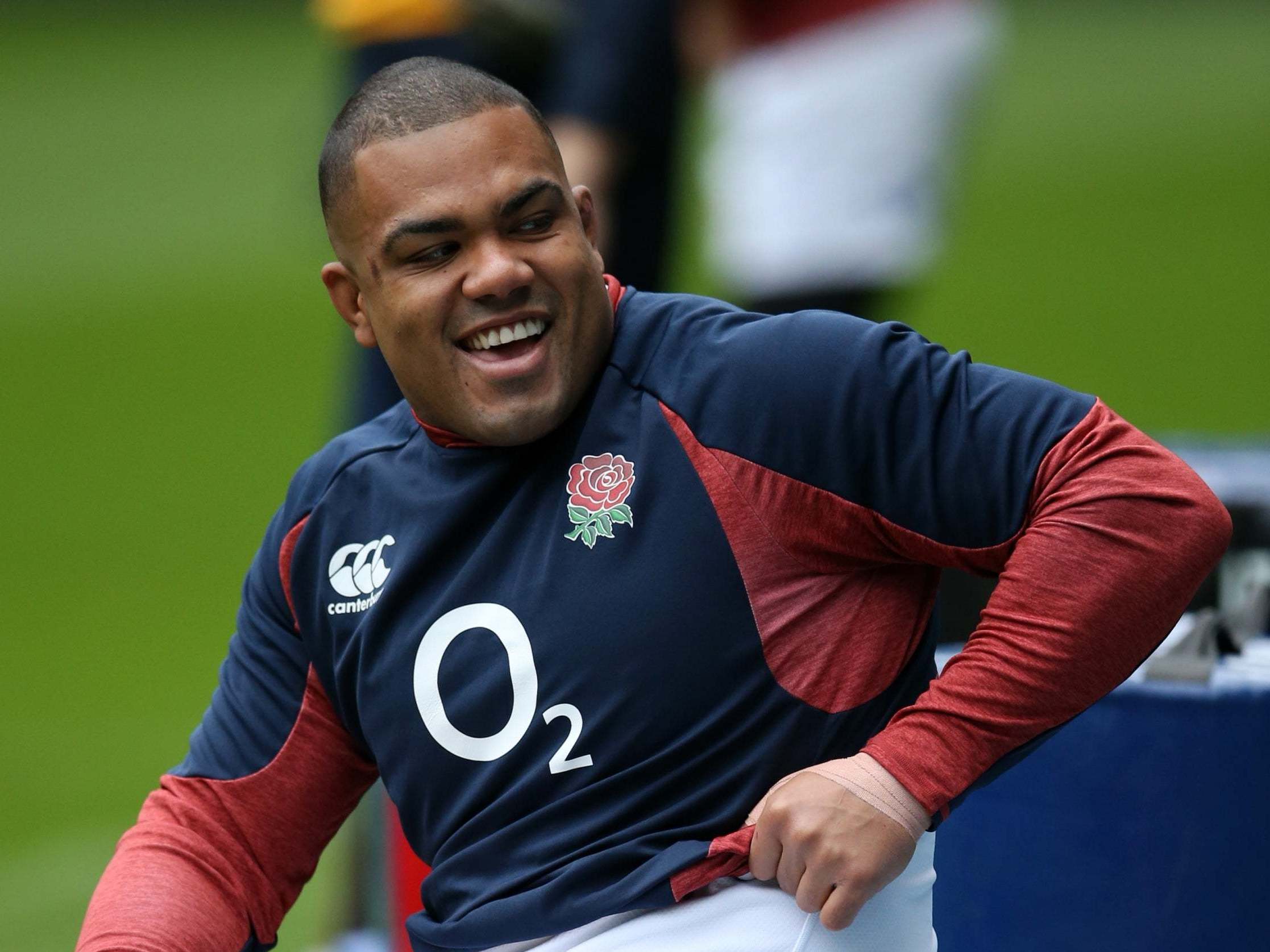

The moment that turned Kyle Sinckler’s England career around

The Londoner has proven one of English rugby’s great discoveries but, as Jack de Menezes details, it could have been very different

England prop Kyle Sinckler has set himself the task of making a difference off the field to help others like him receive the rugby opportunities they deserve, but it was the big change he made for himself that helped to turn his international career around.

The Londoner has proven one of English rugby’s great modern-day discoveries, having ousted veteran Dan Cole to become Eddie Jones’s first-choice tighthead prop and win 35 England caps and three appearances before his 27th birthday at the end of the month.

He played a pivotal role in Saturday’s 33-30 victory over Wales as England gave themselves a strong chance of Six Nations championship glory, though they will need a favour from France in their match with Ireland whenever the unscheduled final fixtures take place this year.

The win meant that England extended their five-year unbeaten home streak against the Welsh, but it meant a lot more on a personal level to Sinckler because of what happened in Cardiff this time last year.

A relatively novice Sinckler found himself targeted by Wales’s old guard, with captain Alun Wyn Jones getting under the skin of the prop and triggering something of a response to help draw penalties out of him, helping to turn the result in the favour of the Welsh and causing coach Warren Gatland to label him an “emotional time-bomb” after the match. That was Sinckler’s 23rd Test appearance of his career, but the lesson he learned that day helped him to accept that there was something in his way of making the most of his enormous potential: his ego.

“I’m very, very thankful for what happened in Cardiff because without that I’d probably have kept costing the team,” said Sinckler. “At that time my ego was bigger than this room. If I’m looking back on it, I really enjoyed being that villain – the bad boy of English rugby. I was just very angry. Very, very angry.

“It was perfect. It was exactly what I needed,” Sinckler added. “It was sink or swim because if I didn’t change then I wouldn’t have played for England any more. I cost the team a Grand Slam and at the time I was so in denial.

“I never took responsibility for what happened. I was saying life is hard, it wasn’t my fault, the referee doesn’t like me, in Cardiff you’re never going to get the rub of the green. But when you strip it back and look at it, it was just ego.

“It was ego trying to get in with Alun Wyn Jones, trying to be that bad boy, which cost the team. Now, hopefully, everyone can see, and I know myself, I am a different person. I thank Gats (Gatland), I thank Alun Wyn Jones because I feel I have grown from it and I am only going to get better.”

Sinckler has spoken previously of his background and the difficulties that pose others like him in making it in a sport like rugby union, where the dominance of white middle-class families remains a trend among English players. Having worked with Saviour World, a well-being organisation that looks the help young men discover the best versions of themselves, Sinckler was inspired to start something himself that offers help to others, which is why on the same day as his Six Nations retribution, he launched the R3cusants foundation.

“I had to harness that and do something positive and understand why I was angry and kept making the same mistake,” he said. “I needed to become a better person. My issues were never anything to do with rugby, rugby was always my canvas. It was always stuff outside of rugby and the aim of my foundation is to help kids in inner city London and give them the opportunity.

“My biggest gripe is that there are guys who I went to school with who didn’t have the means, transport or parents pushing them, or the kit or the facilities. If they get given that opportunity but don’t take it, then that’s on them.

“What gets me is when someone doesn’t get the opportunity. I want the foundation to be self-sufficient and we’ll start small. If we help one kid this year, that’s a job well done. I don’t want to do it to be seen doing good, I want to use this platform to actually make a difference.

“There aren’t many people from inner city London who are playing rugby. There are more than there were 10-15 years ago, but if you look at the talent that’s actually there, it’s an untapped reservoir. I want to give those kids an opportunity in sport, steer them in the right direction and try to use that as a positive influence. It’s then down to them if they want to take that opportunity and change their lives. We’ve got the means to help them.”

The Wandsworth-born Sinckler learned the sport at Battersea Ironsides while living with his mother in Tooting, having switched from football to rugby in an effort to control his temper as he kept getting himself sent off. Perhaps the making of him came in those days in amateur club rugby, when he had the right figures around him to ensure he did not stray from the straight and narrow.

“The one that stands out to me was Glen Petit,” recalled Sinckler. “He was a good guy. To this day, he would do anything for me and it was probably the worst and the best thing for me at the time. I could never do anything wrong. I might get sent off at 10 years old after punching someone, but it was not my fault – you know – and he would always protect me.

“I remember one tournament we had when I was 12 years old. My mum got really badly racially abused, which was an anomaly because you don’t associate rugby with that. I think the kid was trying to get under my skin. They took me off the pitch – he (Petit) and another guy, Graham Beech – and he said “cancel the game, he’s my player and he should never be experiencing that sort of stuff”, because I was fuming.

“I’ll never forget Glen and Graham and what they did for me – and Bob (Ockenden) – because without them I wouldn’t be here now.

“And obviously my mum because she would have to work night shifts. She’d be working 7pm on a Saturday until 7am the next morning and then take me to rugby. Then she’d go back to work at 7pm. We were living in Tooting and she’d have to drive me to somewhere like Dorking for a festival all day, so she wasn’t getting much sleep.

“She deserves a lot. She will be working for my foundation – she wants to help out. A few of my friends from back home will be helping out with it and I think that’s how you have to do it. If it’s always give, give, give, they maybe don’t feel that appreciation whereas if they feel like part of something, everyone buys into it more.”

There is a very clear target for Sinckler: to give back to the game he loves, and the area that made him who he is today. “The aim for me is in 10 years’ time, if I am not playing, I will be sitting on the sofa and I can say, ‘That kid came from my foundation and he is doing really well now’”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments