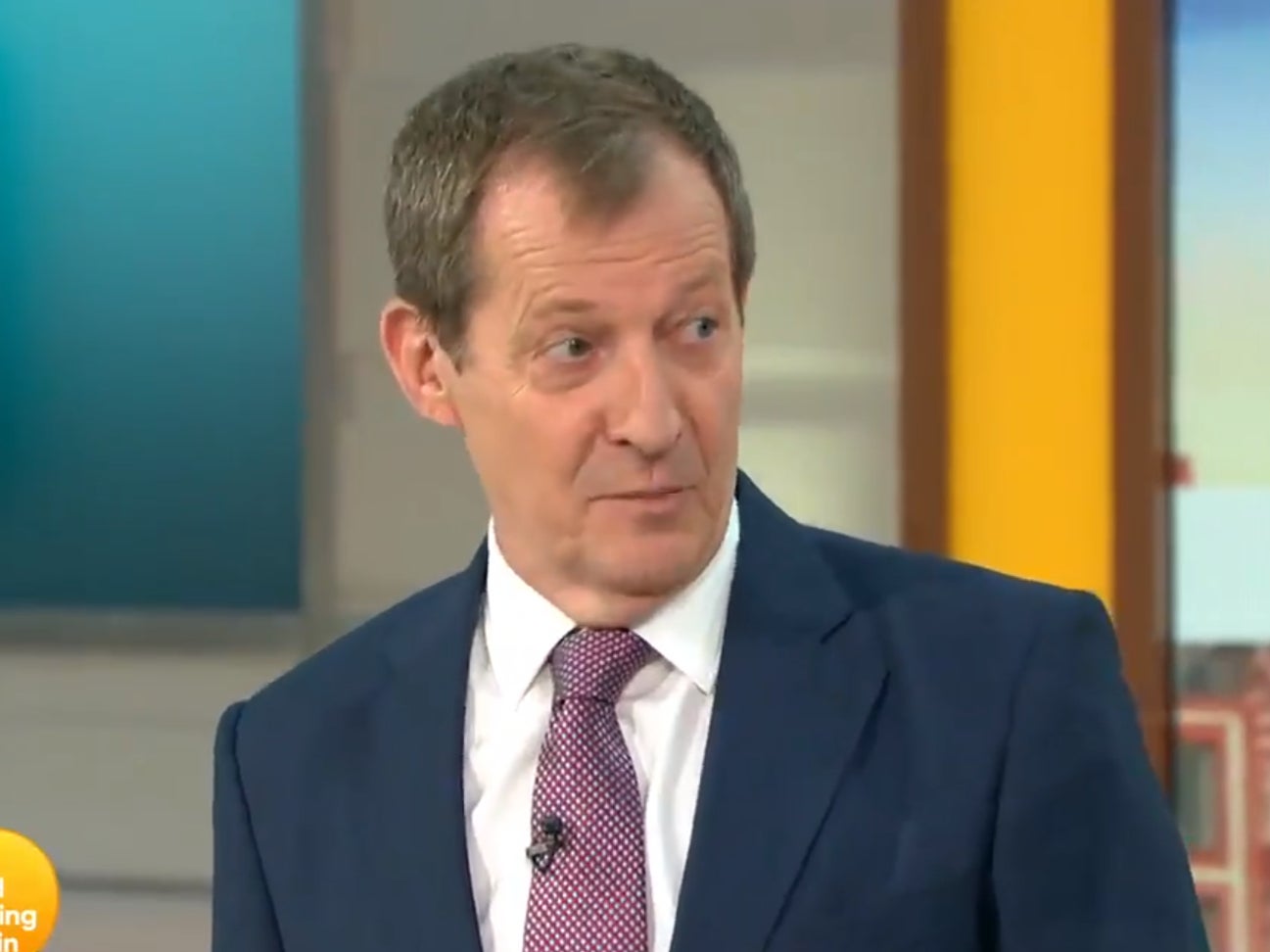

The ‘how not to do it’ guide for Keir Starmer from Alastair Campbell

The latest volume from New Labour’s foremost diarist offers lessons from recent history for today’s Labour Party, writes John Rentoul

The two big stories of the latest volume of Alastair Campbell’s diaries are connected. He tries to sum up the period between the elections of 2010 and 2015 as “the rise and fall of the Olympic spirit” – the London Games being a great legacy of the New Labour years. But the real stories are Ed Miliband’s leadership and Campbell’s own angst about whether to stand as an MP himself.

So the diaries start with the election of the wrong brother as Labour leader, and end with his failure in the general election five years later – with Campbell’s decision not to enter politics in the middle.

Campbell was clear in private that Ed Miliband’s election was a “disaster”. He wrote: “The wrong choice in the wrong way.” But he was such a Labour loyalist that his public comments were muted, and he spent the next five years as a semi-detached adviser to the leader.

Campbell was a critical friend, recognising that Miliband had some qualities. He was resilient, even-tempered and worked to improve his communication skills. Miliband repeatedly tried to persuade Campbell to work for him full time; Campbell repeatedly tried to get Miliband to stop trashing the New Labour economic record. They each succeeded in resisting the other.

The question that hangs over the whole period is what would have happened if David Miliband had fought a better campaign; if he had persuaded just six MPs to back him rather than his brother.

It is not obvious that the end result would have been different, but the party would have taken a different route to get there. David Miliband would have suffered from the Iraq mania that had gripped the party. The growing spasm that eventually propelled Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership would have torn the party apart – instead Ed Miliband smothered it, “making the party feel OK about losing”, as Campbell put it.

If David Miliband would have had a problem holding the party together, though, it would have been worse for Campbell if he had tried to become leader. He thought that was a possibility. It presumably wasn’t what Ed Miliband had in mind when he urged him to look for a seat and to try for a by-election, but others including Charlie Falconer, the former justice secretary, told Campbell he “would be straight into a top job”, and Tony Blair asked him: “Do you want to be leader of the Labour Party?”

The emotional centre of this volume is the period in the second half of 2012 and early 2013 when Campbell thought about it and decided against. In a powerful passage he “thinks in ink”, explaining the pressure it would put on his family and therefore his own mental wellbeing. One of the subplots of these diaries is his son Calum’s struggle with alcohol, and he recounts with unflinching honesty Calum’s resentment at his father’s absence during the Blair government years.

Having decided against trying to lead the party himself, and having established that Alan Johnson, the former home secretary, was not interested in trying to replace Ed Miliband, Campbell had to make do with the flawed leader the party already had. He carried on advising him, still urging Ed Miliband to avoid stoking the Conservative line that the last Labour government had wrecked the economy, while Miliband still insisted he had to be the candidate of change.

As the 2015 election approached, Campbell allowed himself to be swayed by the opinion polls and the optimism of Miliband’s team. He also thought, as he played David Cameron in the rehearsals for TV debates, that Miliband was getting better. (The American advisers imported by Miliband were shocked by how brutal Campbell-as-Cameron was, criticising him for betraying his brother.)

But Miliband ended up adrift, buffeted by the Conservative charge of preparing to rely on Nicola Sturgeon to form a minority government. Which was true: Campbell, Falconer and many of Miliband’s inner team were working on hung-parliament scenarios that assumed the SNP would not stand in the way of Miliband becoming prime minister, because the only alternative would be a continued Tory government.

Indeed, some of the behind-the-scenes planning went further. Campbell recounts approaches from Alex Salmond, who had stood down as first minister of Scotland and who was preparing to re-enter the House of Commons, about his being deputy prime minister in a Miliband government.

Miliband took fright at the Tory attacks on the “coalition of chaos”, and took a harder line with the Scottish National Party than Campbell advised, ruling out any form of co-operation. But the damage was done and the ground had not been prepared.

Which brings us to the present day. A lot has happened since 2015, and yet the run up to the next election could be similar to the period covered by these diaries. Keir Starmer leads a weak team (Miliband’s shadow cabinet was “invisible”, Campbell often complained), and his best prospect of becoming prime minister is as leader of a minority government in a hung parliament – a Labour majority government would require a bigger swing even than Blair’s in 1997.

Starmer’s team could do worse than to study this volume carefully, to understand how to forestall the inevitable speculation about having to deal with the SNP, and how to avoid being led by the nose by opinion polls.

‘Alastair Campbell, Diaries: Volume 8, 2010-15, Rise and Fall of the Olympic Spirit’ is published by Biteback, £25. Reviews of previous volumes are linked here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments