Why did Russia try to assassinate Sergei Skripal – and why use novichok?

Novichok attack, 2018: Kim Sengupta recalls the attempt on the lives of the former Russian military officer and his daughter, and says there are still questions to be answered

The attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia was an extraordinary, shocking, and at many levels, inexplicable, act the impact of which continues to have grave implications in international relations. It was the first time a nerve agent had been used in a European city since the Second World War. Salisbury, a tranquil and quintessentially English cathedral city, seemed a particularly incongruous and surprising setting for a murder mission linked to the dark world of espionage.

I was abroad at a conference on nuclear proliferation when the news broke that a father and daughter had been found poisoned and unconscious on a park bench, and that the Russian state was the suspect behind the attack. Novichok and not nuclear weapons had become the lethal WMD threat to Britain for the moment, a matter of huge concern. But nothing about the current lives of the Skripals pointed to why they should be targetted for elimination in such a brutal way.

Sergei Skripal had been a member of the GRU, the Russian military intelligence service, and had in the past sold secrets to the British and the west. But he had been freed as part of a spy-swap eight years previously, was not known to be actively involved any longer in the intelligence field, and felt secure enough to continue living under his own identity. There was no evidence of Yulia ever being involved in her father’s line of business and nothing in her background suggested she had incurred such vicious enmity. To add to the confusion, other western agents – people the Russians would also consider to be traitors and who were swapped along with Skripal – had continued to live openly without being harmed and continue to do so now.

In my round of calls to try to put together a picture of Sergei Skripal I telephoned Marina Litvinenko, someone who knew all about Kremlin vengeance. Her husband Alexander had died from radioactive poisoning in London in 2006. A public inquiry into the death concluded that Vladimir Putin “probably” sanctioned the killing. Alexander Litvinenko, however, had been a vociferous critic of the Russian president and worked with his political opponents in exile. This was not the case, it seemed, with Sergei Skripal. Mrs Litvinenko pondered over the questions many of us were asking. “They had done the spy swap and that was the end of the matter. He thought he could live a normal life. He was not a defector, he was not attacking Putin, and we never saw him engage much in politics, so why should this happen to him?” she asked.

Theresa May’s government, while charging Moscow with the poisoning, had not at that stage provided proof of culpability. Jeremy Corbyn, who had asked for further evidence, was attacked as unpatriotic and a traitor by the Tories and the right-wing media. This was unfair. Demands to accept intelligence as true simply because the government says it is reminded me of reporting from Iraq in the run up to the invasion in 2003 when writing that much of the "dodgy dossier'’ did not stand up to scrutiny on the ground and led to instant vilification from Downing Street. I wrote a piece recounting the Iraq experience and suggested that the claim of Moscow’s hand may be true, but May and her ministers needed to provide more information. Many among the readers agreed that more proof was needed; others accused me of being a Russian stooge and a traitor.

In the ensuing days and weeks, when speaking to security officials, British and foreign, including some former members of the Kremlin, the intelligence community suggested that there was indeed Russian involvement. But it remained unclear as to who exactly had ordered the hit or why they had done so.

The British government kicked out 23 Russian diplomats. More than 20 other allied states also carried expulsions, the US the largest number with 60. Donald Trump, however, was reported to be furious, later claiming he had been duped by his officials into sanctioning many. There were jokes in security and journalistic circles was that the US president, allegedly the Muscovian candidate for the White House, was reacting to being told-off by his own agent handler in the Kremlin.

Information, meanwhile, was being gathered steadily. Sifting through acres of CCTV footage, the police and the security and intelligence services identified two Russians who had flown in from Moscow to London’s Gatwick airport and visited Salisbury twice during the weekend in which the Skripals were poisoned. The men, travelling under the names of Ruslan Boshirov and Alexander Petrov, on Russian passports and valid visas, had stayed at a low-budget hotel in Bow, in east London. Minute traces were found there of novichok, which had been produced in former Soviet laboratories.

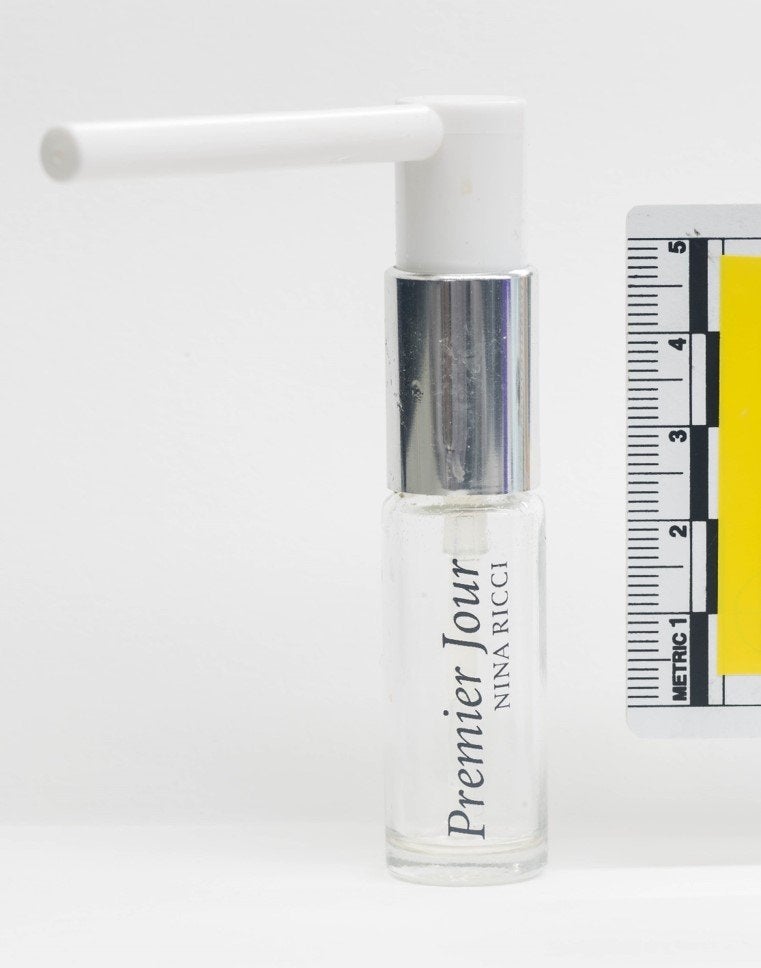

The Skripals survived the attempt to murder them. But three months later there was a death from novichok in Amesbury, a town close to Salisbury. Dawn Sturgess was given a bottle of Nina Ricci perfume by her boyfriend, Charlie Rowley, which she had sprayed on to her wrist. The bottle, containing the nerve agent, had been discarded by the two Russians as they left for the journey back to London.

Throughout all this the Putin government had been loudly denying any involvement in the Salisbury attack and claiming it was being framed. Alexander Yakovenko, Moscow’s ambassador to London, held a series of long press briefings, of up to a hundred journalists, at his residence with videos and graphs to press his country’s case. But then the Russians scored a spectacular own goal. The men known as Boshirov and Petrov appeared on state TV channel to demonstrate their innocence. What followed was risible.

The pair claimed they had flown all the way from Moscow to England for a couple of days just to visit Salisbury because the city was apparently world famous. They trotted out descriptions of the cathedral which appeared to have been cribbed from Wikipedia.

The investigative website Bellingcat revealed first that Boshirov was really Colonel Anatoliy Chepiga, a holder of Russia’s highest state award

Boshirov and Petrov wanted to explain that they had to go to Salisbury twice because the first visit had to be cut short due to snow on the ground. Even if one was to believe that two men from Russia were unused to coping with snow, television footage showed there was very little of the stuff on that day.

The interview, increasingly surreal as it went on, ended with RT (formerly Russia Today ) presenter Margarita Simonyan asking them if the two men were gay: “ Speaking of straight men, all footage features you two together. What do you have in common that you spend so much time together?” The men declined to answer. Simonyan later tweeted: “I don’t know if they are gay or not. They’re so stylish, as far as I could tell – with their beards and haircuts, tight pants.” She implied they may well have been gay because “they didn’t come on to me”.

That was the only reference to Petrov and Boshirov’s background. But the men’s TV appearance helped greatly in the search for their true identity. The investigative website Bellingcat revealed first that Boshirov was really Colonel Anatoliy Chepiga, a holder of Russia’s highest state award, and then that Petrov was Alexander Mishkin, also of the GRU.

A slew of further details about Russian intelligence activities in Europe emerged after this. Then came a failed GRU operation in the Netherlands. The target of the team, on a cyberhacking mission, was the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in the Hague, which was about to release the results of its investigations into the Skripal case.

I don’t know if they are gay or not. They’re so stylish, as far as I could tell – with their beards and haircuts, tight pants

Searches of the GRU officers’ phones and electronic devices by Dutch investigators revealed that one of them, Evgeni Serebriakov, had travelled to Kuala Lumpur when authorities there were investigating the shooting down of the Malaysian Airliner MH17 in eastern Ukraine in the summer of 2014. The same person had also, it showed, been to Lausanne with the alleged aim of hacking into the data system of Wada, the World Anti-Doping Agency, then probing drug abuse among Russian sportsmen and sportswomen, and infect it with malware.

The phones of the arrested officers also traced them back to the GRU headquarters in Moscow. One had a photocopy of a taxi receipt from the headquarters to the airport (842 roubles) needed, presumably, to claim expenses. Another had a receipt for batteries bought in Hague for their secret equipment. The performance of Russian intelligence was remarkably poor in Salisbury and its aftermath. It was a strange failure for the services, which has had a proud history of notable past successes and had, more recently, carried out sleek operations aimed at elections in foreign states including the US.

The performance of Petrov and Borishov on TV were lamentable. A former British intelligence official I met at at the time reflected on slipping standards. He recalled how it had been impossible to break Kim Philby in repeated questioning sessions, so good were his counter-interrogation techniques. It was fascinating to hear how Russia’s master spy deflected questions in the grillings from MI5 and MI6.

Philby, who had joined the Russians after witnessing Nazi atrocities in occupied Europe, had risen to the highest ranks of MI6 during decades in the service and had been stationed in Washington in a key post liaising with the CIA. The man who did massive damage to the west in the intelligence conflicts of the Cold War died of natural causes in his bed in Moscow. Skripal, on the other hand, who had, as far as we know, nothing much of intrinsic value to impart since his swap, only narrowly escaped death.

There have been many claims that Sergei Skripal was, in fact, engaged in important intelligence work and the attack was meant to silence him. These have been looked at exhaustively, but no persuasive evidence has emerged to back these accounts. The full explanation of why the Russian state tried to kill Sergei Skripal and his daughter, and used the extraordinary technique it did in attempting to do so, is yet to emerge.

Russian spy agency targetted Skripals

Kim Sengupta, 4 October 2018

The Russian military intelligence agency accused of the attempted assassination of former spy Sergei Skripal has carried out a swathe of attacks in the UK and abroad on political institutions, financial systems, transport networks and the media, according to the British government. This secret international cyberwar has included the targeting of the US presidential elections which brought Donald Trump to power, according to a new report from the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), as well the anti-doping watchdog in world sport.

The report follows the statement by Theresa May that Britain and allied countries will work together to expose the work of the GRU and the methods it uses. One of the two Russians accused by Britain of the attempted assassination of Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury, with the poison novichok, has been named as a GRU colonel. The Kremlin has denied the link, and denied any involvement in the poisoning of the former Russian spy.

This new document has been put together by the NCSC, working with other UK and European intelligence agencies, and the NSA and FBI in the United States. Although there were allegations of Russian culpability over many episodes of the organised hacking, investigations have shown that the GRU is the main perpetrators. The trail shows, say security officials, that the organisation has become the Kremlin’s chosen clandestine weapon in pursuing its geopolitical goals.

The GRU, according to the NCSC, is associated with a number of hacking groups whose names are used as “flags of convenience” including Fancy Bear, Sofacy, Pawnstorm, Sednit, CyberCaliphate, Cyber Berkut, Voodoo Bear, BlackEnergy Actors, Strontium, Tsar Team and Sandworm.

In April this year the NCSC, the FBI and the US Department of Homeland Security issued a joint alert about Russian cyber activity aimed at both the public sector, infrastructure and internet service providers. Ciaran Martin, head of the NCSC, said at the time: “Russia is our most capable hostile adversary in cyberspace so tackling them is a major priority. This is the first time that in attributing a cyberattack to Russia, the US and the UK have, at the same time, issued joint advice to industry about how to manage the risks from the attack. It marks an important step in our fight back against state-sponsored aggression in cyberspace.”

One of the biggest cyberattacks affecting this country took place in October last year when personal details of almost 700,000 UK nationals were accessed following the hacking of the US credit monitoring firm Equifax. At the same time attacks took place in Ukraine, a state with which Moscow is locked in confrontation, with the metro system in Kiev and Odessa airport hit, along with the synchronised use of malware in Bulgaria, Turkey, Japan and Russia itself.

In the summer of 2015, a British television company was targeted and information from multiple email accounts stolen. Four months earlier the French television station TV5Monde was taken off air when malicious software destroyed the network system. A group calling itself the Cyber Caliphate claimed responsibility at the time but the attack was traced back to the Russian hacking group APT 28, which has become better known as Fancy Bear, one of the GRU affiliates.

Two months after that, a cyberattack targeted the financial and energy sector in Ukraine, but soon spread further, affecting other European and also Russian businesses. The source of the malware was traced back, say British security officials, to the GRU. In September 2016, Wada (the World Anti-Doping Agency) was hacked, and data pertaining to athletes, including medical details, stolen. The breach was carried out by Fancy Bear. The information, which was disseminated on Fancy Bear’s website, involved 41 athletes from 13 countries, including six from the UK and 14 sports altogether.

This pattern of behaviour demonstrates their desire to operate without regard to international law

The hacking took place after the Russian branch of the organisation was suspended following revelations about a state-sponsored drugs programme. Russia is now about to be readmitted to the organisation, a move that has led to the resignation of a member of Wada’s committee and threats to do so from others. The allegations of Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election has hung over the Trump White House, with investigations being carried out by the special counsel, Robert Mueller, with the hacking of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) being one of key issues.

A vast amount of material, including Hilary Clinton’s emails, were made public, some of it through Julian Assange’s Wikileaks site. Twelve Russian nationals, allegedly members of the GRU, have been indicted over the cyberattack by Mueller. Two GRU teams, Units 26165 and 74455, both located in Moscow, allegedly carried out the campaign, beginning in early 2016, according to the indictment.

One of the intelligence officers, Senior Lt Aleksey Lukashev, used various online fake personas, including “Den Katenberg” and “Yuliana Martynova”, to craft “spearphishing” emails to gather the information. Captain Nikolay Kozachek, allegedly crafted the X-Agent malware used to hack the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and DNC networks in April 2016. Unit 74455, also known as the Main Centre for Special Technology, engineered the release of the stolen documents, according to the indictment.

In a statement in response to the NCSC’s report, the foreign secretary, Jeremy Hunt said: “The GRU’s actions are reckless and indiscriminate: they try to undermine and interfere in elections in other countries; they are even prepared to damage Russian companies and Russian citizens. This pattern of behaviour demonstrates their desire to operate without regard to international law or established norms and to do so with a feeling of impunity and without consequences. Our message is clear: together with our allies, we will expose and respond to the GRU’s attempts to undermine international stability.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments