Mysterious trails on Arctic seabed are from sponges on the move, say ‘surprised’ scientists

Sponges’ dubious categorisation as aquatic animals has been somewhat more validated by evidence they can move, writes Harry Cockburn

The sea sponge is a strange creature. Classed as an aquatic animal, but missing the usual features such as limbs, eyes, nervous systems, blood or organs, their animal credentials have remained somewhat thin on the ground - until now.

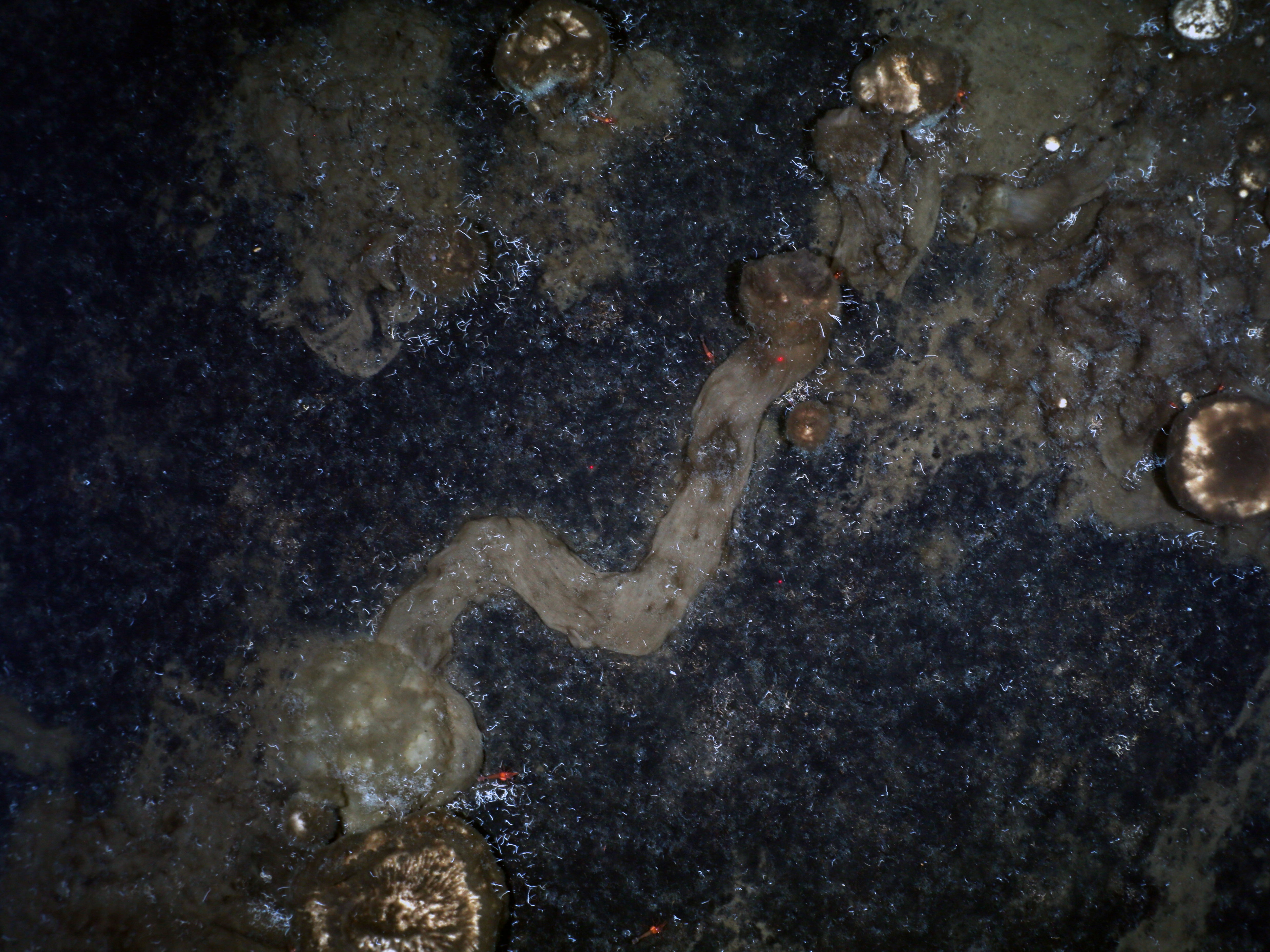

Though sponges are traditionally described as being entirely sessile - remaining in one place for their entire lives - scientists studying mysterious trails stretching several metres across the Arctic seafloor have found the first evidence of sponges being far more mobile than previously thought.

The trails, some of which were seen leading to living sponges, were found to be composed of sponge “spicules” - spike-like support elements in sponges - direct evidence of how the sponges had moved.

“We observed trails of densely interwoven spicules connected directly to the underside or lower flanks of sponge individuals, suggesting these trails are traces of motility of the sponges,” the researchers, led by Teresa Morganti of the Max Planck Institute of Marine Microbiology and Autun Purser of the Alfred Wegener Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, said in the study.

“This is the first time abundant sponge trails have been observed in situ and attributed to sponge mobility.”

The scientists said it looked as though the sponges had “crawled” into their current positions.

The researchers noted that sponges do have a “motile larval stage”, in which they move when they are immature, but most species are thought to become sessile as adults.

However, sponges have no specialised organs for moving around - they can react to external stimulation and move a little by contracting or expanding their bodies.

There also has been some recorded evidence of movement in sponges raised in the lab. In some cases, that movement involved remodeling their whole bodies.

But despite this, the research team said the new findings took them by surprise.

The discovery was made by studying video footage captured in 2016 by the research icebreaker Polarstern as it surveyed the submerged peaks of the permanently ice-covered Langseth Ridge.

A towed marine camera sled and a hybrid remotely operated vehicle showed that the peaks of the ridge were covered by one of the densest communities of sponges that has ever been seen.

The researchers determined that the impressive sponge populations were composed primarily of large numbers of Geodia parva, G. hentscheli, and Stelletta rhaphidiophora individuals.

They said it is not clear, given the challenging environment, how the area supports such a vast community of sponges. But, even more intriguing were the numerous trails of sponge spicules.

Far from a rarity, the researchers saw trails in nearly 70 per cent of seafloor images that contained living sponges.

Those trails were several centimeters in height and up to many metres long, and often connected directly to living sponges.

The trails were seen in areas with lots of sponges, as well as in more sparsely populated areas.

The researchers said they also often seemed to be in areas with smaller, juvenile sponges.

The researchers generated 3D models from the images and video to show the way the trails were interwoven with each other.

The models suggest sponges are not only able to move, but can sometimes change direction.

The team also noted that the movement is not merely a matter of gravity. In fact, the images suggest the sponges frequently travelled uphill.

They suggested the movement could be the sponges moving in order to get food, perhaps driven by the scarce Arctic resources.

“These features are all indicative of feeding and population density behavioural trends previously observed in encrusting sponges,” the researchers said.

“The extremely low primary productivity, sedimentation, and particle advection rates of the Langseth Ridge region overall result in some of the lowest standing stocks of benthic life; so potentially, this Arctic Geodia community relies on particulate and dissolved fractions from the degradation of old organic debris trapped within the spicule mat as additional food sources.

“We suggest that the mobility indicated here may be related to sponges searching for and feeding directly on the accumulated detrital matter trapped within the sponge spicule mat underlying the living sponges.”

They said it was also possible the movement could be related to reproduction or the dispersal of young sponges.

Further time-lapse imagery and other studies are needed to determine how fast and why the sponges make these unexpected moves, the researchers said.

The research is published in the journal Current Biology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments