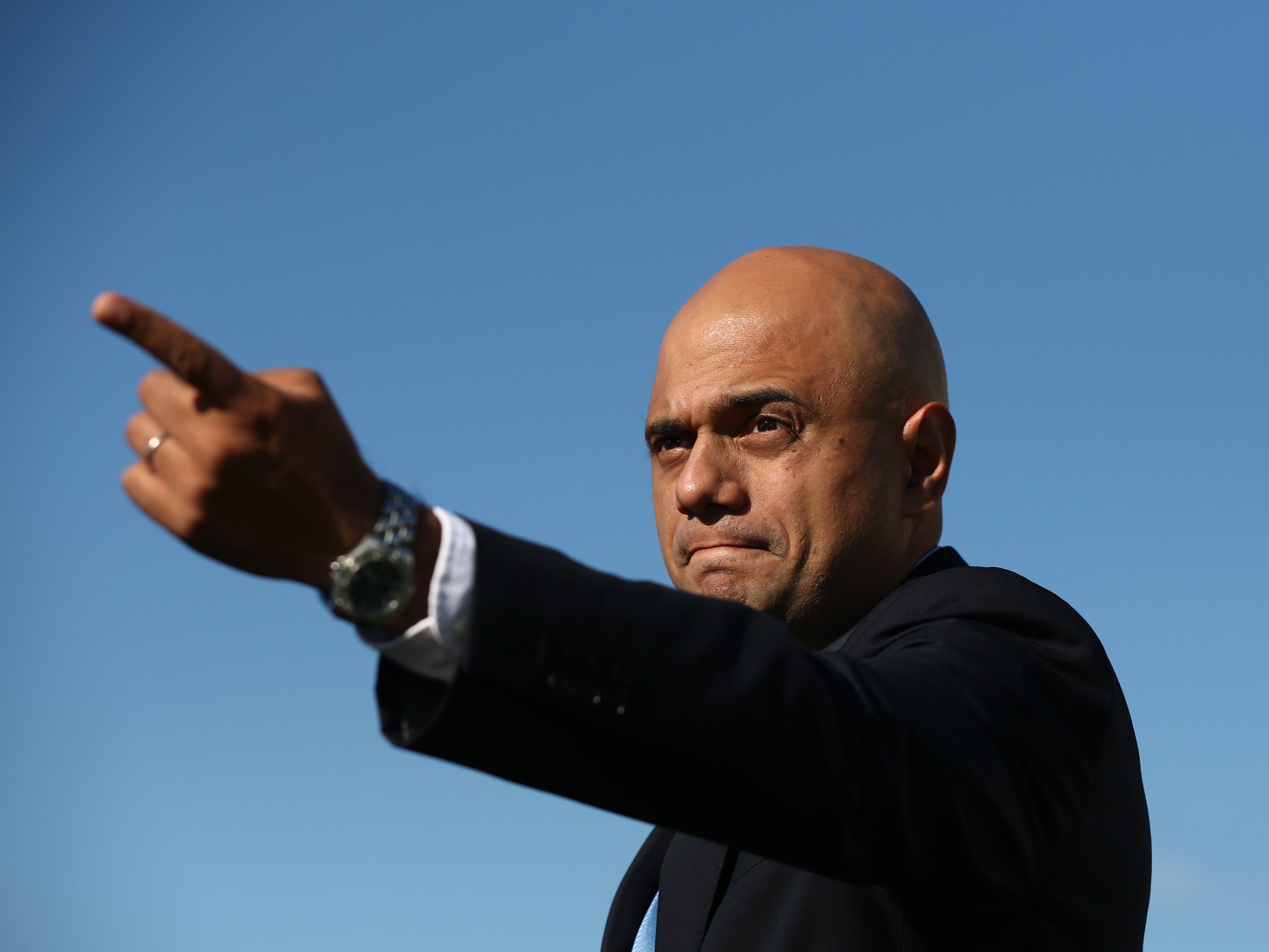

Is Sajid Javid doomed to repeat the mistakes of Matt Hancock?

It wasn’t long ago that Javid told the nation not to ‘cower’ from Covid. Now questions are being asked about whether he’s the right man for the job. Sean O’Grady takes a look back at the life and career of one of the most prominent ministers of the last decade

In what seemed to be a hastily-convened press conference last week the new-ish health and social care secretary, Sajid Javid, had a slightly haunted look about him, as well he might. He is far too proud, ambitious and decent (you’d like to think) a man to want to be yet another fall-guy for Boris Johnson’s failings as a leader, let alone responsible for thousands of people losing their lives unnecessarily in a pandemic that refuses to go away. Yet that is precisely where he is headed. Javid knows that Matt Hancock’s political career was doomed because of the government’s chaotic response to Covid, even before his celebrated last-dance-at-the-school-disco style smooch in his office; remember the infamous leaked WhatsApp message long before that from Johnson to Dominic Cummings that he, Hancock, was “f****** hopeless”?

In that context, Javid now surely realises too that another spike in cases could soon enough translate into the kind of “unsustainable pressure” that would see ambulances full of severe Covid and flu cases queuing up outside A&E, and the families of cancer patients going on TV to blame him for their loved one’s late diagnosis and delayed treatment. The public officials and the scientists have already no doubt told him that it’d be a good idea to ask people to wear masks and work at home for a bit; and you strongly suspect that Johnson, senselessly boosterish as ever, has told Javid “not yet” and Javid, a cool customer and not in a rush to impose new restrictions, may have been content to go along with it.

In any case it all made for a curious official briefing on Monday afternoon. So there the health secretary found himself, at the Downing Street podium, flanked by senior advisers and surrounded by the media, and announcing not very much at all. He must surely fear having to stand up there again in a month or two telling the nation that he is about to immediately impose emergency lockdown measures to deal with an entirely predictable and predicted winter health crisis – comprising the backlog, Covid, flu, other seasonal respiratory diseases and a shortage of carers, all known about weeks ago. No wonder Sage is organising preliminary “policy work” for new rules. For yet another mess-up it would be Javid who will carry the can.

It doesn’t really help that Javid was recruited to replace Hancock because he was judged to be a bit of a lockdown sceptic (Hancock, by contrast, was being as cautious in public policy as he was reckless in his private life). If it all goes wrong – hardly unprecedented – Johnson will jettison Javid regardless in order to escape the blame and Javid, like Hancock, Gavin Williamson, Robert Jenrick, Dominic Raab and others, will find himself sliding down the greasy pole.

Mind you, you wouldn’t want to bet against Javid, who has proved himself a resilient and resourceful politician, and someone who seems to have a highly developed sense of pragmatism. At the moment, even with the floundering vaccine drive and a hard-pressed NHS, and only three months into the job, he can’t yet risk making threats about quitting just because the prime minister is too much of a gambler, or too weak, to implement “Plan B”. It would destabilise an already delicate situation and badly damage the government as it moves into the critical winter crisis.

His party would not thank Javid for that, even if he wanted to do it. He may also be waiting for the weight of evidence and scientific advice to become irresistible before pushing for action. He’d be wise not to wait too long, though he is quoted as saying “I’m entitled not to listen to Sage”, the expert committee. He is also facing the threat of strike action by GPs because he chose to pick a fight with them over face-to-face consultations, and upset them by suggesting he’d “name and shame” laggards.

In one of the cringe moments during the 2019 Conservative leadership debates, the candidates were asked about their greatest weaknesses. Some replied, David Brent style, that they were, if anything, too virtuous (though none echoed Keith from Accounts and said “eczema”). Javid owned up to being ”too stubborn”, citing his refusal to give in to his children asking him to get a puppy for 10 years. Eventually, by the way, the cavapoo, Bailey, arrived and was pressed into service as a loveable political prop for his master. Lesson learned, though, and Javid now says he sees the attractions of pragmatism and “settling for 60 per cent rather than zero per cent”. He’s learned this wisdom over what is now a long, varied and mostly competent ministerial career. Perhaps also Javid is mimicking his hero, the legendarily determined Margaret Thatcher, who also displayed tactical flexibility. In any case, Javid may learn the hard way that it’s usually unwise to ignore medical advice.

He is something of a survivor, then, as well as a rising star. Having entered parliament in 2010 as MP for the very safe Conservative seat of Bromsgrove, he was given his first job by David Cameron in 2011, and a year later became one of the tight-knit Treasury team around George Osborne. He was elevated to the cabinet in 2014, as culture secretary, followed by stints running Business, Communities, Justice and the Home Office under Cameron and Theresa May. When Johnson become party leader and prime minister in 2019 he made Javid chancellor of the exchequer, recognising Javid’s respectable showing in the leadership contest (coming in fourth), his Treasury experience, and his long two-decade career as an investment banker (which has left him richer than most of his colleagues). He was affectionately referred to by Johnson as “The Saj”, and The Saj was usefully friendly with Carrie Symonds. She’d worked for him before as a special adviser, and once gave him a birthday card featuring Javid’s head as an avocado. But the fun was not to last.

He can’t yet risk making threats about quitting just because the prime minister is too much of a gambler, or too weak, to implement ‘Plan B’

The first sign of trouble was when, shortly, after his appointment, Johnson’s Svengali, Dominic Cummings, unceremoniously fired Javid’s special adviser, Sonia Khan, without the chancellor’s knowledge, let alone approval. Furious, Javid put up with it, but it was a harbinger of doom. Post election, in February 2020, Johnson and Cummings moved to, effectively, take over the Treasury and demanded that Javid sack his remaining advisers and generally do what No 10 wanted. This time, Javid was stubborn and he quit, stating that “no self-respecting minister” could tolerate that treatment, and that the merger of No 10 and 11 was a bad idea. Javid’s junior minister, Rishi Sunak, took over, supposedly more sympathetic to the Johnson-Cummings plan. In crude terms, the idea was that the fussy Treasury and its narrow financial outlook would no longer stand in the way of the big, free-spending visions of the new populist order. It marked the high point of Cummings’ power.

So Javid returned to the backbenches, an unfamiliar world, though comforted by a £150,000-a-year fee for consultancy from an investment bank. He was careful, despite commenting on the “comings and goings”, not to burn his bridges with Johnson, and Johnson left the door open for a return, as we see. The curious thing was that the much-feared constitutional revolution never happened, and the Treasury pretty much does what it always did – to the extent that Sunak could soon tell the media that he’d chopped up the prime minister’s metaphorical credit card. In the version of events spun by Cummings later, the whole enterprise was dreamt up by him, to “fool” Johnson into sacking Javid, who Cummings disdained as a mere “bog standard” old-school minister, little more than a creature of convention and patronage and a broken political system.

We all know what happened next. Cummings disgraced himself in lockdown, “Princess Nut Nut” Carrie won her turf war with Classic Dom, and Javid was recalled to the top table, in what was now a top job, as soon as Hancock fell. In the tweet sent by Cummings:

“So Carrie appoints Saj! NB If I hadn't tricked PM into firing Saj, we'd have had a HMT (Treasury) with useless SoS/spads, no furlough scheme, total chaos instead of JOINT 10/11 team which was a big success. Saj = bog standard = chasing headlines + failing = awful for NHS. Need #RegimeChange.”

At the Department of Health, Javid is running his sixth government department, and facing by far his toughest challenge.

He is, though, no stranger to adversity, and is fond of telling stories about his tough life as the son of a Pakistani bus driver who came to Britain with £1 in his pocket and a mother who, though “one of the cleverest people I know”, could not read or write. In fact, his father and the family gave up even more to risk settling in the UK – at the direct invitation of employers desperate for migrant labour. His grandfather mortgaged the family home to pay the airfare, and the £1 was the change. His is an almost perfect backstory. He grew up in a terraced house in Rochdale and later on in a not especially nice area of Bristol. In the late 1970s aged six or seven, he was roughed up by the local National Front skinheads, who’d spit on and throw stones at him and his brothers – it was “frightening” and made him “angry” eventually, but “we got used to it”. Being called the P-word was routine, but he fought back when he could, punching the school bully (they met many years later by chance and the ex-skin apologised to the future cabinet minister).

The story of the Javid family is painted as a sort of Thatcherite parable – mum and dad working hard, saving up money and overcoming prejudice to run a retail business, and the kids encouraged to do better than they had: his late father Abdul apparently remarked to them: “I haven’t come all this way to see my children fail”. The brothers also all did well for themselves: Basit, or Bas, is a deputy assistant commissioner with the Metropolitan police; Atif is a property developer; Khalistan works in finance; and the eldest, Tariq, ran a retail business before sadly drowning in 2018.

You can sense the pain over the decades that the Javid family, like so many others – ‘outsiders’ – from all manner of backgrounds have experienced from casual, unthinking racism

It was his dad watching BBC News every evening that awakened little Sajid to current affairs, politics and this strange personality called Mrs Thatcher. He says he was in fact a “Thatcherite” before he understood what a Conservative was. Javid Sr voted Conservative for the first time in 1979, and Javid Jr became steadily more Thatcherite as he reached maturity in the 1980s boom time in the city, eventually earning some £3m a year as a senior investment banker working in London, New York, Singapore and sealing deals in emerging markets such as Mexico.

Maybe, like Johnson, he remembers Gordon Gecko’s creed of the time – Greed is Good. By the time he faced his five Oxbridge-educated rivals in the 2019 leadership contest – two of them Old Etonians – he was the only one who’d gone to a comp, and could be satisfied that he came from humble beginnings to end up at least as wealthy as most of them. And Michael Gove, Johnson, Dominic Raab, Rory Stewart and Jeremy Hunt had been told when they were looking for a seat that they were unsuitable because of their religion. Javid thinks anyone with the ability can get to No 10, including him.

There were striking parallels, often alluded to by British Asians, in these simple Thatcherite values mirroring across seemingly different cultures, and indeed the Javids were more like the Thatchers than most, given that Thatcher’s father was famously a shopkeeper and her mother, like Javid’s, a part-time seamstress, staying up late at night running up blouses and skirts for sale. Javid once told this anecdote of his dad’s Pakistani Thatcherism with a twist. “He ran a market stall flogging clothes that my mum put together on the kitchen table and he was always looking for sites with less competition.

In due course, the young Javid, as a politician on the make, was to meet his idol Thatcher. In his account, having been introduced to her, the Iron Lady repeated his name twice, grasped his hand, and ignored his attempt at small-talk before declaring: “You will protect this isle”. “Yes! Yes!” the disciple replied.

So, then, what kind of Conservative is Javid? Is it that Javid’s simply grown up and learned not to “allow the perfect to be the enemy of the good” as he claims, or whether he is a bit of a political chameleon, adjusting himself and his outlook to the mood of the times. Perhaps, in fact, that very flexibility makes him an ideal Tory leader, given that the party has always adapted to survive.

On the one hand there seems no reason to doubt that he has been moved by some of the things he encountered in his youth and later as a cabinet minister. He had to clear up the Windrush scandal at the Home Office, bequeathed to him by May and Amber Rudd – “I was really concerned when I first started hearing and reading about some of the issues. It immediately impacted me. I’m a second-generation migrant. My parents came to this country ... just like the Windrush generation.

“They came to this country after the Second World War to help rebuild it, they came from Commonwealth countries, they were asked to come in to [do] work that some people would describe as unattractive – my dad worked in a cotton mill, he worked as a bus driver.

“When I heard about the Windrush issue I thought, ‘That could be my mum… it could be my dad… it could be my uncle… it could be me.

Equally upsetting was the Grenfell disaster, which he found himself confronted with as housing and communities secretary, where so many of the families had, like his, come from abroad. He has in more recent years, and in a very un-Thatcherite way, admitted that, as well as a strong family and enterprise, he was also the beneficiary and product of good public services – the school and college of either education he went to before Exeter University, and the libraries he studied in when home was too noisy.

It’s striking, though, how easily Javid’s political development has evolved to match the outlook of successive leaders – austere, mediated Thatcherism under Cameron and Osborne, a more generous attitude to the public sector under May, and then the transition from EU Remainer to new-born populist Brexiteer under Johnson, rejecting “spreadsheet politics” and embracing levelling up along the way. He even backed Johnson’s unlawful attempts to suspend parliament in 2019, having solemnly pledged only months before never to put Brexit before parliamentary democracy, when he was running for the leadership. In that campaign, too, he sounded a sober warning about the dangers of strident populism – yet now cheerfully joins in with Johnson’s never-ending and deeply divisive culture wars, with the consequences we all know about. It is plain who Javid had in mind when, before he joined Team Boris, he told the television audience only two years ago:

“I do feel today there is too much division in our society. We’ve talked about whether someone is Remain or Leave, North or South, Urban or Rural…Whatever happens, I think this is the number one thing in our country today, if we are staying together as a cohesive society, and I think it is incumbent on all politicians, especially with what we see around the world in the US or Italy, and others, where you have politicians that want to feed off anger and feed off division, that we as Conservatives always look for the best in people and try to bring them together.”

Oh, well.

Javid justifiably makes much of his back story and Muslim heritage, but as is the current Tory orthodoxy, refuses to be defined by it. On a personal level he fell in love with his wife, a church-going Christian, when he was 18 and they were both doing summer jobs at an insurance office in Bristol. They wed against the advice of some in his own community, and leave it to their four children to decide which faith, if any, they wish to follow. Javid has claimed that “we have become the most successful multiracial democracy in the world”. Even so, he did manage to extract a public promise from Johnson and the others to conduct an enquiry into Islamophobia by springing it on them during one of their TV debates, though in the end not that much came from the Singh Inquiry. Javid has spent his time as a minister fighting far-right and Islamophobic extremism, antisemitism and other racism with equal fervour, and has been less ready than others to ridicule taking the knee and Black Lives Matter. He seems highly conscious of the barriers he and his family once had to overcome. His father wasn’t allowed to graduate from being a bus conductor to a driver “because the union had a rule that all drivers had to be white. There was an informal colour bar. So he kept trying, and eventually he did become a driver.”

Javid says his father had to pick the application up from the floor where the clerk had chucked it contemptuously – but Abdul told them that he knew what they were doing was illegal and he knew his rights. So in fact his success was down to legislation passed by a Labour government as well as his own persistence and innate instinct for getting on.

You can sense the pain over the decades that the Javid family, like so many others – “outsiders” – from all manner of backgrounds have experienced from casual, unthinking racism, institutional or otherwise in Britain. By his own witness it was painful and humiliating – and never-ending. He gets plenty of abuse even now. It must have been galling, at best, to discover that he, as home secretary, had not been invited to the grand banquet given for president Donald Trump – the only one of his senior colleagues not to when the likes of Gove got a ticket, and he called it “odd”. Still, Javid seems content to sit in a cabinet led by the man who likened Muslim women to letterboxes and bank robbers. For now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments