‘I can live freely’: Life in Britain after fleeing Hong Kong

Rory Sullivan speaks to Hongkongers about their experiences of moving to the UK to escape China’s crackdown

Many countries have denounced Beijing’s muzzling of freedoms in Hong Kong, but the UK stands alone in offering sanctuary to millions of people from the territory.

The human rights situation in Hong Kong, febrile for a long time, worsened dramatically last June when China imposed its harshest crackdown yet on civil liberties in the former British colony through the introduction of a new national security law.

Since then, hundreds of people have been detained on spurious grounds under the legislation, which criminalises catch-all terms such as subversion and collusion with foreign powers. As a result, thousands have decided to leave their home town and head overseas, not knowing when - or if - they will return.

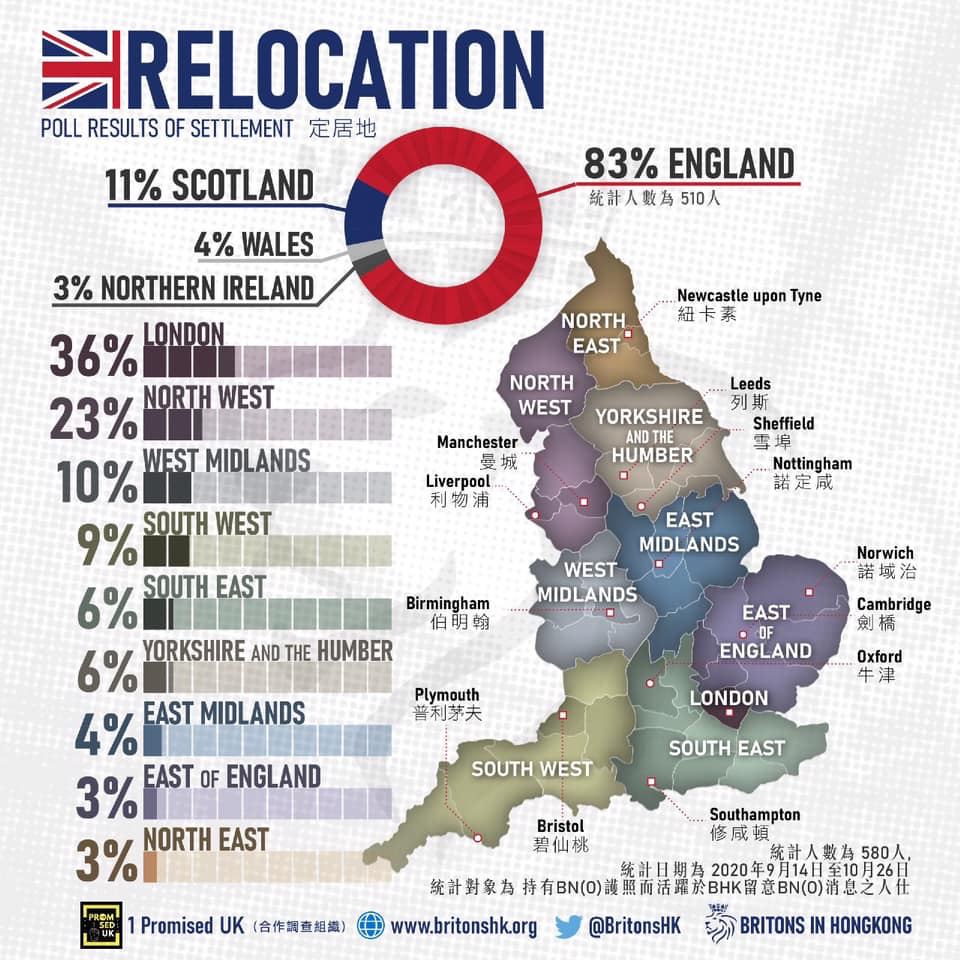

In response to the Chinese Communist Party’s strong-armed tactics against the pro-democracy movement, the British government announced last summer that it would grant visas to Hongkongers with British National (Overseas) status (BNO), a class of citizenship granted by London before it gave sovereignty over Hong Kong to China in July 1997.

In total, 2.9 million BNO status holders are eligible to move to the UK, as are 2.3 million of their dependants, according to government estimates. Under the scheme, those who come to the UK can apply for British citizenship after five years living in the country.

The BNO visa scheme officially launched at the end of January, with more than 35,000 Hongkongers applying within the first 10 weeks. As such, experts believe that the Home Office has underestimated the potential number of arrivals over the next five years, which the department predicted would be between 258,000 and 322,400.

Simon Cheng, a 30-year-old from Hong Kong, is familiar both with China’s violent suppression of democracy and with the challenge of making a new life in the UK.

While working for the British consulate in Hong Kong, Mr Cheng made global headlines in 2019 when he disappeared during a business trip to mainland China. It later emerged that he had been arrested by the Chinese authorities, held for 15 days and allegedly abused. “I’ve been tortured, I’ve been blindfolded, handcuffed, hooded, shackled. Like a very serious criminal,” he tells The Independent over Zoom from London.

His detention came after he had collected information on the protests for the UK consulate.

Following his release from custody, he managed to flee to Taiwan and after a months-long wait was able to travel to the UK, where he was offered refugee status on 26 June, 2020.

In addition to his day job working for the census, Mr Cheng spends his time volunteering for Hongkongers in Britain (HKB), an expat organisation he co-founded to help new arrivals from the territory.

HKB offers guidance to newcomers and also wants to help them integrate into UK society. “We set up an expat organisation because we wanted to at least mitigate the risks of anti-immigration sentiment, which have been very prevalent in the last few years,” Mr Cheng explains.

“It is not enough to just open doors for people to come here. Without equal or fair opportunity as a launchpad, it potentially causes social issues in the future.”

Like other similar initiatives, HKB has been inundated by requests from Hongkongers since it was set up last year. As well as asking about the BNO visa scheme itself, people seek advice on issues including how to find accommodation, set up bank accounts, register for a National Insurance (NI) number and apply for schooling.

Mr Cheng spells out the difficulty of these people’s predicament: “About the future, they still have a deep sense of insecurity. Even after making the choice to come to the UK.”

Jabez Lam, project leader at Hackney Chinese Community Services (HCCS), a local organisation helping Hongkongers, has also been receiving a high volume of requests. The pandemic has obviously made things harder, he tells The Independent.

“We’re especially stretched - it’s all happened during Covid. But it’s just something we have to respond to,” he says.

“These are very resourceful people. Many of them are skilled and they can make a great contribution to British society. But the main issue is that they need the proper support when they arrive to enable them to integrate properly.”

Given the evolving government guidance, Mr Lam says HCCS is learning all the time. “This is still an early stage. We’re better informed than at the start but we by no means know everything,” he explains.

Although he credits the government with listening and acting on HCCS and other groups’ feedback, Mr Lam believes certain areas could be improved, such as speeding up the NI number process. As an example, he cites a single parent who, months after her arrival, is still struggling to find a job because she lacks a NI number.

Housing, however, is the “top area of concern”, according to a government-commissioned consultation by HKB, HCCS and the Hong Kong Assistance & Resettlement Community (HKARC). One prominent issue is landlords who refuse prospective BNO tenants’ applications over mistaken fears that they do not have the right to rent.

Hongkongers who do not have BNO status - and are therefore not eligible for the government’s scheme - face even more uncertainty, as they normally have to seek asylum. This usually affects people born after 1997 as well as those who did not register before the UK ceded power in Hong Kong.

Moving to the UK was a difficult decision. But now that I’ve come here, I don’t have to worry about my personal safety. I can live freely

H, who wished to remain anonymous, is one of those who has fallen through the cracks. Arrested in Hong Kong at the start of July for his involvement in the protest movement, he reached the UK in January, soon after his parents were detained by police in the territory.

Since he does not have BNO status, H, who is in his 20s, claimed asylum after reaching the UK and awaits his second immigration interview. He has bad memories of the first one, which took place at the airport. “One of the immigration staff told me that I was a liar,” he alleges, saying they refused to believe that he was a protester and was in danger in Hong Kong. “It was really hurtful to me.”

A Home Office spokesperson says they are unable to comment on the incident without more information and mentions its “proud record of providing asylum for those who need it, where there is a well-founded fear of persecution”. They also point to the BNO visa scheme as “an unprecedented and generous immigration offer reflecting our deep connection with Hong Kong”.

H says he was treated far better by his neighbours in the Midlands, who went out of their way to help him. Nevertheless, he is short on money and cannot claim government support. “I just try to spend the minimum. For example, I go to the food bank or wait for supermarket promotions.”

Being so far from home and in such a precarious situation, he is mulling a move to Taiwan if he is granted a visa. “My experience has been just like the UK’s weather: sometimes sunny, sometimes cloudy, sometimes rainy and sometimes snowy.”

Others have had it slightly easier. Reese, whose BNO visa was confirmed recently, moved to London last autumn and now works as an administrator in the NHS.

Reese says he is grateful to the UK government for the visa initiative, which gave him the chance to live without fear. “I wanted to come here to have a fresh start and to see how I can help build the identity of Hongkongers here.

“Moving to the UK was a difficult decision. But now that I’ve come here, I don’t have to worry about my personal safety. I can live freely.”

Like H, he notes how “helpful and friendly” people in the UK have been. “They really want to see how they can help us, how they can treat us as one of them,” he says.

Despite knowing that he is unlikely to see his family “any time soon”, Reese is cautiously optimistic for his future in the UK, a contrast to his pessimism about events in Hong Kong. This chimes with Mr Cheng’s sentiments. “I’ve sacrificed a lot: I can’t contact my family and I can’t return to my home town. And perhaps that’s strengthened me - it’s momentum to keep pushing the pro-democracy campaign,” the HKB founder says.

Once lockdown restrictions ease, Reese is keen to make new friends and explore the UK, having never been outside of London before. “I’ve been told about so many places I need to see,” he says, adding that Bath and Edinburgh are currently top of his list.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments