Not one woman's name included in GCSE science national curriculum, study finds

Only half of adults can name a female scientist, writes Maya Oppenheim

The national curriculum for GCSE science does not include the names of any women, and only half of adults are able to name a female scientist either dead or living, a new study has found.

Teach First, which carried out the report, found that men dominated the GCSE science national curriculum, which includes over 40 male scientists or ideas or materials named after them.

The social enterprise, which strives to tackle disadvantage in the education system, warned that groundbreaking scientists such as Marie Curie are at risk of being wiped from the public consciousness.

Researchers discovered that only Rosalind Franklin and Mary Leakey are referred to when looking at three double science GCSE specifications from leading exam boards.

Leakey, a British archaeologist and anthropologist, discovered the first fossilised Proconsul skull, which belonged to an extinct ape now deemed to be an ancestor of humans. The research of Franklin, a British biophysicist and x-ray crystallographer, sparked the unearthing of the structure of DNA.

Franklin has been described as “the woman who was not awarded the Nobel Prize for the co-discovery of the structure of DNA”.

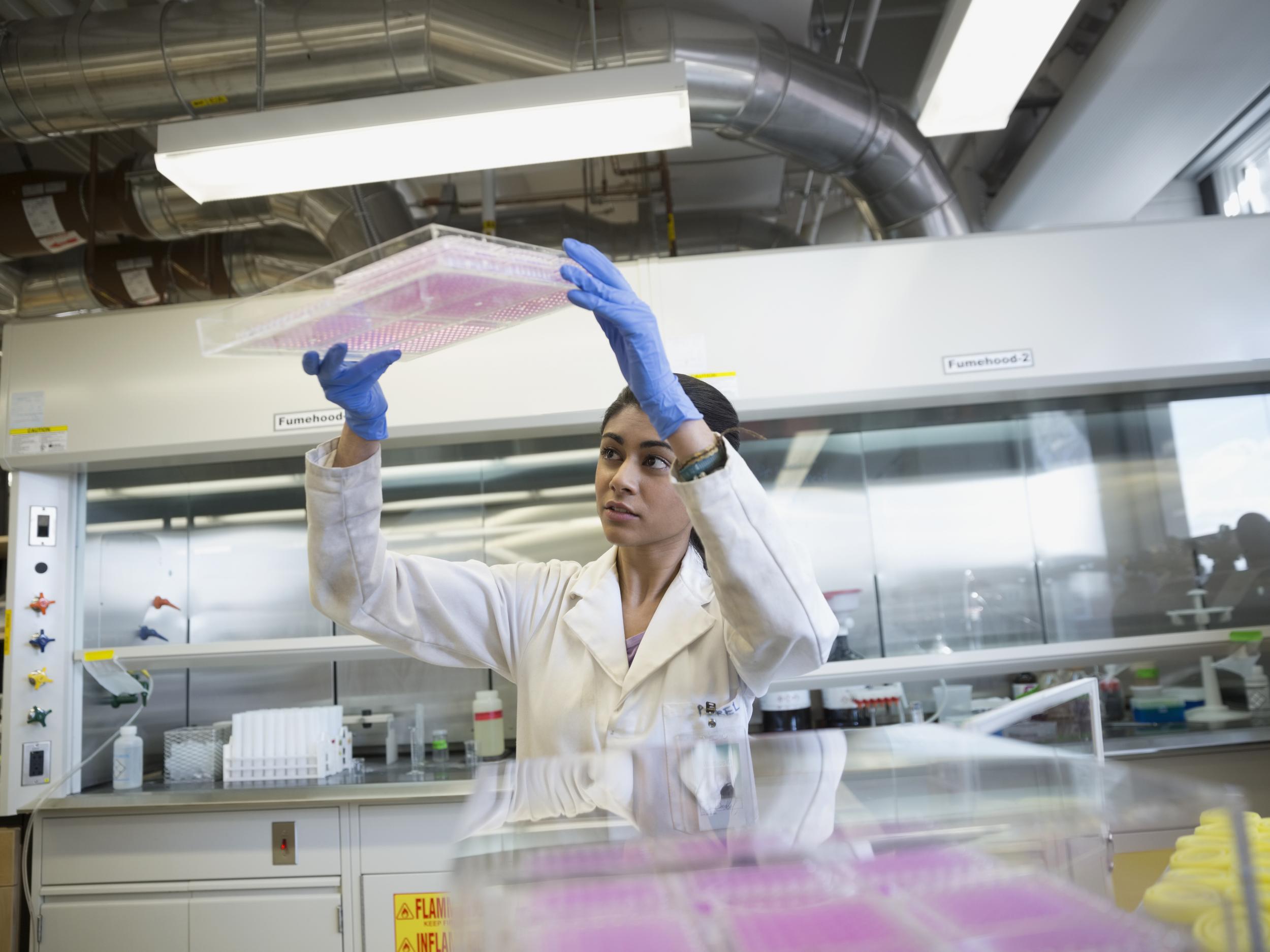

A dearth of role models for young girls is exacerbating already entrenched gender prejudices and stereotypes, prompting fewer girls to opt to study science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) subjects after GCSE, Teach First warned.

The charity found that girls from disadvantaged backgrounds are most likely not to choose such subject areas and are seven times less likely to pick A-level physics than a boy from a more advantaged background.

Konnie Huq, the TV presenter who was the longest-serving female member of Blue Peter, said: “It’s really disappointing to see trailblazing female scientists, who have changed the world with their pioneering discoveries, being overlooked in schools and in the public eye.

“By not celebrating these incredible individuals, we’re unconsciously showing girls that STEM isn’t for them. This simply isn’t good enough.”

Ms Huq, the ambassador of Teach First’s new STEMinism campaign, added: “It’s time to get more inspirational female role models into classrooms and celebrate schools who support girls to continue their interests in STEM subjects. Let’s break down those archaic gender barriers and create a country where every girl can achieve anything she puts her mind to.”

Teach First’s campaign argues that the underrepresentation of women in STEM careers needs to be overhauled and is looking at ways to get more girls to pursue further study or a career in these industries after their GSCEs.

The charity’s report found that just 12 per cent of engineers are women and 13 per cent of STEM workers in senior positions are female, but a lack of STEM expertise costs businesses £1.5bn a year.

Shelley Gonsalves, the organisation’s executive director, said: “While being stuck on the question of how to get more girls to pursue science technology, engineering and maths, we’ve overlooked that there are too few women celebrated in these subjects at school for girls to see.

“This matters, because if girls don’t see identifiable role models it’s hard to spark their imaginations to pursue STEM careers in future. This leaves talent unlocked, which exacerbates our country’s STEM skills shortage.

“Great teachers have an incredible role to play here, especially when given the right support and tools to make sure there is greater representation of girls and women. We especially need to overcome the double disadvantage faced by poorer girls by incentivising more talented people to become teachers and help their pupils thrive where the need is greatest.”

Only men were bestowed with Nobel Prizes in science last year, and critics have often hit out at the lack of women winning such accolades. While Donna Strickland won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics, she was only the third female physicist to be given a Nobel in the history of the prize.

Research has repeatedly demonstrated that women in STEM areas come up against implicit bias and concrete obstacles to career progression.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments