Weirdo, political misfit or Boris Johnson’s brain? Who is the real Dominic Cummings?

As the prime minister’s chief adviser prepares to leave his position by the end of the year, Sean O'Grady looks at the man behind the Durham lockdown furore and his controversial history

Dominic Cummings is not a Conservative. Despite being “chief adviser” to one Tory leader, Boris Johnson, and “director of strategy” for another (Iain Duncan Smith, a brief and unhappy liaison), despite delivering Brexit and the 2019 election victory, despite being married to an editor at The Spectator and politically hitched to Michael Gove for 15 years, and despite generally kicking around right-wing circles, he is not a member of any party, never has been, and, in point of fact, cordially loathes all politicians. This, by the way, does include Conservatives, many of whom he has disparaged as “public school bluffers”: which seems kind of ironic right now. Perhaps Cummings is his own one-man entryist movement, dedicated to Cummings-ism.

The dislike is mutual. David Cameron, who never had the displeasure of meeting him, famously described Cummings as a “career psychopath”. Theresa May had no time for him or Gove. Sir Roger Gale, veteran Tory backbencher, called him an “unelected, foul-mouthed oaf”, while in May, following the Barnard Castle debacle, scores of Conservative MPs campaigned to get “Dom” sacked. Nigel Farage, a rival in the Eurosceptic universe, said he was one of “the nastiest individuals I have had the misfortune to meet” (and he’s met a few), and someone “I would not put in charge of the local sweet shop”.

In the snatches of Cummings the public sees on the news, the public glimpses a loping figure unable to hold his tongue, telling the hacks to get out of London more (pre-irony) and read books. The “no regrets” rose garden press conference softened things, but not by much. The press calls Cummings Svengali, Rasputin, Machiavelli... Boris’s Brain. Still, Benedict Cumberbatch, who played Cummings in the hit TV drama Brexit: The Uncivil War, said he had “a very even keel about him... and yet he has a sense of humour and can laugh at himself and other things”, adding: “He’s not a sociopath.” Cumberbatch had prepared for the role by going round for dinner with Cummings and his wife in Islington, where they live with their four-year-old son: “I noticed the way Dom holds his hand over his head. The way he strokes his head a lot. And he rests the crook of his elbow at the top of his skull. He opined strongly, but he listens deeply too. What else? That soft R.”

The man who gave Cummings what was one of his first jobs is less charmed. The public school-educated Cummings left Oxford with a first in ancient and modern history and a passion for Russia, inspired by his tutor, Norman Stone, a brilliant if controversial scholar. At the age of 23, Cummings, ever the adventurer, went to work for a small start-up airline, running services from Vienna to Samara, a southern Russian city.

His then-boss, Adam Dixon, recalled to the Daily Mirror Cummings being drawn to the anarchy of 1990s Russia, and noted his “enthusiasm for the daring and resolve of the Bolsheviks’ ruthless seizure of power through well-applied force and extremely effective propaganda”. In such a context, packing Jacob Rees-Mogg off to Balmoral to get the Queen to prorogue parliament, although more polite than the storming of the Winter Palace, makes a kind of sense. So does “Get Brexit Done” in a “peace, land, bread” sort of way.

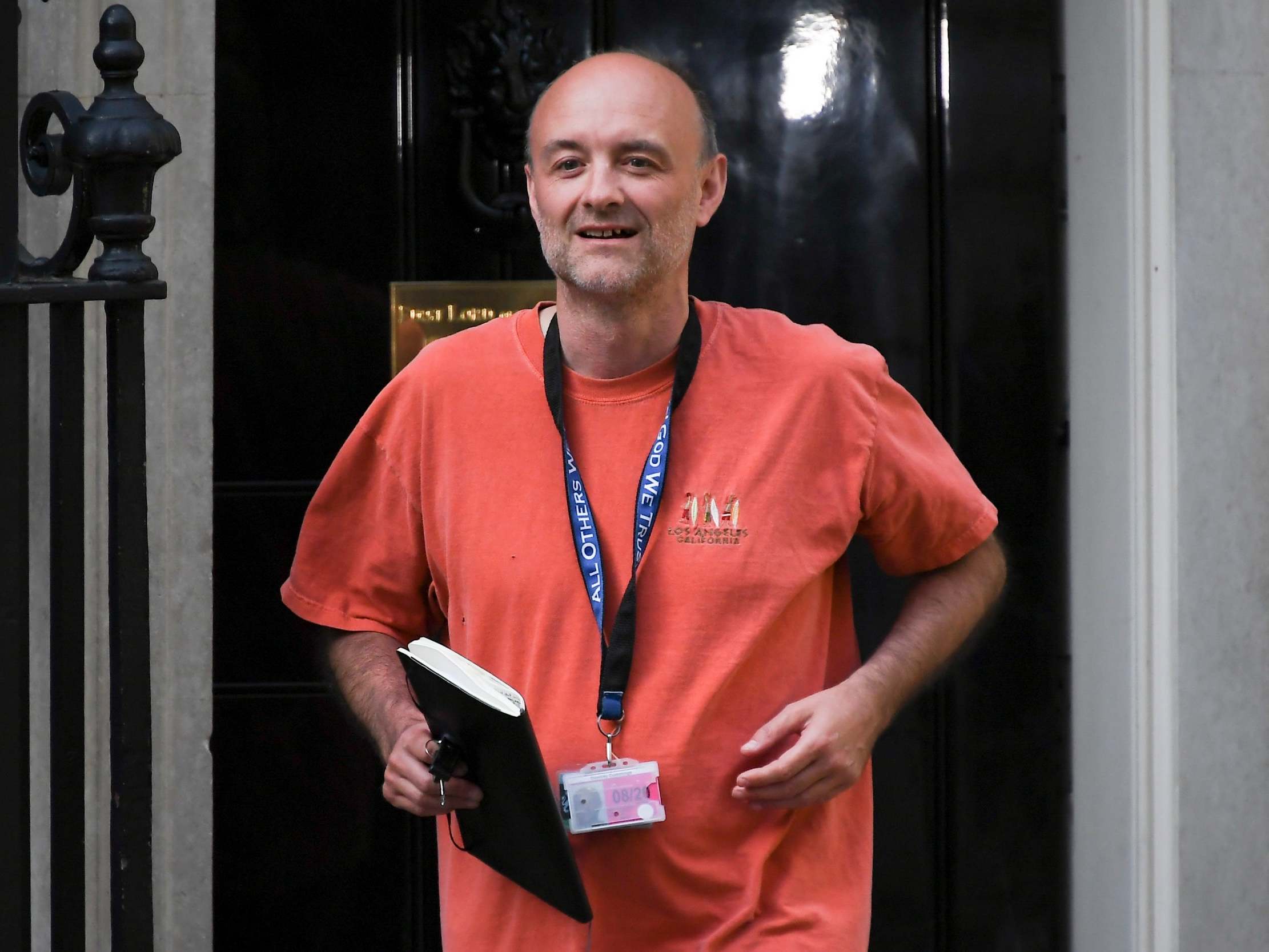

The distinctive Cummings look seems to have been set by then too. Today he wears a grey beanie, quilted navy gilet, sportswear, tote bags and sloganeered lanyards. The last one out bore the motto of US Naval Intelligence: “In God We Trust. All Others We Monitor.” Cummings has the distinction of being the first person to display “builder’s cleavage” on the steps of No 10. But then he was always a bit boho. His Oxford contemporary Lebby Eyres recalls the group of friends called “The Wastrels”, who would drink whisky into the early hours and play endless games of chess. Then as now, he enjoyed the company of “weirdos and misfits” – what he once termed “true cognitive diversity” – and an almost wilful eccentricity and individualism.

Dixon recalls: “I gave him responsibilities he quickly led me to regret. He leveraged the fact we now ‘needed him’ to sometimes behave as he liked. Left to himself, he would dress out of his laundry bag... He was usually unshaven and often looked hungover, unwashed. On the other hand he was courageous, clear-thinking and could hold his drink, which was more of an asset than it should have been.”

What Cummings is politically is more difficult to nail down. He is certainly something of a libertarian. Another one of the many short episodes that litter his CV was a spell in charge of The Spectator website back on 2006 – he was indeed himself a journalist, a breed he mostly holds in contempt. It took a remarkable amount of self-possession for Cummings to decide to publish the famous incendiary cartoon of the prophet Muhammad with a bomb fizzing on his head. It had just appeared in a Danish publication and every other organisation in Britain declined to show the pointlessly offensive image. Cummings does not seem to have asked anyone’s advice about doing it, and it was soon enough taken down, but the act was indicative, if not typical of the man. For good measure, the cartoon was accompanied by a text that said “as European populations die and Muslim populations grow, and as more and more European students are taught Foucault and ‘literary critical theory’, the balance of power shifts every day; meanwhile Britain’s comic political class cannot even control Islamic terrorists when they finally lock a few up in prison...” That may or may not have had much to do with Cummings, but it was published on his website.

Cummings is, obviously, an idiosyncratic iconoclast. Ever since he was taken on by Gove as an adviser, after his scrapes at The Speccie (he was there just after Johnson’s editorship) he made it his mission to smash Whitehall. Despite Cameron’s periodic attempts to get rid of him, Cummings spent enough time at the Department for Education with Gove during the coalition government to develop a visceral hatred of Whitehall: “It was impossible to distinguish between institutionalised incompetence and hostile action,” he later commented. He and Gove communicated via private emails as they battled for their free schools, against the education establishment “blob”. A friend summarised the pair thus: “Both Gove and Cummings had an almost Leninist belief – almost Trotskyist perhaps – that you have to permanently revolutionise. Institutions have this incredibly strong drag effect and unless you are zealously fighting to push through your reforms they will die.”

In the 250-page resignation letter he wrote in 2013, among references to genetics, philosophy, space travel, Thucydides and Dostoevsky, Cummings devoted a chapter to: “The Failures of Westminster & Whitehall: Wrong people, bad education and training, dysfunctional institutions with no architecture for fixing errors.”

The point of all this – for today – is the Cummings view that the establishment, especially the machinery of government and the EU, are or were obstacles to progress, to making Britain the “best place in the world for science and technology” and for “those who can invent the future”.

He said that after Brexit the country will be in a position to “build the kind of networks you need between science, venture capital, universities etc which are impossible to organise now with Whitehall”. He championed the idea of setting up a British DARPA (America’s Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, founded in 1958 and an IT pioneer). “Not being bound by all the ludicrous rules of the EU you can make yourself a centre where people who want to lead the technological revolutions come to work,” he said.

His enthusiasm for the future sometimes makes him sound like he’s auditioning for Doctor Who. In one interview he talked of “new institutions we need to deal with things like gene drives, lethal autonomous robotics, you name it”. A recent Cummings scheme to transform the Cabinet Office into something like mission control at Nasa was narrowly averted.

Inside that lightbulb head resides a restless intellect. Between leaving the job in education and taking on the Vote Leave organisation in late 2015, Cummings spent a couple of years sequestered on his father’s now-famous estate, off-grid, “reading science and history and trying to understand the world”. Some of the fruits of this are to be found in his blog, dominiccummings.com. He is particularly taken by the ideas of Colonel John Boyd, an American military strategist with some credit for the first Gulf War and the OODA loop – observe-orient-decide-act methodology of dealing with a flat-footed enemy (eg the Remain campaign). Also of use to the curious reader is the Nash Equilibrium, a branch of game theory that deals with the outcomes of stalemates, such as the one that prevailed on the Western Front during the Great War, or between Downing Street and the media last week. A favourite book is High Output Management by Andrew Grove, once head of Intel. Published in 1983, the book about entrepreneurship is everything Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal is not.

The fact that Cummings was able to take such time out for his autodidactic expedition also reminds us that, for all his populism, this is a man who comes from one wealthy family and has married into another. His wife Mary, who wrote her lockdown diary for The Spectator without mentioning where they were, is from the Barings banking dynasty. Not only is Cummings temperamentally inclined to walk away from uncongenial surroundings, and use the threat to get his way, but family wealth must mean he can also afford to carry out the threat.

More than anything, though, Cummings is, like Gove but unlike Johnson, a committed and longstanding Eurosceptic. He was involved in the anti-single currency group Business for Sterling 20 years ago and has lived and breathed and thought intently about the arguments for a very long time. In 2004, he also learnt about political communication when he worked on the successful referendum campaign – which had the catchy slogan “They Talk You Pay” – against devolution and an elected northeast assembly.

Cummings’s flair for devising smart, storytelling slogans – take back control, get Brexit done, levelling up – is well appreciated, even though it’s not that novel; the Tories and New Labour had been reflecting what focus groups said back to the voters for decades. What was more innovative in the Leave campaign was the use of data – electoral, polling, datasets “scraped” off the internet to target political adverts at individual voters. Cummings worked out that linking the EU to the NHS was a vote winner; and he pushed the line about Turkey joining the EU. Cummings and Gove also had the crucial insight that any Leave campaign was bound to lose if it was headed up or associated with loons such as Farage or bores such as Tory backbencher Bill Cash.

Another of Cummings’s heroes is said to be Otto von Bismarck, architect of the German nation state and titan of diplomacy. Eventually a new kaiser came along and fired Bismarck, and there was a famous cartoon by John Tenniel of the sad but dignified ex-chancellor departing the ship of state, with the caption “Dropping the Pilot”. One dayin the not too distant future, Cummings will drop himself, but he can content himself today with the thought that, not quite 50 years of age, in terms of his continental impact he is something of a Bismarck of his own time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments