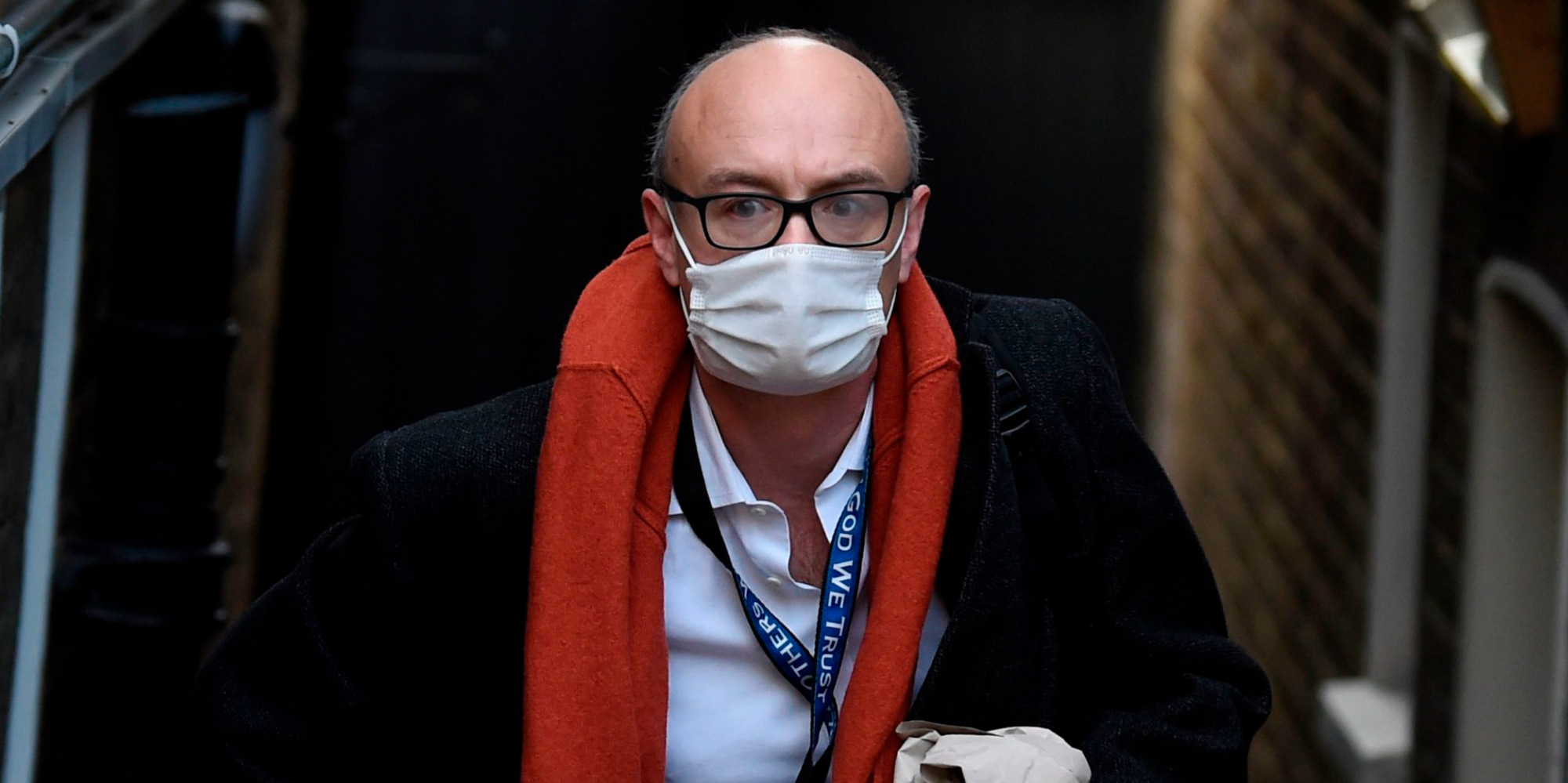

The sunshine has returned to Whitehall following the departure of Dominic Cummings

The more conciliatory tone reflects a belated recognition in Downing Street that successful reform in Whitehall cannot be imposed from the top but must win buy-in from the staff affected, writes Andrew Grice

The dramatic departure of Dominic Cummings, who warned that a “hard rain” was about to fall on the civil service, has been followed by a glimpse of winter sunshine in Whitehall. Although ministers insist they will press on with reform, Whitehall insiders tell me the “tide has turned” against the macho, confrontational approach favoured by Cummings, who was Boris Johnson’s closest aide. Instead of smashing the crockery to see where the pieces landed, as the great disruptor Cummings wanted, politicians are finally trying to take Whitehall officials with them. About time, too.

Cabinet ministers are also pushing back against the “command and control” Downing Street operation, favoured since Johnson became prime minister. Ministers and officials joined forces to oppose a plan to axe up to 3,000 civil service press officers in government departments and concentrate power in the Cabinet Office. It was proposed by Lee Cain, a close Cummings ally since their days in the 2016 Vote Leave campaign, who left his role as No 10’s director of communications the day before Cummings departed three weeks ago.

Cain wanted to limit each department’s communications team to around 30 officials – the big ones have about 200 – and see them employed by a stronger central unit in the Cabinet Office. It caused consternation among press officers who, typically, had not been forewarned they might lose their jobs, as they worked round the clock to help ministers in the coronavirus crisis, and who had to live with a cloud over their heads for five months.

I’m told that Alex Aiken, a former head of the Conservative Party press office, who is now executive director for government communications, lost trust and credibility in the eyes of many departmental comms officials for not resisting what they saw as an attempt to politicise a politically neutral machine. Insiders say he retains the support of key Downing Street players, as well as Johnson.

The shake-up was due to be announced last month but was quietly shelved. Although the chancellor Rishi Sunak’s spending review referenced reform to “unify government communications” under one operating model, ministers and their top officials successfully resisted the plans. Aiken has promised communications staff there will not be “any significant changes to headcount until at least the second half of next year”, and these would depend on the new model created with “colleagues”. Compulsory redundancies are now unlikely.

The more conciliatory tone reflects a belated recognition in Downing Street that successful reform in Whitehall cannot be imposed from the top but must win buy-in from the staff affected. Dan Rosenfield, a former Treasury official who will start work as Johnson’s chief of staff on Monday, is seen as some who will build bridges with Whitehall rather than a believer in creative destruction like Cummings.

The proposed comms shake-up damaged morale. So did Johnson’s refusal to sack the home secretary Priti Patel even though an official inquiry into bullying allegations found she had breached the ministerial code.

There is a strong case for civil service reform. The state has hardly covered itself in glory during the coronavirus crisis. Yet Johnson and his ministers often rush through change to protect their own backs by blaming officials and bodies such as Public Health England, which is being axed. The head of the regulator Ofqual resigned over the exam grades fiasco, but Gavin Williamson remains education secretary. His permanent secretary was one of four forced out under the Cummings revolution, along with Mark Sedwill, the cabinet secretary.

The reforms should address the high turnover in departments and the huge cost to taxpayers of firing and rehiring officials and relying on outside consultants. Theodore Agnew, the Tory peer and Cabinet Office minister working on reforms with Michael Gove, is said to be shocked by the scale of consultants needed to plug gaps in the Whitehall machine.

Ministers should also look in their own backyard. Handing lucrative coronavirus contracts to people known to Tories without the usual bidding process is a scandal that must end. The National Audit Office spending watchdog disclosed last month that hundreds of firms were put in a secret “high priority” channel after their names were passed on by ministers and MPs as £18bn of contracts were awarded by July. We probably don't know the half of it. Indeed, the source of more than half of such recommendations has not been disclosed.

Whatever the admittedly huge pressures during an unprecedented crisis, corners cannot be cut in this way. The system cannot be run on the basis of “who you know, not what you know”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments