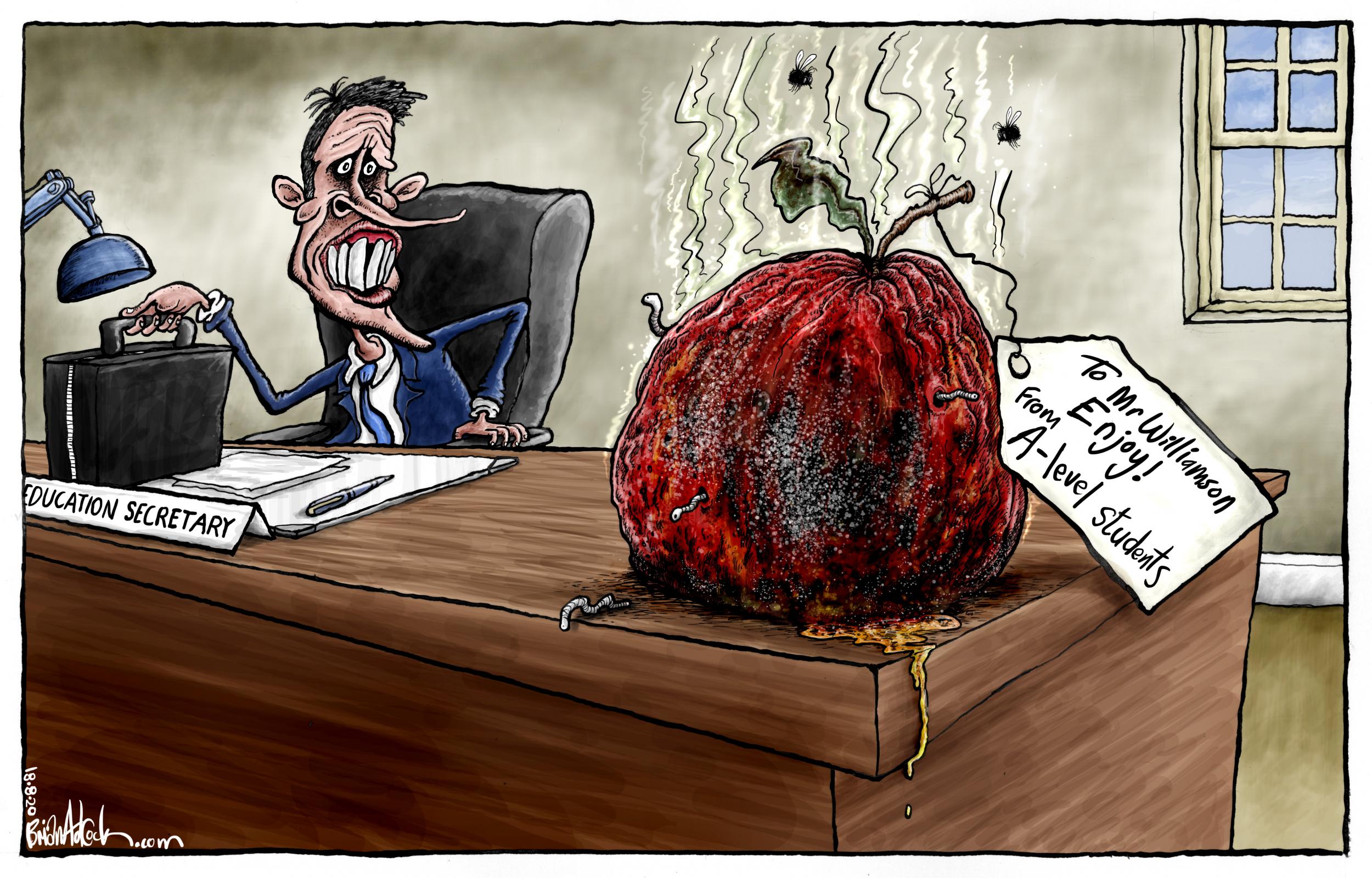

The exam grades fiasco calls into question Boris Johnson’s judgement

Editorial: The prime minister needs a clear-out of underperforming ministers like Gavin Williamson. U-turns are becoming all too common

The government has finally bowed to the inevitable and accepted that A-level grades for students in England will be based on their teachers’ assessment rather than an algorithm which downgraded almost 40 per cent of teachers’ predictions.

Gavin Williamson, the education secretary, ensured it was Ofqual, the exams regulator, which announced the belated U-turn, but this was a fiasco of his making. He drew the wrong conclusion from events in Scotland, where the SNP government performed the same volte-face to prevent discrimination against pupils from disadvantaged families.

By ruling out repeating the about-turn in England, Mr Williamson put his own prospects ahead of those school pupils who have already endured a very difficult final year. Understandably, he and his deputy Nick Gibb wanted to prevent grade inflation. They should have realised that, for one unprecedented year without exams, this is a lesser evil than unfairly blighting the futures of tens of thousands of young people.

Ofqual devised a system to avoid the inflation ministers told it to prevent, so it was acting under orders. While the buck stops with the politicians, the exams regulator is not without blame. It contributed to the chaos by withdrawing its guidance on how the new appeals system would work only hours after it was published. Its leaders were conspicuously absent from the media airwaves when students, parents, heads, teachers and university administrators urgently needed to hear from them.

The welcome climbdown will not necessarily end the anxiety and confusion for students who have accepted places at other universities after being rejected by their first choice on the basis of flawed grades. Some might now get a second chance but places on many courses have already been filled. Some students might be offered a place in a year’s time. The government should limit the damage by helping the universities to avoid further distress for students who have already suffered enough of it.

It is a political disaster for a government committed to “levelling up” to somehow manage to “level down”. Without the outcry from students (including those who took to the streets), schools, Tory MPs and even some ministers, this “one nation” government would have pressed ahead with a system that handed private school pupils an advantage and which penalised the very young people from disadvantaged backgrounds Mr Johnson purports to champion.

It apparently took a personal intervention from Mr Johnson, who interrupted his holiday in Scotland for a conference call with Mr Williamson, to bring this shameful saga to an end, and prevent another disaster when GCSE results are published on Thursday. They, too, will now be based on teacher-assessed grades.

Mr Williamson’s handling of this issue has confirmed beyond doubt that he is out of his depth. He had already presided over a U-turn on free school meals, and failed to deliver pledges for all primary school pupils to return to their classrooms before the summer break and to provide free laptops for pupils. He had five months’ notice of A-level results day, but still failed to prepare adequately, rushing into a panicky, last-minute response when he saw the problems in Scotland.

However, this affair also calls into question Mr Johnson’s judgement in appointing him to such an important post in the first place. Mr Williamson might have been an effective chief whip, but he does not have the grip on policy or communications skills needed for a front line job. His performance has reinforced the damaging impression of an incompetent government at the mercy of events.

For his own sake, and the country’s, Mr Johnson should learn his lesson; the shambles over exam grades is a direct result of his decision to appoint a cabinet on the basis of their Brexiteer credentials or personal loyalty to him. This autumn, he should clear out the under-performers and appoint a more balanced ministerial team solely on merit.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments