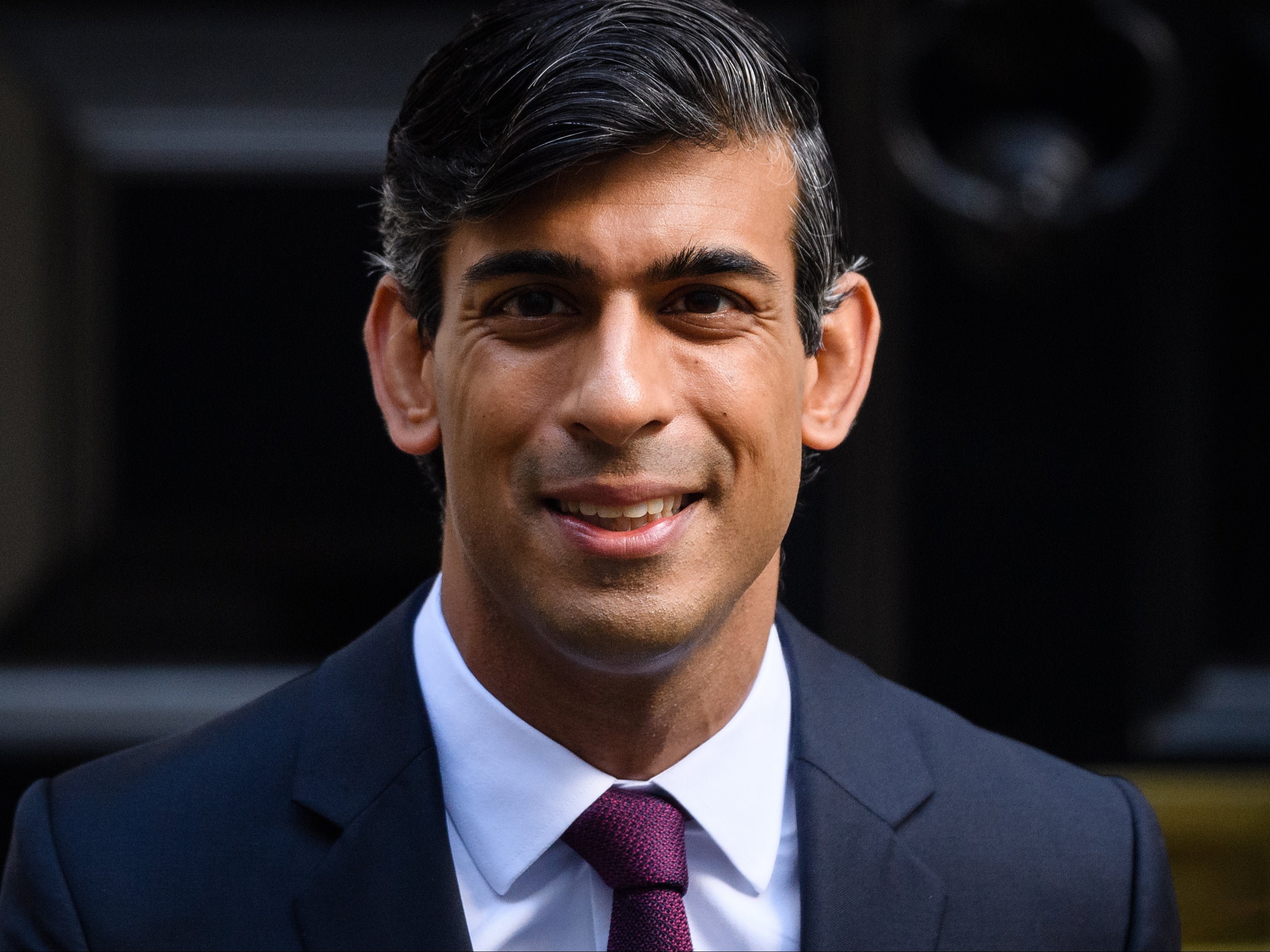

Rishi Sunak’s pitch to be prime minister: competent centrism

The chancellor set out the economic policy not just of the current government, but of the likely next government – his own – writes John Rentoul

Rishi Sunak’s big lecture yesterday was lost in the thunder of war, but it was an important speech to which we should return if we want to understand not just the economic policy of the current government, but the nature of the likely next government.

The chancellor of the exchequer has been losing ground at the bookmakers. On the day a month ago when Dame Cressida Dick, the Metropolitan Police commissioner, announced that she would be investigating alleged lockdown-breaking gatherings in Downing Street, thus postponing the threat of a leadership challenge to Boris Johnson, the betting markets gave Sunak a 38 per cent chance of becoming the next Conservative leader. That shrank gradually to a 26 per cent chance today, as the timetable for a change of leadership receded ever further into the unforeseeable distance.

I think the chances that Sunak will be the next Tory leader and indeed next prime minister are higher than that, because even if Johnson survives until next year, Tory MPs are unlikely to allow him to lead them into the next election. In which case, who else is there?

Unless Liz Truss, Jeremy Hunt, Penny Mordaunt or Sajid Javid can come up with something that answers the seriousness of Sunak’s Mais lecture, that is a question that answers itself. The Mais lecture is traditionally the occasion for the chancellor to set out the big themes of the government’s economic policy. That is what Sunak did, although he had to devote the opening section of the speech to the war in Ukraine – “we are with Ukraine and its people at this difficult time” while “keeping a careful watch on energy markets”.

But because of the speculation about a change of prime minister, and because part of the speech was a defence of the controversial decision to raise taxes that is likely to be an issue in any leadership election, the speech was also a personal manifesto for that leadership campaign. Indeed, it ended by claiming to have set out a “radically different vision of our future economy, built on a new culture of enterprise”. This was intended “not only to deliver prosperity for all our citizens”, which is the chancellor’s job, “but also to advance our values on the world stage”, which is the prime minister’s. “That’s the promise of the free market, and the greater goal of security and human happiness cannot be achieved without it,” Sunak declared, closing with: “That is what I believe.”

So what does our next prime minister believe? First, he believes that he can take on Keir Starmer. The Labour leader was also supposed to be giving a speech yesterday, in Harold Wilson’s home town, Huddersfield. The speech was cancelled because of the invasion of Ukraine, but journalists had already been given extracts, quoting Wilson’s “white heat” of the “scientific revolution” speech of 1963. Sunak referred to a different part of that same speech, in which Wilson quoted Jonathan Swift saying that anyone who increases productivity does a “more essential service to his country than the whole race of politicians put together”.

As the theme of Sunak’s speech was raising productivity, the implication was clear. And Sunak even appeared to have an argument, which is a rare thing to have in a political speech these days – at least, since Tony Blair’s time. “One of the biggest debates in economics right now is about whether innovation is still transformative – or whether it’s part of the ‘great slowing down’,” he said.

“On one side is Professor Robert Gordon, who argues that innovation is no longer happening across the economy in the same way as it did in the 20th century – instead, it’s narrowed to the domains of information, communication, and entertainment.

“On the other side … is Professor Erik Brynjolfsson, another Stanford economist, whose view hinges on the idea that artificial intelligence is a general-purpose technology, like steam power, electricity and information technologies.” Brynjolfsson believes that AI is going to affect almost every industry. “I am an optimist, and I’m with Brynjolfsson,” Sunak said.

But the speech also contained an argument about the politics of economics. The chancellor said he was a firm believer in lower taxes, but went on: “I am disheartened when I hear the flippant claim that ‘tax cuts always pay for themselves’. They do not.”

Flippant? Could that possibly be a reference to Truss, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Lord Frost, who objected to the planned rise in national insurance contributions with the airy suggestions that borrowing should rise instead, or that civil servants who were working from home could be sacked?

Sunak declared: “Cutting tax sustainably requires hard work, prioritisation, and the willingness to make difficult and often unpopular arguments elsewhere. And it is hard to cut taxes at a time when demands on the state are growing.” He pointed out that, even leaving aside the vast cost of the pandemic, an ageing population puts increasing pressure on the NHS and social care.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices newsletter by clicking here

He replied to the people I call punk Thatcherites, who invoke the Thatcher-Lawson years as evidence that lower tax rates always produce higher tax revenues. He quoted Margaret Thatcher and Nigel Lawson explaining why they had to put up taxes to control borrowing before they could afford to cut taxes.

He bracketed them with Labour politicians whose answer to all problems is higher public spending, thus presenting himself as the sensible third way between two extremes: “The trap of both those ideas – that we can simply grow the economy with public spending, or supposedly self-funding tax cuts – is that they are both highly seductive, easy answers. Neither are serious or credible; neither on their own will transform growth; and because they ignore the trade-offs inherent in economic policy, both are irresponsible.”

It takes some intellectual confidence to diss your leadership rivals and the opposition party as unserious, incredible and irresponsible, but his argument is a powerful one not just because it is right, but because it is the winning political formula, the New Labour, Johnsonian third way: fiscal responsibility and decent public services. Only delivered by someone – and this bit wasn’t in the speech – more competent and boasting more personal integrity than the incumbent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments