Keir Starmer has no excuses for the scale of the defeat in Hartlepool

The Labour Party’s first reaction has been to resume its civil war – but neither side has the answers, writes John Rentoul

When Keir Starmer said that Labour had a mountain to climb, we didn’t think he would start by heading off downhill. If he had chosen a better candidate in Hartlepool, he could possibly have made the case that the by-election there was always going to be a tough fight because the Brexit Party had split the vote at the general election.

But the result in Hartlepool was far worse than that. Paul Williams, Labour’s strong Remainer candidate, lost vote share, and the results from the rest of the country also suggest the party is going backwards.

It may be that later results from London and the south of England will be better for Labour, but the early indications are that it won’t be anything like enough to compensate for the losses in working-class areas that voted to leave the EU in the referendum.

The crumbling red wall is not confined to the north of England and the Midlands. Labour has lost control of Harlow council and lost seats in other Essex councils. The disaster of the general election is being repeated in these elections across England. While Leave voters have united behind Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, Remainers are lukewarm about Labour, with a tendency to drift off to the Greens and the Liberal Democrats.

The immediate Labour response has been to restart the civil war, with Jeremy Corbyn supporters saying that they cannot be blamed this time, and Starmer’s supporters saying oh yes they can. The message from Starmer is that he inherited the worst Labour defeat since the war and that he cannot be expected to turn it around in 13 months.

Neither argument is compelling. Corbyn did a great deal of damage to Labour’s reputation, but Starmer has made mistakes in trying to repair it. Caroline Flint, the Labour MP who lost her seat in the general election, and no Corbynite, pointed out that “in the past few weeks Labour has been obsessed with curtains in Downing Street” and that has not been cutting through to people.

What is striking about the Labour response, however, is that the Corbynites don’t have an answer. Diane Abbott said Labour held Hartlepool at both of Corbyn’s general elections – neither of which resulted in the election of a Labour government. Richard Burgon said Labour’s manifestos in 2017 and 2019 were “backed by a large majority of voters” – although not by actually voting for them. And Lloyd Russell-Moyle sarcastically observed that it was “good to see valueless flag waving and suit wearing working so well”.

Yet no one has suggested that a different leader could have done better, which points to a more fundamental problem for the party. What these results show clearly is that Brexit was not a one-off disruption to politics, but an accelerator for deeper changes. The Conservatives are increasingly the party of the working class, while Labour is becoming the middle-class party. The growth of higher education has produced more and more liberal professional graduates, who now make up the core of Labour’s support.

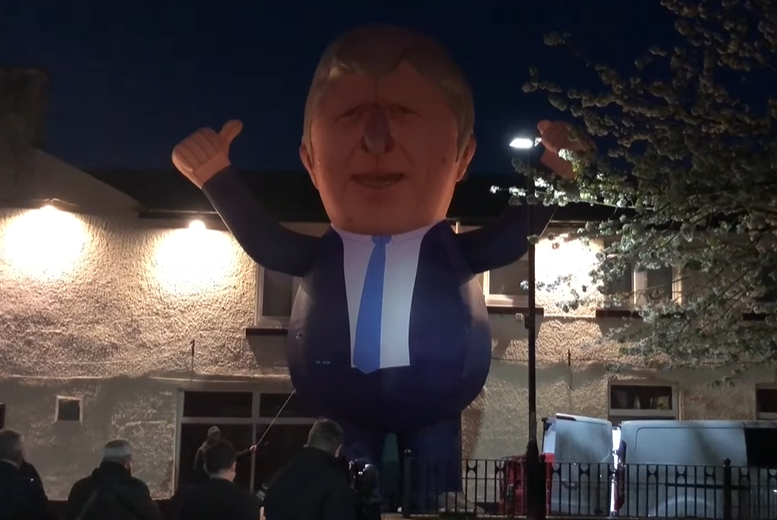

There is no reason this trend should damage Labour, because the graduate jobs are growing and the manual working class is shrinking, but the Conservative Party has managed the cultural contradictions thrown up by this shift better than Labour has. Boris Johnson is popular with Leave voters but has retained enough of the support of Tory Remainers to give him a solid electoral base, while Starmer has been unable to pull off the trick of uniting the opposite coalition.

If Labour had chosen a Leave supporter who lived in Hartlepool as its candidate – and the strong third place for Sam Lee, a former sports journalist who ran as an independent, showed the pull of localism – a close defeat could have been presented as turning the corner. Starmer’s supporters could have put these election results down to the success of the vaccines and waited for more favourable political circumstances around the corner.

But the scale of the crushing defeat in Hartlepool, and the failure to make any progress in any Leave-voting areas, suggests that Labour’s problems won’t be solved by just waiting and hoping.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments