What is impractical for schools now will not work in September

Editorial: Like the current quarantine plan, it is not a matter of a policy merely being unpopular or commercially damaging but of a policy that simply hasn’t been thought through

The plan to get all primary school pupils in England back into the classroom for a month before the summer holidays has been dropped.

Another coronavirus U-turn. “Quelle surprise!” as they might say in the beginners’ French lesson.

Even as things stand now, with the limited return for reception, year 1 and year 6, and the continuing classes for vulnerable children and those of key workers, there has been a sparse turnout. Only half of primaries are operational, and only about a quarter of eligible children are attending. In Scotland and Northern Ireland most primary age pupils are not due to go back until August and September respectively. In Wales a more limited scheme starts at the end of this month.

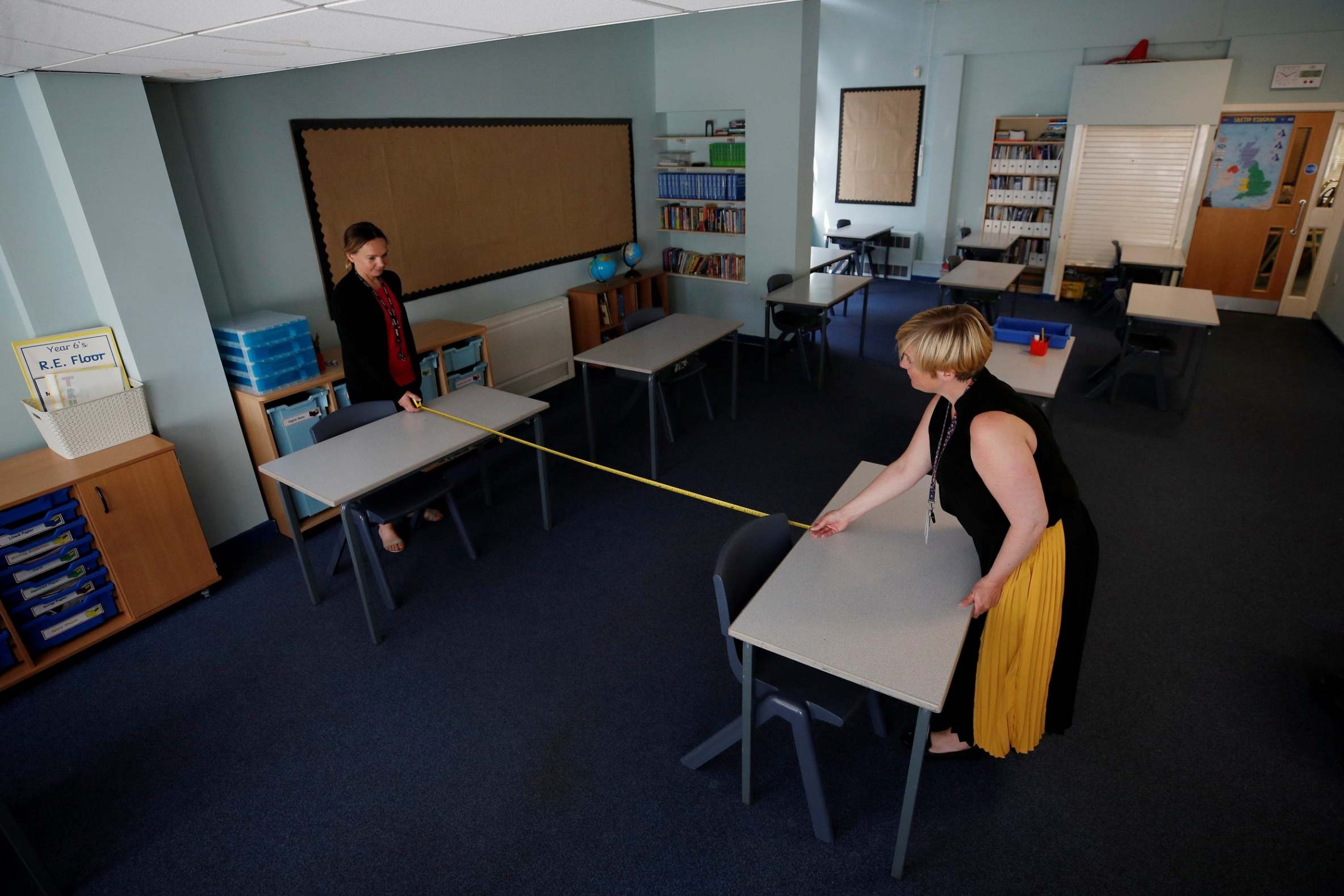

In truth the government’s sums never added up. Social-distancing rules necessitated radically smaller class sizes of about 15 and thus a huge increase in the space required to accommodate them. The room wasn’t there. So even if it was entirely safe for the children to return, some way had been discovered of preventing little ones breaking the two-metre rule and if all the parents had been supportive – which they were not – it was never a practical proposition.

Like the current quarantine plan, it is not a matter of a policy merely being unpopular or commercially damaging but of a policy that simply hasn’t been thought through and remains impractical. Even less comprehensibly, ministers have pressed on with the primary school plan despite loud warnings from teachers and local authorities, just as they ignored the airlines and the travel industry on the new and unenforceable quarantine rules.

It may be dawning on the government – and indeed the devolved administrations – that what is impractical today will not magically become practical in September. Only if coronavirus is virtually eradicated would the current proposals become practical.

A more imaginative approach is needed to deal with this unprecedented situation, from central government, local councils, the unions and parents alike. Could other spaces such as places of worship be “borrowed”? Could well-endowed, fee-paying schools cooperate on solutions? Why not revisit the arcane practice of overlong summer holidays, now that British children aren’t expected to help get the harvest in? Could different schools stagger their terms, given they are currently empty for the same large parts of the year? Can remote or digital learning become a more permanent feature of education, or at least until Covid-19 disappears?

It is all obviously made more difficult to achieve and plan for while no one knows if or when a vaccine will be discovered, and there is still not enough known about transmission of the virus among and by children. Yet the educational gap between social classes and ethnic groups widens with every skipped lesson, field trip and afternoon on the playing fields.

A U-turn may be forgivable if it gives way to a more sustainable policy for schools – but we are yet to see it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments