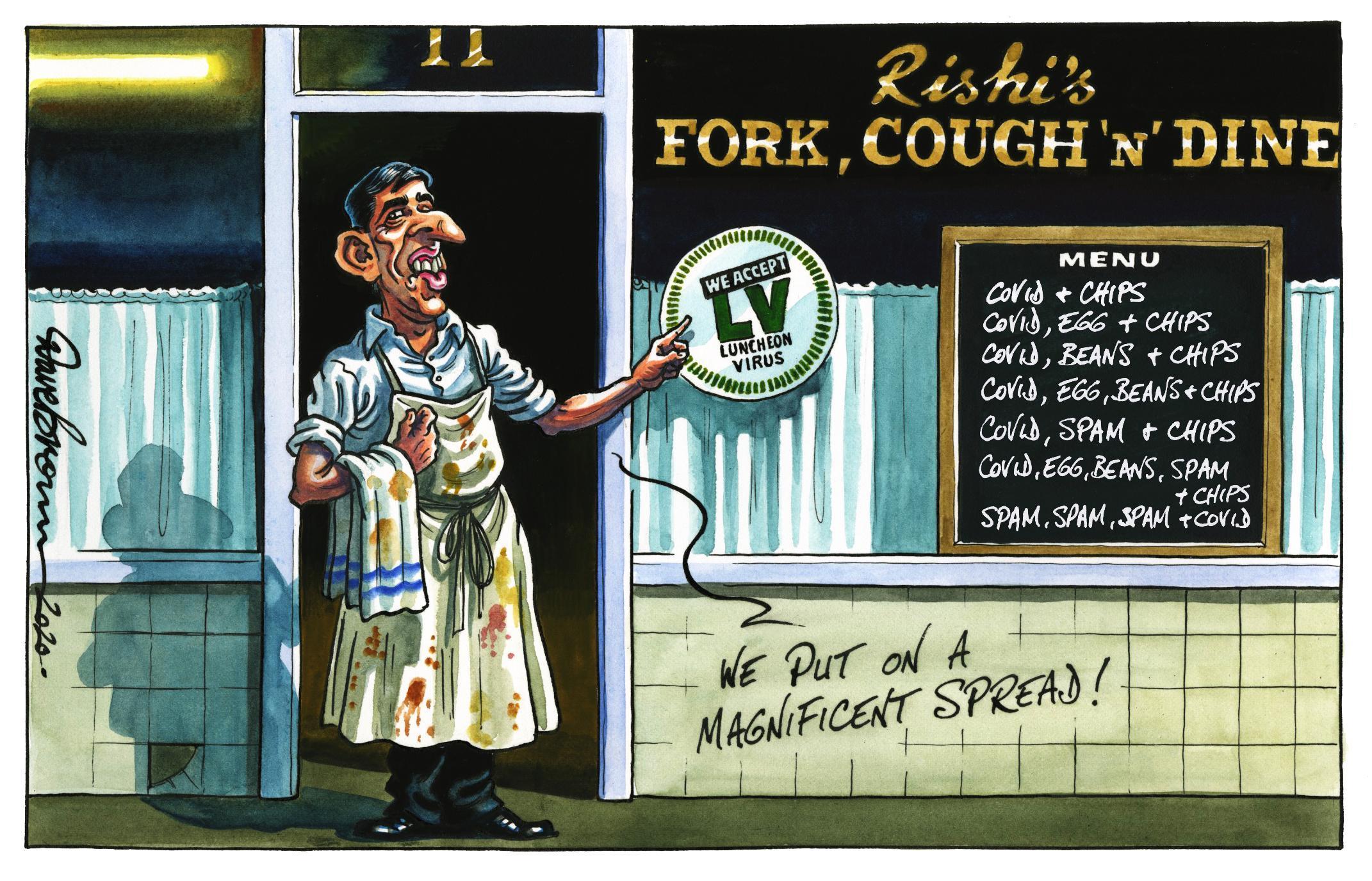

Rishi Sunak is such a charming young man – he’s been called the ideal son-in-law – that he wants to take the whole nation out to dinner. OK, drinks are not included, and there’s a cap of £10, but he’s knocking most of the VAT off, and he is a tee-total chancellor of the exchequer after all.

Sure-footed, polished and creative as Mr Sunak is, though, he’d maybe not spoil a great night out with talk about the country’s economic prospects. These are anything but jolly. The imminent post-Covid, post-Brexit return to mass unemployment, especially among the young, is plainly something that quietly haunts the chancellor. He said in his innocuously named Summer Economic Update (in reality a third emergency mini-budget) that the response to the Covid-19 crisis would “define us”. The winding-down of the jobs retention furlough scheme will be a “difficult moment”. He tried to reassure the public that he does not accept that unemployment is inevitable, another signal that this is no neo-Thatcherite gang of ideologues. The ghost of Sir Keith Joseph is undisturbed.

Recalling, one assumes, the social and economic scars of those who grew up in the 1930s and 1980s, Mr Sunak declares that “we cannot lose this generation”. Ominously and encouragingly in equal measure, Mr Sunak cautioned MPs that this latest £30bn instalment of public spending, job subsidies and tax cuts will not be the last time he will have to boost the economy in the coming months. The underlying commitment to do “whatever it takes” seems to be in place, though the catchphrase was not used. No doubt the same applies to the Bank of England’s financial initiatives.

Will it work? As the shadow chancellor Anneliese Dodds shrewdly pointed out, the answer to that is as much to do with public health as economics. If the government is faced with a second wave of the pandemic, that will mean a second national lockdown – with another huge burden placed on the public finances and on the wider economy. Experience suggests that such a turn of events is perfectly possible, and in Australia and America there are signs of it already. It is no shock that many more billions were committed by Mr Sunak to fresh Covid-19 preparation measures, such as adequate supplies of protective equipment and funding for local authorities: that is suggestive of some nervousness about a winter NHS and care system crisis (and the grim political consequences of a second round of government failures).

The biggest economic reality today is that the cabinet’s premature decision to relax lockdown before infections were lower, and before adequate test and protect systems were in place, risks a second wave of infections. It will cost lives but also place far more stress on an economy already in deep recession. The Covid-19 “bill” would in effect double. It may grow unsustainable.

Apart from that, some of the detailed policies are flawed, and poorly targeted. Most disappointingly, there was yet again nothing on private sector investment, as there has not been through the whole crisis, though it is the key to long term higher productivity and higher wages.

Not all of the £30bn is to be spent wisely. The jobs retention bonus of £1,000 might be easily claimed by businesses who were in any case going to reinstate workers. The “kickstart” scheme for 16- to 24-year-olds will provide low paid work and training for many, but for only a few months. It would take a heroic assumption for future job generation to see them in full-time well-paid employment this time next year. The cut in stamp duty for someone fortunate enough to be purchasing a £500,000 house is hardly needed, and, like similar “holidays” will merely bring forward a decision by the comparatively well-heeled to move to a more comfortable abode; it does nothing for the homeless, for example. As for “Eat Out to Help Out”, a £10 subsidy will not be enough to tempt many nervous older citizens to risk dying in a coma for the sake of a crafty Nando’s. Fear of Covid-19 destroys economic confidence.

The British economy has not known such a grim outlook since the 1970s, and perhaps not since the end of the Second World War. Talk of a V-shaped recovery is all very well, but it may still fall short and be slower than hoped. A second wave would turn it into a W-shaped pattern of recovery – if we’re lucky.

Mr Sunak and his team at the Treasury know very well that, even without a second wave and a second lockdown, the lasting effects of a no-deal Brexit and now of Covid-19 – the “new normal” – could destroy some jobs and businesses forever, unable as they are to cope with the strictures of loss of markets in Europe, and the new rules of hygiene and social distancing.

Indeed, unless an effective vaccine is developed in record time, many aspects of our way of life will not return to normal for years. The economic shock could scarcely be bigger, and it is not over yet. Will Britain be able to borrow and spend its way out of the double trouble of Covid-19 and Brexit? If not, then what? Something for Mr Sunak to discuss over a socially distanced Chequers pub lunch with the prime minister and his chief adviser, maybe.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments