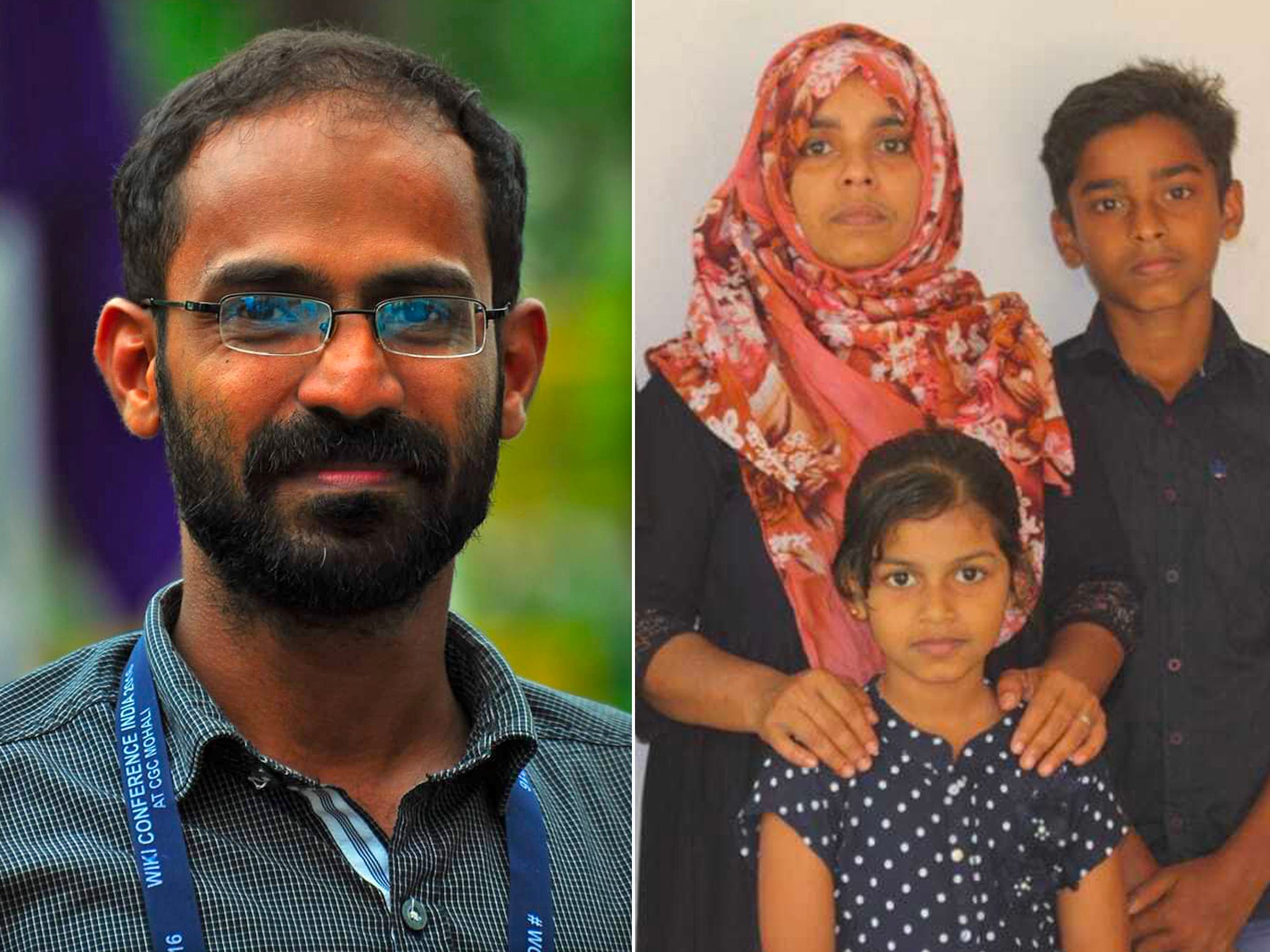

Wife of jailed Indian journalist speaks out one year after his arrest: ‘My husband has committed no crime’

Siddique Kappan’s arrest sparked outrage from journalist unions. One year on, his legal team still haven’t been given a full charge sheet. Sravasti Dasgupta reports

For over 19 years, Raihanath Kappan’s life revolved around her family and household; bringing up her three children, taking care of her ageing mother-in-law and supporting her husband.

Now at the age of 38, she has taken up the daunting task of fighting the might of the Indian legal system, as she struggles to secure the release of her husband Siddique Kappan.

Kappan, 42, is a journalist from the southern Indian state of Kerala, who was arrested along with three others on 5 October last year while on their way to report on the alleged gang-rape and death of a Dalit (formerly Untouchable) girl in Hathras, located in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh.

One year on from his arrest, Kappan and his lawyers still haven’t seen the full charge sheet against him, but it is understood he is facing allegations including sedition, inciting violence, outraging religious feelings and terror activities under the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA).

The charge sheet against Kappan claims that he and the others – identified as Atiq-ur-Rahman, Masood Ahmed and Alam – were members of the Popular Front of India (PFI), a radical Islamist organisation, and that they were travelling to Hathras in order to stir up unrest.

Police have built their case in part using news articles written by Kappan about issues relating to the alleged persecution of Muslims in India, seeking to build a case that he was not a responsible journalist.

News articles referred to in the charge sheet, according to the Indian Express, include Kappan’s writings on the religious riots in Delhi in early 2020 and protests against the government’s Citizenship Amendment Act, articles which police said were “writ[ten] to incite Muslims”.

My husband has not committed any crime, I am sure about that. They are using UAPA so that no journalist writes against the government again.

Speaking to The Independent, Kappan’s lawyer Wills Mathews said that: “It is an established fact that my client is a journalist. He has not done anything that violates the Press Council of India Act. His stories have been fair and impartial.

“Moreover, he is not a member of the PFI. Even if he was, PFI is not a banned organisation,” added Mathews.

PFI also issued a statement earlier this year, stating it believes the case to be politically motivated and that none of the men are its members.

Nonetheless, the police charge sheet, parts of which have been seen by The Independent, accuses Kappan of being a member of a terrorist organisation, intending to hurt India’s integrity on the orders of the PFI and inciting class conflict. It also accuses him of creating a website in the name of the Hathras victim.

According to his wife, Kappan is innocent and is only paying the price for speaking out against the government. “My husband has not committed any crime, I am sure about that,” she says. “They are using UAPA so that no journalist writes against the government again.”

Kappan remains in jail while prosecutors decide precisely how to frame the charges against him from the 5,000-page charge sheet prepared by the police. A lower court in Uttar Pradesh has taken up the case but that’s as far as proceedings have got and, whatever the decision on his case ends up being, Kappan faces the certainty of a lengthy struggle in India’s notoriously ponderous judicial system.

His wife said their request simply for the full charge sheet to be handed to their defence team had been stuck pending in court for over three months.

“It is our fundamental right to have a copy of the charge sheet. Without it in hand, how do we know what exactly is the case that the state is building against our client?” asked Mathews.

The hardest part of the struggle for Raihanath was the first one and a half months after her husband’s arrest, she says, when “we did not have any information”.

“Even the lawyer was not allowed to talk to him. I did not know if he was dead or alive,” she says. “It was only after we approached the Supreme Court, and the court sent a notice to the UP government that we were allowed to talk to him.

“I didn’t sleep in the beginning,” she says. “I would sit and cry for hours. My children would ask me constantly why their father can’t come home. But I had to pick myself up.” The couple’s three children - two boys and a girl - are aged 18, 13 and 8 respectively.

While the delay was “inexplicable”, she says, it was during this time that Raihanath also received a boost from the Keralan journalist community, which rallied around behind her husband.

The Kerala Union of Working Journalists (KUWJ), of which Kappan is a member, filed a habeas corpus plea in Supreme Court the day after his arrest, and to this day continues to organise rallies to raise awareness of the case. This includes protests in several cities including Delhi, organised in collaboration with the Press Council of India on the 5 October anniversary of the arrest.

In its statement condemning Kappan’s arrest last year, the Press Council of India accused the UP government of tapping the phones of journalists covering the Hathras gang-rape case and other “direct interference with the professional work of journalists”, what it described as a “blatant infringement” of freedom of speech under India’s constitution. The World Press Freedom Index 2021 ranks India 142nd out of 180 countries.

The KUWJ last week filed a contempt petition in the Supreme Court against the UP authorities, saying their “inaction” represented both a “threat to the life of the accused” and a “threat to the rule of law”.

The petition also drew attention to Kappan’s ill health, saying that despite a court order directing he be treated in a Delhi hospital he was returned to jail within a week of testing Covid positive in May. It said he suffers high sugar levels and severe dental problems, describing the journalist as “sick, demoralised and in severe pain due to lack of medical attention”.

The Independent reached out to Uttar Pradesh’s Prashant Kumar, additional director general of police for law and order, via phone and email, but did not receive a response prior to publication.

Despite the legal hurdles still ahead, Raihanath says she has not lost hope. “My husband has not committed any crime, I am sure about that as truth is on my side.”

Married at the age of 19, when she was training to be a lab technician, Raihanath had decided not to pursue a career and look after her family instead.

They were wholly dependent on Kappan’s income of Rs 25,000 (less than £250) a month. Without him around, friends and family are assisting the Kappans financially.

“Now when I look back I think I should have finished my studies and got a job,” Raihanath says.

The last year has seen her life change from being an ordinary homemaker to a woman fighting the state for justice - while still managing a household. Raihanath says her days are exhausting but she “has no option of resting” and is determined to fight till the end.

“It is my mission to get him released. Even though I am an ordinary woman I have the conviction that I must speak against this grave wrong. It’s not just about me but many others like me,” she says. “I am not just Siddique’s wife, he is also my best friend. If I don’t fight, who will?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments