Libya is still searching for stability a decade after the end of Muammar Gaddafi

A new interim government looking to create a path towards elections marks the latest attempt to unite a country beset by conflict, writes Kim Sengupta

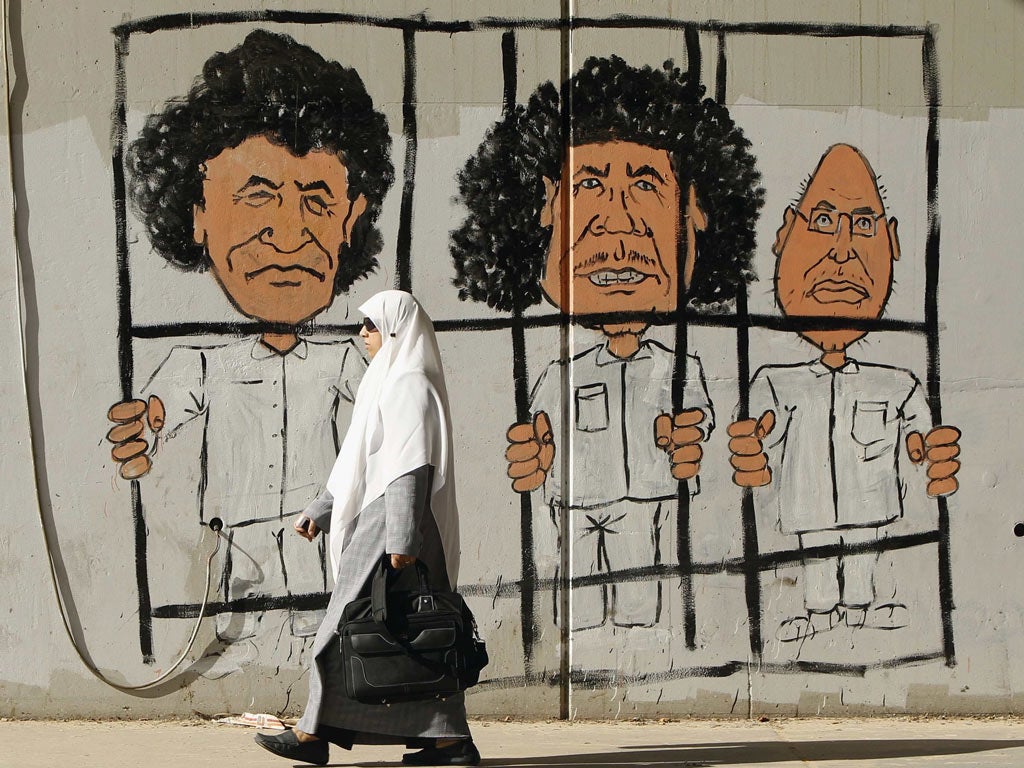

Efforts towards forming a united government in Libya are once again underway, on the tenth anniversary of the revolution which led to the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi amid declarations of a free and democratic future after four decades of dictatorship.

There have been several attempts since then to establish a national administration in the years of strife which followed – and it is not certain that this new one will last until the end of the year when elections are due to take place. But the move has supposedly accepted by the many rival factions.

Dozens of tribal elders, civic society activists, and academics met Mohammed Younes Menfi, the president of the interim administration, in Benghazi at the end of last week to start the process, which will continue with the setting up of a cabinet. Abdul Hamid Dbeibah has been installed as interim prime minister.

There was a strongly held view during the uprising against Gaddafi that the country was better placed than most of the others to emerge from the turbulence of the Arab Spring with stability and cohesion, which would be underpinned by prosperity.

“We only have a population of six million, all not just Sunnis, but Malikis: the communities get on with each other, people aren’t extremists, and we have oil,” Salwa Bugaighis, a lawyer and human rights campaigner told me in Benghazi in the early days of the revolt. “I know oil has been a curse for so many countries, but it will help build civil institutions and empower people here.”

Along with expectations of change, there was wariness about outside influence among the activists of the revolution being hijacked by powers abroad. Posters around Benghazi proclaimed “no foreign intervention, Libyans can do it alone”.

As the regime forces crushed the protests, there was acceptance that Libya may not be able to do it alone, and foreign help was needed rather desperately. It came in the form of a Nato air campaign which was instrumental in the defeat of the regime. But, even then, the suggestion among the opposition was that the future of Libya would be decided by the Libyans themselves, once the fighting ended.

The descent into internecine violence was rapid as heavily armed militias carved out fiefdoms and Islamist extremism began to grow. Some of those who had been leading figures in the early days of the revolution were forced to flee the country. Some were murdered, among them Bugaighis, gunned down at her home on the day of Libya’s second post-Gaddafi election in 2014.

Bugaighis and her husband had taken their son to live in Jordan after an attempt had been made to kidnap him in the past. “She came back to Benghazi to vote in the election, and they killed her the next evening,” her sister Iman told me, “so they were prepared for the opportunity. She had received threats, but she was determined to vote and how could anyone stop her?”

Charges of foreign interference had long been present by then. It was already a hugely contentious issue at the first post-Gaddafi election in 2012. For instance, Abdul Hakim Belhaj, a prominent rebel commander who British intelligence had once helped deliver into the hands of Gaddafi, was accused of being a client of Qatar.

A group of students in Benghazi assured me that Belhaj was so much in Qatar’s pocket that even his campaign colours were the same as those of Qatar Airways. There was, in fact, a definite difference in shades. But his opponents were convinced that they had seen the true colours of the Islamists and were determined to stop him.

Foreign powers arrived in Libya in force over the next few years, with the nation having been split into two centres of political power. One based in the east, backed by General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), and the other in the west – the capital, Tripoli – known as the Government of National Accord (GNA). The Russian private military company, the Wagner Group, is in the country, fighting alongside Haftar’s army (with the Kremlin denying any state involvement with Wagner). As well as Moscow, the former commander in Gaddafi’s army is backed by the UAE, Egypt and France. His main adversary, the UN-recognised GNA, has the support of Italy and Turkey.

The formation of the new interim government took place abroad with a background of manoeuvring by foreign powers. Russia believed that it had an agreement with Turkey and Egypt for the government to be led by interior minister Fathi Bashagha and Aquila Saleh, the chairman of the House of Representatives.

Russian officials hold that the emergence instead of Menfi and Dbeidah as leaders was manipulated by the US. it is believed, however, that Moscow does not want to challenge the administration of president Joe Biden over the issue. It is prepared to wait and see whether the latest political road map will flounder like so many others have done in the country. In any event, judging by the flurry of visits to Moscow by Libyan politicians, Russia will be well represented in the interim cabinet.

Haftar has met interim president Menfi and wanted to publicly give his backing for the peace process. The former officer in Gaddafi’s army was once seen as the emerging leader of Libya, thus following in the pattern of strongmen back in power in Arab Spring states, such as president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi Egypt.

But Haftar’s fortune has waned somewhat after he failed to capture the capital, Tripoli, in a much-publicised offensive two years ago – accompanied in the subsequent loss of a swathe of territory. Haftar supposedly wanted to launch another offensive, this time against the port city of Misrata, but this was firmly quashed by Moscow.

The Gaddafi family, meanwhile, are scattered around north Africa and the Middle East. Saif al-Gaddafi, the son who was seen as the colonel’s heir, was captured in the aftermath of the revolution by rebels who allegedly cut off the two fingers with which he used to give victory salutes. Saif was released from prison in Zintan in 2017. The Zintani authorities refused to transfer him to the custody of the International Criminal Court in Hague, which has a warrant out for his arrest.

Saif al-Gaddafi has announced that he would run for the presidency. Leaked documents allegedly showed that Russia’s Wagner Group was actively promoting him. It had presented him with a PowerPoint proposal for strategy and restarted Jamahiriya TV, a channel which was used to disseminate his father’s view of the world, and had moved to Cairo from where it had been broadcasting intermittently.

The company also set up a dozen Facebook groups promoting Saif and Haftar. The leaked papers were critical, however, of Saif Gaddafi as well, claiming that he had “a flawed conception of his own significance”, and needed to be diligently monitored for any project to work.

There have been reports of Saif meeting Egyptian officials in Cairo. He had frequently praised President Sisi for “saving his country”. He has also repeatedly thanked Saudi Arabia for its “constructive” role in Libya.

Whether cultivating international support leads to the son of Muammar Gaddafi attempting to gain power remains to be seen: but the consequences of all that has unfolded from the 17 February revolution are still being played out in Libya.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments