Stargazing in April: A planetary hit-and-run

There are a number of space oddities in our solar system, writes Nigel Henbest. And they may all be related

This month, we have not just one “evening star”, but two. Both the planets that lie closer to the sun are on view after sunset. Venus is so brilliant that it outshines everything in the sky, bar the sun and the moon. Down in the dusk twilight you’ll find fainter Mercury, which never strays far from the sun.

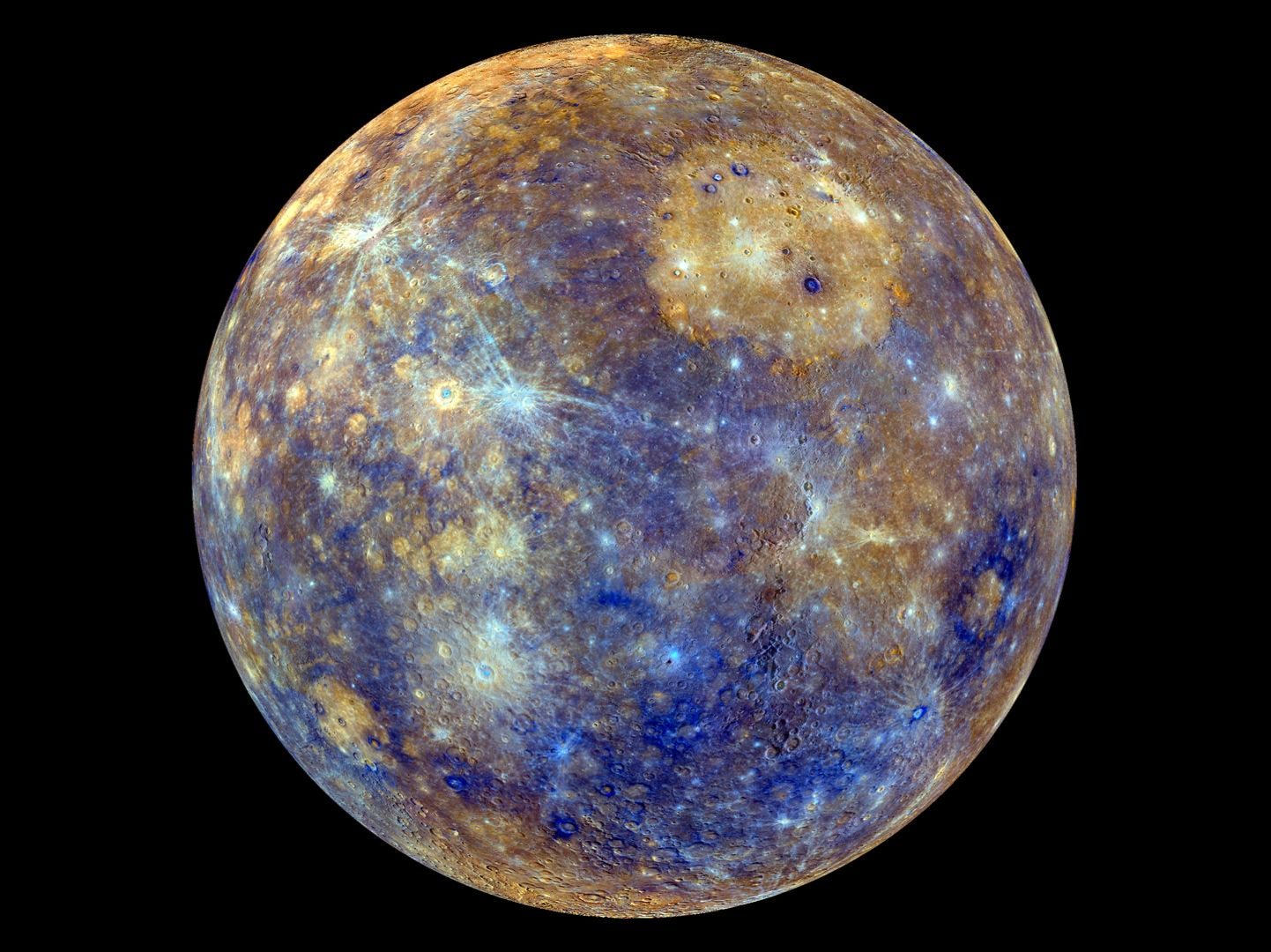

Space probe missions to these worlds have shown them both to be space oddities. Mercury is made almost entirely of iron, like a planet-sized cannonball with only a thin veneer of overlying rock. Venus rotates very slowly, and the opposite way to the other planets. While we’re on the subject, our own planet is pretty unusual too: it has a companion so large that astronomers view the Earth-moon system as a double-planet.

Now researchers are beginning to think that all these odd characteristics could be related. It involves several cosmic hit-and-run incidents when the planets were young and reckless, with Mercury as one of the prime culprits.

The investigation started with our moon. When scientists examined the moonrocks brought back by the Apollo astronauts, they found that its crust is strangely depleted in elements that boil away at moderate temperatures, such as potassium, zinc and silver. The moon’s surface must once been incandescent enough to evaporate away these metals. Add to that the fact the moon doesn’t have an iron core – like the Earth and our neighbour planets – along with its size, and our companion world was an enigma.

In 1969, American astronomers Bill Hartmann and Don Davis proposed a radical explanation. When the Earth was young and single, they surmised, a planet the size of Mars crashed into it. The impactor has been named Theia – but don’t go looking for it, because it no longer exists. The cosmic collision almost split the Earth in two, but gravity pulled our world back together as a fiery molten ball with – at its centre – the metal core of Theia amalgamated with the Earth’s original core.

The impact also splashed fragments of molten rock into orbit around the Earth. Briefly forming a fiery ring – like a superheated version of Saturn’s rings – this material coalesced in orbit to form the moon.

This “big splash theory” explains all the moon’s oddities. It threw up a huge amount of the Earth’s mantle rocks – along with now-deceased Theia’s – baked to tremendously high temperatures, and without any metallic material that could have formed a core for the moon.

Once scientists had accepted the apparently outrageous idea that planets in the early Solar System were bent on mutual destruction, the oddities of Venus and Mercury fell into place. Something struck the young Venus obliquely, reversing the direction it was spinning. And an impactor hit Mercury, stripping away its rocky mantle and leaving only the core.

But that left serious loose ends: where did these impactors end up, as we don’t see them today? And the problems got worse when NASA sent an orbiter to Mercury – the Messenger spacecraft – which discovered Mercury’s surface contains many of the volatile elements that are missing on the moon, suggesting the mantle was never seriously hot.

Norwegian-American astronomer Erik Asphaug and his Swiss colleague Andreas Reufer then put forward revised theory that fits these facts. Mercury, instead of being the victim, is actually the perpetrator of interplanetary hit-and-run accidents. What’s now the innermost planet started life beyond the orbit of the Earth, about the size of Mars. Swinging wildly inwards towards the sun, Mercury hit Venus obliquely, sending this planet into a backwards spin.

Unlike Theia, proto-Mercury didn’t get absorbed into the larger planet. Most of its mantle rocks were knocked off in the grazing impact, but its massive iron core carried on, and eventually settled into the close orbit around the sun where we find Mercury today. If we want to look for the missing rocky mantle from Mercury, we’ll find it absorbed into Venus.

In fact, Asphaug and Reufer’s calculations show that – before it hit Venus – proto-Mercury may have had an oblique hit-and-run incident with the Earth as well. In that case, when you look at Mercury in the sky this month, bear in mind that some of that planet’s material may be in the rocks under your feet.

What’s Up

The Evening Star – aka the planet Venus – is brilliant in the western sky after sunset. On 11 April, it passes right next to the Pleiades, the glorious little star cluster better known as the Seven Sisters – a beautiful sight in binoculars. The thin crescent moon lies near Venus on 22 and 23 April.

Mercury is well to the lower right of Venus, skulking low in the twilight glow. The innermost planet is putting on its best evening appearance of the year, but even so it’s a challenge to spot Mercury before it sets around 9.30 pm.

Surrounding Venus are the bright stars of winter, now gradually sinking from view as the year progresses. Among them you’ll find Mars. Only a couple of months ago, the Red Planet was the shining beacon amongst them; but as the Earth pulls away from the slower-moving planet, it’s rapidly fading. Towards the end of the month, Mars approaches the twin stars of Gemini, Castor and Pollux, with the moon joining them on 25 and 26 April.

In the southern sky, the crouching feline form of Leo (the Lion) rides high, with the Y-shape of Virgo (the Virgin) to its lower left. The bright star to the upper left is Arcturus, the leading light in Boötes (the Herdsman).

Look out for shooting stars on the night of 22/23 April, as it’s the maximum of the Lyrid meteor shower. These incandescent fragments shed by Comet Thatcher seem to stream outwards from Lyra (the Lyre). Though it’s not one of the year’s most prolific meteor displays, the Lyrids should put on a good show this year as it’s unspoilt by moonlight. And keep a watch out for glowing trails left behind by the shooting stars themselves.

And if you have a chance to travel most of the way around the world, there’s an unusual eclipse of the sun on 20 April. This hybrid eclipse starts in the eastern Indian Ocean as an annular eclipse, with a narrow ring of the sun’s surface visible around the moon’s silhouette. By the time the shadow of the moon has raced to Indonesia, the moon’s outline in the sky has grown slightly larger, to block the sun’s face completely in a total eclipse of the sun. Then, when the eclipse track heads out into the Pacific Ocean, we are back to an annular eclipse.

Diary

11 April: Mercury at greatest elongation east; Venus near the Pleiades

13 April, 10.11 am: Last Quarter Moon

20 April, 5.12 am: New Moon; hybrid solar eclipse

22 April: Moon between Venus and Pleiades; Maximum of Lyrid meteor shower

23 April: Moon near Venus

25 April: Moon near Mars

26 April: Moon near Castor and Pollux

27 April, 10.20 pm: First Quarter Moon

29 April: Moon near Regulus

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, Stargazing 2023 (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments