Bullies don’t deserve high office – so why give peerages to John Bercow and Karie Murphy, both of whom have been accused of as much?

The nomination for peerages of Karie Murphy and John Bercow is a symptom of a system that prioritises nepotism over the health of our democracy, writes Frances Weetman

Democracies are tested in periods of chaos. It isn’t hard to make the case that western liberal democracy is facing a period of unprecedented unrest. In the last week alone, the US has seen impeachment proceedings against Donald Trump thrown out by a Republican-controlled Senate, while the UK’s departure from the European Union has raised many questions about the country’s future. In both cases, the infrastructure of our democracies – their processes, conventions, shortfalls – have become exposed, and tested to their limits.

The last five years have seen the British political landscape shift so dramatically that our parliament is barely recognisable as one that belongs to one of the west’s oldest democracies. Sure, British MPs work in a building that has existed in part since 1097, but the last year of parliamentary chaos has many thinking (rightly or wrongly) our elected representatives are barely distinguishable from a rabble being forced out of a pub after last orders.

It is with this backdrop that our democracy’s shortcomings are laid bare. Conventions and unwritten norms are tested to their limits. And in no arena has this been so grotesquely transparent as in the House of Lords nominations, published in January.

The house itself divides opinion. Many make the argument that it should be replaced with an elected chamber, equivalent to the US Senate. Its system of life peerages, in which a person can be granted a job for life via political appointment, is rooted in cronyism and the self-congratulation of the political establishment. It is routine, for example, for outgoing prime ministers to nominate their aides and allies for Lords membership. In theory, however, the Lords’ purpose is to provide expertise and sober deliberation to counterbalance the Commons’ (relatively) youthful enthusiasm.

This system depends on a great deal of trust in those nominating. It would normally go without saying that individuals facing serious bullying allegations would not be deemed suitable to play such a crucial role in our democracy. But these are clearly not normal times.

While appointments to the Lords are inevitably political, it is usually easy to justify them: take the examples of Labour politician Peter Mandelson and former Theresa May chief-of-staff Gavin Barwell. Both polarise popular opinion, but each has extensive experience in shaping government and policy – useful skill sets in the Lords.

The same cannot be said for Karie Murphy, executive director of the leader of the opposition’s office. Labour’s electoral success during the period Murphy served isn’t exactly worth framing on the family mantelpiece. That alone should not necessarily preclude her from high office – but presiding over a seemingly bullying and toxic working environment should.

Following her nomination, multiple former Labour staffers came forward with serious allegations of bullying and harassment. These include pinning staff against a wall; falsely telling colleagues that specific workers had mental health problems; and disclosing a colleague’s miscarriage without permission (all of which Murphy denies). Murphy’s role in Labour’s antisemitism crisis is still open to question, and will continue to be until the conclusion of the Equality and Human Right Commission report later this year. But it is impossible to overlook the fact that her time in the leader’s office saw multiple staffers resign over alleged institutional antisemitism, with one reporting to the BBC he experienced suicidal thoughts due to the toxicity of the working environment. At least one staffer who decided to blow the whistle on Labour antisemitism faced threats of legal action issued from Carter-Ruck on behalf of the party. That doesn’t exactly seem like a healthy working environment. It naturally raises the question as to whether Murphy’s appointment would negatively impact the work of the Lords.

Of course, it would be easy to view Karie Murphy’s nomination in isolation – an anomaly and a single, extreme case in an antiquated system that was already rife with problems. That is, until you consider the nomination of John Bercow.

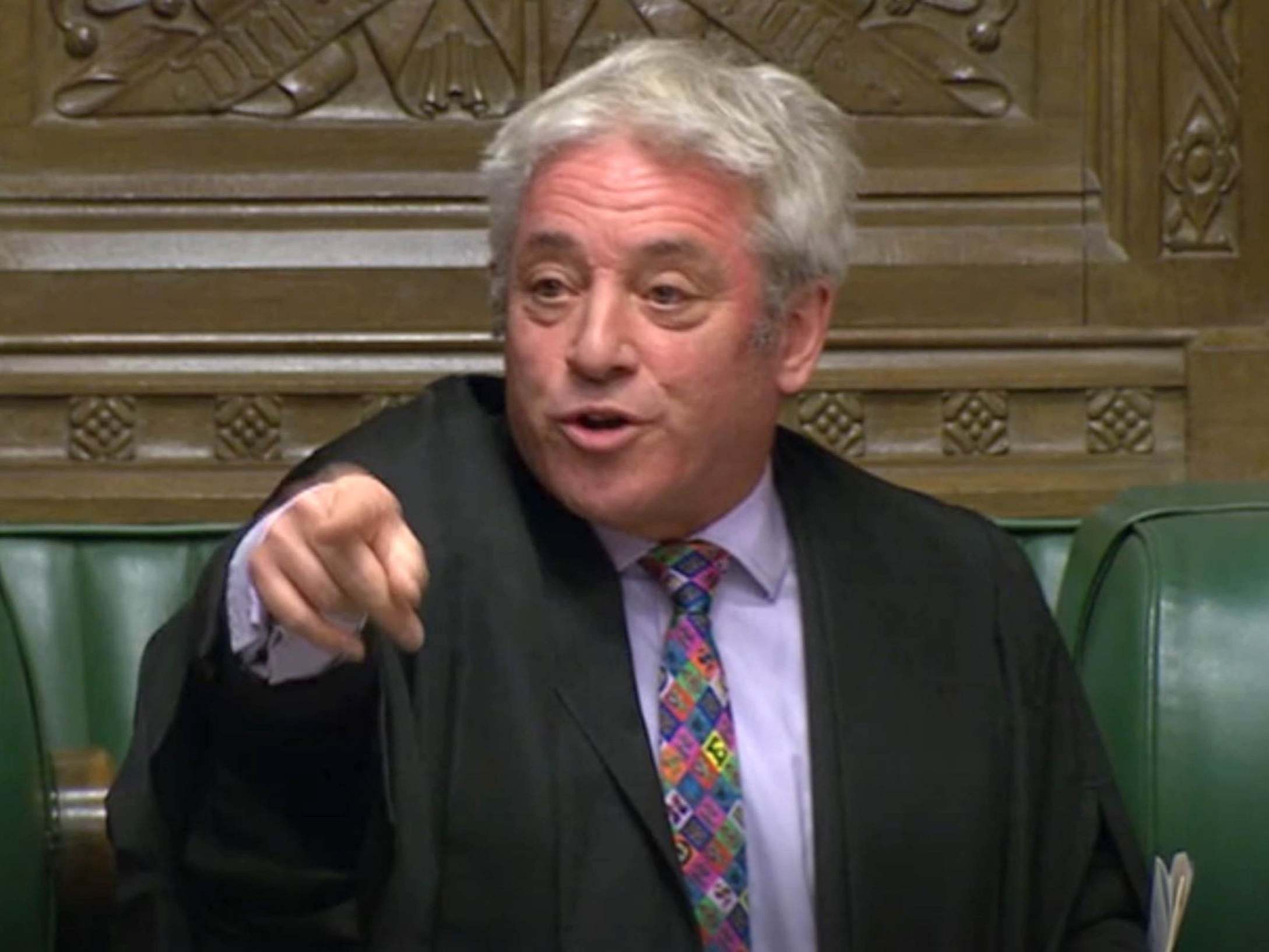

In nominating the former Conservative MP, the Labour leadership has taken the unprecedented step of breaking with tradition, which normally dictates parties nominate only from their own crop of politicians. Bercow’s tenure as speaker of the Commons wasn’t without controversy, but it’s easy to make the case he is experienced in the internal politicking that will be invaluable when working in the Lords. What is not so easy to justify is his nomination when he, too, is facing a raft of bullying allegations of his own (which he too denies). His nomination seems to form part of a trend where bullying allegations are ignored by the Labour leadership. At the very least, bullying allegations are not a deal-breaker.

In nominating two individuals facing serious bullying accusations, the Labour Party has shown that it values nepotism over the values it was originally designed to uphold: the representation of workers over their bosses, promotion of a society that hands power to the underdog from the well-connected and powerful, and the advancement of fair treatment in the workplace. More importantly, these nominations show the Labour leadership’s willingness to violate the good faith usually seen in Lords’ appointments.

What these nominations signal for our broader democracy extends beyond the Labour Party. They represent more than a simple departure from business-as-usual. They are symptoms of a system that, in difficult times, has prioritised nepotism, and a preference for brute force and power in the workplace, over any desire to improve the country or the standard of its democratic debate.

Once a system has become debased, it is overwhelmingly difficult to go back. It sets a precedent that may well influence future decisions. In isolation, the nominations may not seem like a historic event. But the erosion of democratic values never happens overnight. It begins with small, gradual changes that move the common standards of acceptable behaviour within a political system. If these changes continue unchecked, democracy weakens.

These things may start small, but they risk culminating in the normalisation of bullying and hatred. The UK should not give hate that chance to thrive. Chaos is sometimes inevitable. Caving to bullying is not.

Frances Weetman is an independent councillor for North Tyneside

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments