The Indy Film Club: How Blow Out proves that film can’t show us the truth

Jean-Luc Godard may have labelled cinema as ‘truth at 24 frames per second’, but Brian De Palma used his 1981 psychological thriller as the perfect counterargument, writes Clarisse Loughrey

A good scream is hard to find. Tears can be switched on like a tap. A smile is just a twitch of the muscles. But a scream isn’t produced. It erupts, deep from within the fleshy caverns of someone’s lungs. Blow Out’s notorious shriek, let out by Nancy Allen’s Sally in the film’s final reel, is no ordinary sound. It’s a death cry – a final expression of utter hopelessness, which her lover Jack (John Travolta), a sound designer, then adds to the tacky slasher film he’s working on. “Now that’s a scream!” his producer exclaims. But the result feels uncanny. A slasher film isn’t reality. It’s an illusion, a ritual. We never connect it to the idea of real human loss.

Blow Out from 1981 – a terrific psychological thriller mixing the paranoia of The Conversation with Hitchcockian suspense – questions film’s ability to show us the truth. It’s a surprising stance for its director, Brian De Palma, to take, considering he otherwise treats the medium with such divine reverence. He’ll absorb the wisdom of his predecessors, then carefully replicate it on screen. He has a particular affection for Hitchcock and his preoccupation with sexual obsession, voyeurism, and violence – explored with a sense of absolute precision and control. Those themes crop up in Blow Out, though it also riffs heavily off Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966) and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974). In Blowup, a fashion photographer becomes convinced he’s captured a murder on film. In The Conversation, it’s a wiretapper who’s recorded two people seemingly planning a homicide.

Here, it’s a political assassination that our protagonist, Jake, believes he’s caught on tape. One night, he ventures out to record a few ambient sounds – an owl, a couple’s whispered conversation, the wind rustling through leaves. Suddenly, a car swerves into view. There’s a bang. It plummets into the river. Jake dives in to rescue the woman in the passenger seat, Sally, but later discovers that the driver was a presidential hopeful. When he listens back to the tape, he realises there were in fact two bangs. One was the blowout. But before? He’s sure he can hear a gunshot.

Jack rewinds and replays the tape, trapped in an endless loop. When he gets his hands on a set of photographs of the incident, he attempts to fuse sight and sound together in perfect harmony. But De Palma repeatedly uses his own camera to remind us that Jack will never find the objective truth. He’ll manipulate our view by shooting overhead or using a split-diopter lens – where both the foreground and background are given equal focus. These techniques direct us where to look. They instruct us on how to think and feel. A dizzying 360 shot of Jack’s studio, filled with whirring mechanics, injects a sudden sense of dread. No one has to speak a word for us to sense that something’s gone terribly wrong – his tapes have been erased by an unseen hand.

Blow Out was a surprisingly sober, reflective film for De Palma at this juncture in his career. His early films were often politically flavoured – Greetings (1968) features a JFK conspiracy theorist – but he’d grown more provocative over the years. Blow Out’s opening sequence, which jumps into the film Jack’s working on, is a Steadicam shot from the point-of-view of a stereotypical slasher killer. It’s wall-to-wall tits. While it’s primarily a parody of John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), there’s a nod, also, to De Palma’s own history of lurid eroticism, in the likes of Dressed to Kill (1980) or Sisters (1972).

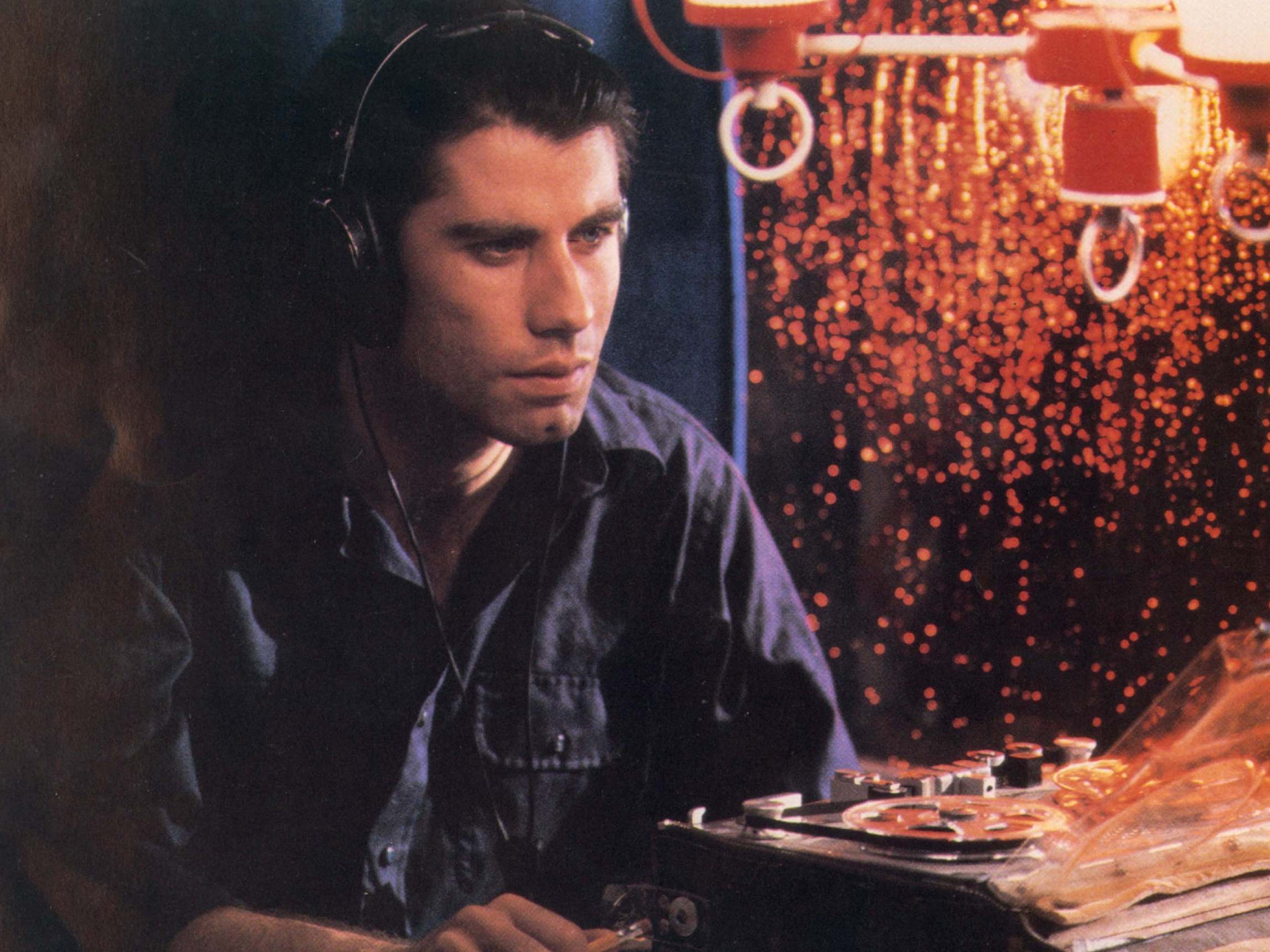

Despite an estimated budget of $18m, the same as Raiders of the Lost Ark, released that same year, Blow Out flopped at the box office. Quentin Tarantino had a big hand in salvaging the film’s reputation – he listed it as one of his all-time favourites and the reason he cast John Travolta in Pulp Fiction. That’s despite the fact that Vincent Vega is nothing like Jack. Travolta is at his sweetest and most vulnerable here. His baby blue eyes are always clear and attentive.

Audiences had expected more lurid eroticism, what they got was a thriller moored in the paranoia of post-Nixon America, packed with references to the Watergate scandal, the JFK assassination, and Ted Kennedy’s Chappaquiddick incident. Add to that, a drop of (not-so-subtle) irony: the film takes place in Philadelphia during the run-up to the fictional Liberty Day. There are brass bands, fireworks, and American flags several stories tall. It creates a cacophony of sound that nearly drowns out Sally’s piercing, haunting scream – she’s killed to cover up her involvement in the crash. One image of America, a patriotic burlesque, obscures a more truthful one. Jean-Luc Godard may have labelled cinema as “truth at 24 frames per second”, but De Palma himself used Blow Out as the perfect counterargument. As he put it: “The camera lies all the time; lies 24-times-per-second.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments