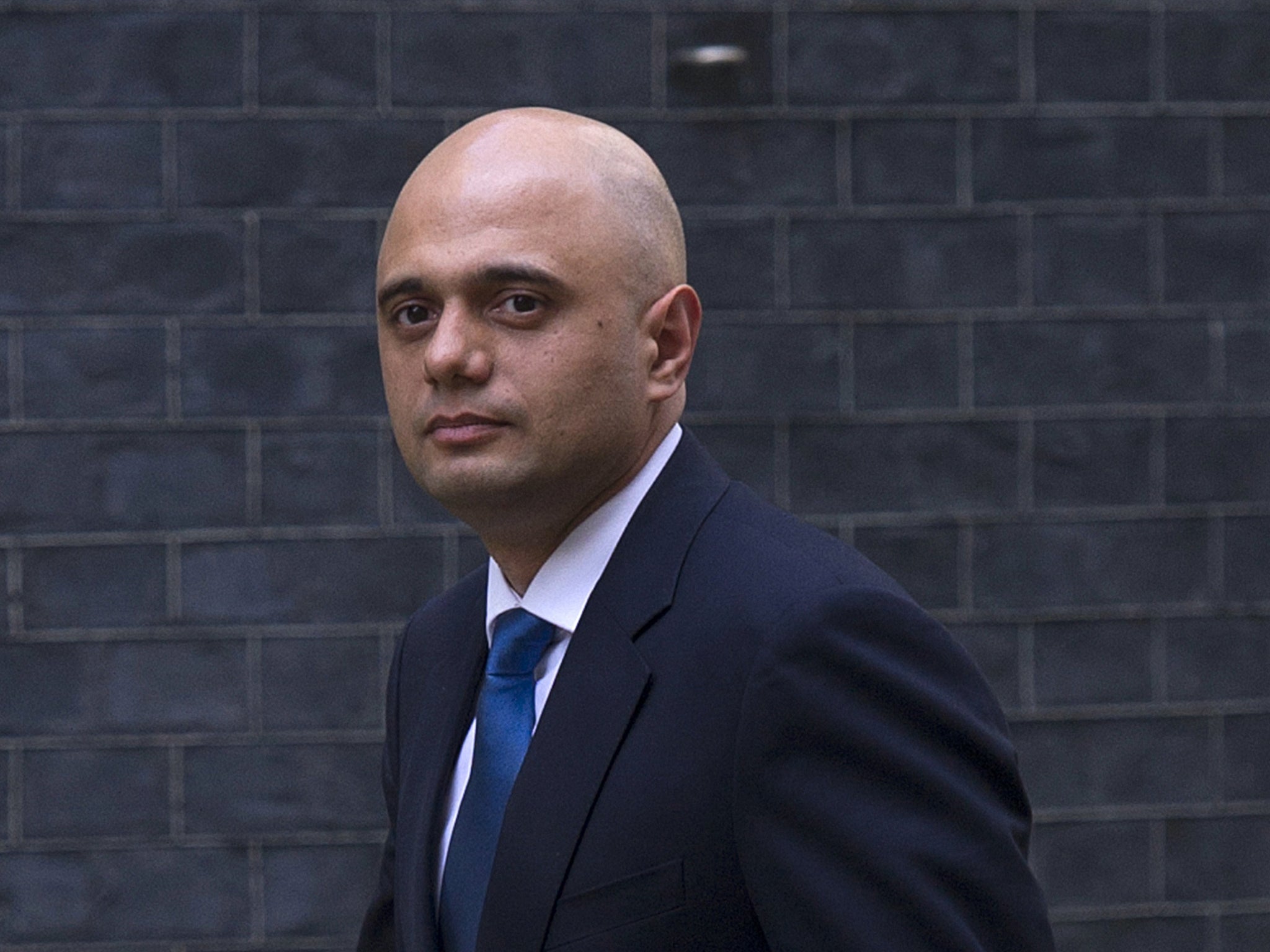

Lessons learned by Sajid Javid from his rapid rise – with less said about his sudden fall

‘It’ll be yours one day’: George Osborne showed his ‘apprentice’ the chancellor’s flat in Downing Street – and it was, but not for long, writes John Rentoul

Sajid Javid, the recent chancellor of the exchequer, came to King’s College London yesterday to speak to the class on the Treasury and postwar economic history run by my colleague Jon Davis.

The postgraduate class is the jewel in the crown of the Strand Group at King’s, which includes the Blair Years course that I co-teach, and it has attracted a large number of serving Treasury officials, keen to learn about – and from – their department’s history.

The class met online, with Davis joined by Ed Balls, a new professor at King’s, and Nick Macpherson, who was permanent secretary at the Treasury until 2016. It was a masterclass in how the relationship between ministers and civil servants works in practice.

Javid started with a self-deprecating introduction, saying that he would make his comments “proportionate to the time that I’ve spent in office; when you had Gordon Brown he spoke for about an hour, so I think I’m done”.

Fortunately he continued, saying drily that he had gone into politics after 19 years in investment banking, “because I was determined to have a career that had a better reputation in the eyes of the great British public”. (That was at the time of the MPs’ expenses scandal in 2009.)

Elected MP for Bromsgrove in 2010, he was an early rising star of the coalition government, appointed by George Osborne as his parliamentary private secretary (PPS) – “I felt I became a bit like his apprentice”. In this first role as Osborne’s “eyes and ears” in the House of Commons, he had to deliver some documents to his boss in the flat above 10 Downing Street that the chancellor has occupied since Brown’s time. Javid remarked on how lovely the flat was. “Do you like it?” asked Osborne. “Yes,” said Javid. “It’ll be yours one day, so I’m glad you do.”

In 2012 Javid became a junior minister at the Treasury – economic secretary – and he gave the class a case study in the relationship between a minister and civil servants. There was nothing self-deprecating about this tale. He had been asked by Osborne to work on making London the western capital of Islamic finance. As a banker he had traded sukuk bonds – a way of borrowing that is compliant with the Islamic prohibition of usury – so he was familiar with the idea and set about planning for the government to issue them.

Treasury officials told him: “You can do an Islamic bond, but the problem you’ll have is that it will be more expensive, so the taxpayer is going to have to end up paying for this and therefore we don’t recommend you doing it.”

Javid said: “I learned that I wasn’t the only minister that had asked for this advice. In the past, Gordon Brown had asked for it, Alistair Darling had asked for it; they always got the same advice and were always being put off by this view of the Treasury. The only difference this time was that I had worked in the markets and I had traded Islamic bonds, and I just did not accept this advice.” He recounted how he had gone to Nick Macpherson, the senior civil servant in the Treasury at the time, who said he wouldn’t stand in his way if he sought to persuade the chancellor. Osborne was duly persuaded, “the bond was done a few months later, and it was below price as I said it would be, for the reasons that I said it would be”.

He said the lesson of that episode was that, despite Treasury officials being dedicated professionals and academically very strong, “sometimes there’s a lack of experience from the business world” – although he qualified it by saying, “It has improved; it has changed.”

His other main point for the class was to say that one of the relationships often underestimated by civil servants is that between a minister and fellow MPs. “In every secretary of state job I’ve had, every ministerial job I’ve had, many civil servants don’t quite understand that you have another job. You may be the chancellor, but you are also a member of parliament.

“That is a vital relationship, and so many times I had, in my diary, surgery meetings in the House of Commons tea room with fellow MPs, or in the chancellor’s office, but they would often just get taken out by a diary secretary because they were seen as disposable. But not enough civil servants have understood that there’s a constituency in parliament that ministers need to look after. And if they don’t, their job gets harder, especially if you haven’t got a big majority – on legislation, on amendments, on troublemaking in the press.”

By happy coincidence, for an ex-minister who is hoping to return to cabinet, this involved rehearsing his ministerial career, as the only chancellor except Winston Churchill – “I’m happy to be second to Churchill” – to have been secretary of state of four different spending departments. In Javid’s case he was at culture, media and sport, at business, at housing and local government, and at the home office before Boris Johnson appointed him chancellor in July last year.

Finally, he said there was one more group of MPs to whom he paid attention as chancellor – and that was the opposition, in particular the shadow chancellor and the Labour leadership. He paid Professor Balls the compliment of saying that Osborne, the Treasury special advisers and he, Javid, would watch Balls as shadow chancellor when he delivered conference speeches, because they respected him – “and if he came up with a good policy, we’d pinch it”. When it came to John McDonnell, however, “the credibility just wasn’t there – this is not a personal thing; I liked the man and I had a lot of respect for him, but the credibility was lacking.”

In answer to questions from the class, Javid gave another example of how activist ministers need to keep pressing to get the civil service to deliver: “When I was home secretary I banned the political wing of Hezbollah. The whole Treasury machine said don’t do it, the foreign office, DfID [the Department for International Development], because it will be a disaster; it actually worked out fine. When I got to the Treasury, in my box is this regular thing that comes up every year, and it is the sign-off on the asset freezes on terrorist organisations. And I looked at it, and I looked at Hezbollah, and it was still only the military wing, not the whole organisation. So I called the officials in and said, ‘I want to speak to someone who knows about this,’ and, to cut a long story short, it took ages to get the Treasury machine just to agree that we should be consistent as a government. Their view was that we’ve always done it this way; it has never caused us a problem before and anyway the political wing probably hasn’t got any assets in the UK. But that’s not the point.”

Professor Balls tried to encourage Javid to talk about the circumstances of his resignation, in February this year, by asking whether – with a backward look to Tony Blair and Gordon Brown – “a bit of tension and grit” in the relationship between a prime minister and a chancellor might be a good thing: “Is it right to say that if No 10 wants to run the Treasury, that’s normally neither in the interest of the government or No 10?”

Javid agreed that the relationship between prime minister and chancellor is the most crucial in government, but refused to be drawn further. “My relationship with the prime minister was very good and remains very good. That doesn’t mean to say there aren’t challenges sometimes in other aspects of the relationship; you do tempt me to talk about it, but you know what, I’m going to resist it.”

He did however defend the close relationship between David Cameron and Osborne, in contrast with what Balls tried to suggest was “creative tension” between Blair and Brown. “I remember my first meeting with George as his PPS: he took me down to lunch at the canteen in the Treasury, with Rupert Harrison, his chief of staff, and one of the first things he said was, ‘You will learn a lot of things in this job about what we’re doing and what our plans are – obviously you’ll know to keep it discreet, but if you ever get asked by anyone that works in No 10’ – he named a couple of people like Ed Llewellyn, the chief of staff, or Kate Fall, the number two – ‘any of the key people, you always tell them everything you know; never hide anything from No 10.’ Can you imagine Gordon Brown having that kind of conversation with you, Ed?”

Balls replied: “Yeah. No.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments