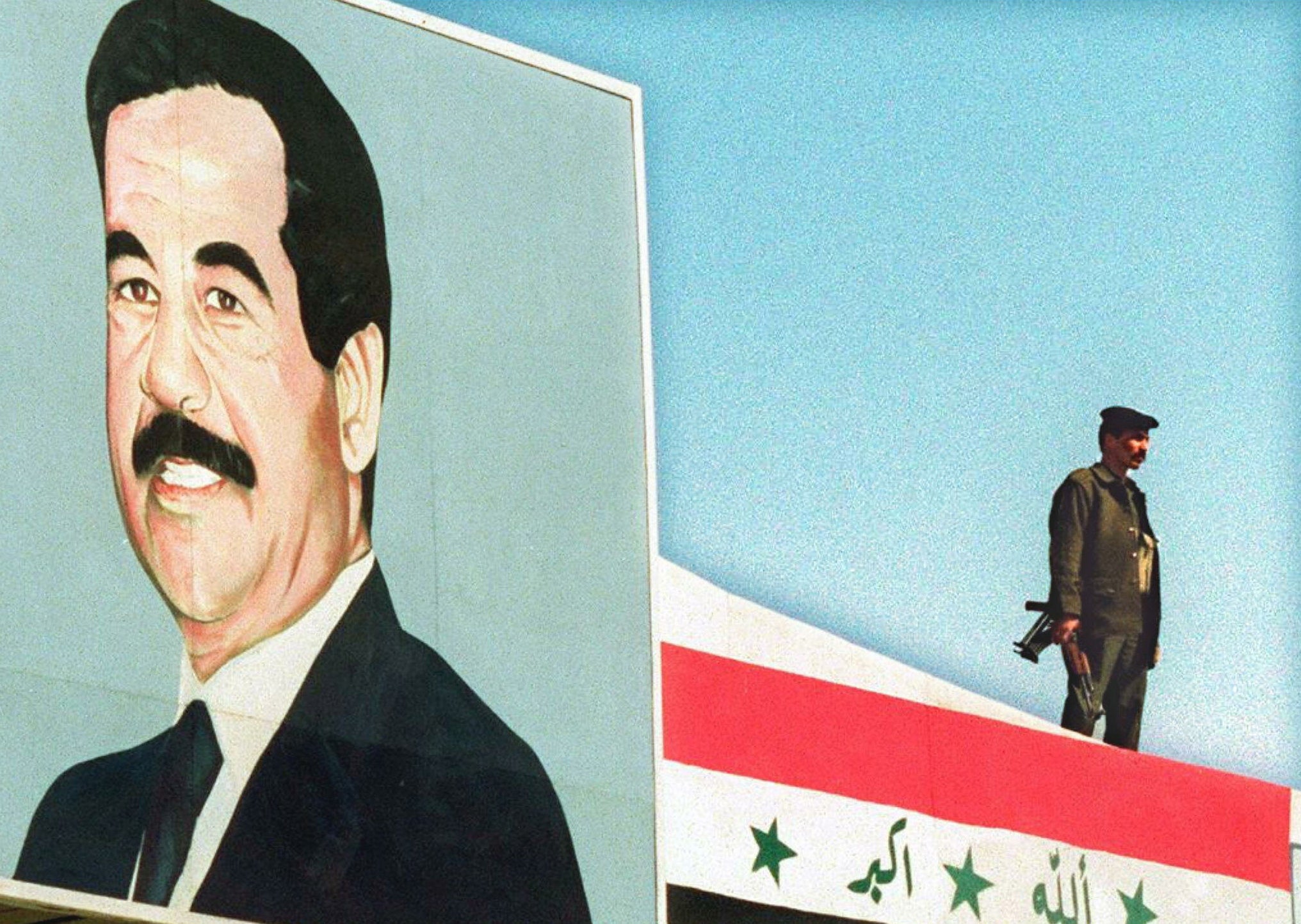

Iraq’s chamber of horrors: An encounter with Saddam’s former chief scientific adviser

December 1997: Robert Fisk meets Dr Hossein Shahristani, a survivor of Saddam Hussein’s regime of systematic torture

When I ask Dr Hossein Shahristani what he thinks of Saddam Hussein, he recalls at once the day in 1979 when the Iraqi dictator marched into the offices of the Atomic Energy Organisation in Baghdad. When Saddam ordered his scientists to start work on nuclear weapons, Shahristani – who was Saddam’s chief scientific adviser – protested that this would violate Iraq’s signature on the Non Proliferation Treaty.

A diminutive figure with frameless spectacles, his Canadian wife standing beside him in Islamic hijab, Shahristani turns to me in my grubby downtown Tehran hotel and bangs his finger into my chest, his words fierce and passionate – Saddam-like in their intensity. “Saddam pointed his finger at me like this, and he said: ‘You are a scientist; I am a politician. Do you know what politics is? I will tell you what politics is about: I take a decision. I tell people I am going to do the opposite, then I do something that surprises even me.’”

There was silence in the foyer of the hotel. Shahristani understood the message of his little story. Was this, I wondered, how Saddam invaded Iran a year later, or Kuwait a decade later, a sleepwalker following his own terrible destiny? Shahristani shrugged his shoulders. Within months, he was in the torture chambers of Iraq’s security police; he only escaped from his tormentors 11 years later, during Allied air raids on Baghdad. He tells his story dispassionately, in detail and it is one of horror and fear and terrible pain.

Dr Shahristani studied nuclear chemistry in Toronto where he met his future wife Bernice, who was to stay in Baghdad all those long years while her husband sat, mostly in solitary confinement, waiting for his executioners to arrive at his cell door. Saddam had been a frequent visitor to the Atomic Energy Organisation (AEO) and knew Shahristani well. And Shahristani thought he was important enough – safe enough – to protest to colleagues about the wave of executions and arrests among Iraq’s Shia Muslim community, to which he himself belonged. He had been especially shocked by the fate of a young man who was arrested on his honeymoon, accused of taking part in “religious activities” and terribly tortured. His crime was to be suspected of being a member of the Dawa party. “His family saw him later; his body had been filled with gas through the rectum. He was horribly swollen and had been beaten. They brought his young wife before him and threatened to rape her if he did not confess. Did he want them to rape his wife, he was asked? And he banged his head against the wall so fiercely that they say the wall shook.”

The young man was never seen again. And shortly after his complaint, Dr Shahristani nearly shared the same fate. “I thought I was crucial to their atomic energy programme, that they would not arrest me. I was wrong.” On 4 December 1979, a group of Iraqi security officers arrived at the AEO while the doctor was at a board meeting. “They asked: ‘Could we have a word with Dr Shahristani?’ They were very polite. But as I stepped outside, they put handcuffs on me, shoved me into a car and took me to security headquarters in Baghdad.”

The coffins would come in the afternoons. They would be in a queue on top of the cars. People were told in the morning their relatives were going to be executed, so they took the coffins and waited

He was taken straight to the office of Dr Fadel Baraq, the senior director of security (later executed on Saddam’s personal orders). “Baraq said that someone who’d been arrested had given my name as a contact,” Shahristani recalls. “I denied any involvement in politics, said I was a practising Muslim but had never taken part in subversive activities. Then they brought this man whom I knew, Jawad Zoubeidi, a building contractor – he had been so badly tortured I hardly recognised him. He said: ‘I know Dr Hossein; he comes to the mosque and takes part in religious activities.’ You see, for them – for the security police, ‘religious activities’ meant anti-government activities.

“Baraq said to me: ‘Better you tell us all or you’ll regret it.’ Then I was taken straight to the torture chamber in the basement, blindfolded and pushed down the stairs so that I fell down, and then I was carried into a room. My hands were pinioned behind my back and I was lifted up into the air by them. After a few minutes, the pain is so severe in your shoulders, the pain is unbearable.”

Baraq was present during the torture, calm and relaxed and at ease amid all the suffering. His men were experienced in the infliction of pain. “From the board room of the AEO to the torture chamber was less than an hour; yes, they are very efficient, the Iraqi security police.”

After he had been hanging for some minutes, the torturers produced electric cattle prods which they applied to Dr Shahristani’s genitals and other parts of his body. “When you break into a very cold sweat, it means you are about to faint, so they take you down and give you a short rest. You fall asleep for a few minutes. This went on day and night, day and night, for 22 days. Four of them did it to me, in shifts. Over and over, Baraq would be there saying: ‘Confess – tell us all you know.’ At one point, he said: ‘Look, Dr Hossein, I’ll tell you what your problem is – you think you are smart enough and we are stupid. Well, you may be smart in your own field but we know what we are doing – just tell us what you know and get this over.’”

Armed military intelligence personnel had moved into the Shahristani home, sharing it with Bernice and her son and daughter, Mohamed and Zahra. She waited each day for the terrible news. Once a month, she would visit Shahristani at the Abu Ghraib prison. Executions were performed on Sundays and Wednesdays. “The coffins would come in the afternoons,” Bernice says. “They would be in a queue on top of the cars. People were told in the morning their relatives were going to be executed, so they took the coffins and waited. One day, Mohamed asked me: ‘Is one of those boxes for Daddy?’”

When Bernice first saw her husband – 39 days after he was seized – she did not recognise him. “I recognised his jacket, then his trousers, then I realised it was him. I saw one tear coming down his face. I thought: ‘He’s going to be executed, that’s why they’ve brought me to see him.’” Dr Shahristani was in hell. He had seen other prisoners who had been burned on the genitals and scorched with red-hot irons on their stomachs. Several had holes drilled into their bones.

“One man had all his genitals totally burned off... They showed me a bath in which they had killed a leader of the Dawa party by dissolving him in sulphuric acid. One man I especially remember. He was in the Dawa and he was going to be executed but he was in my cell, laughing and joking with me. What courage! I said to him: ‘Before they take you away, let me be your executor. If I survive, I will do anything you want.’ And he just said: ‘There is nothing. It doesn’t matter. My death is not important.’ He was still smiling when they came for him. I will always remember that brave young man.”

Dr Shahristani’s Golgotha was interrupted for some months by a dream-like imprisonment in the palace of a murdered government minister where – amid fine food and television films – Saddam’s half-brother Barzan tried to persuade him to return to nuclear research. “He said to me: ‘We need an atomic bomb because this will give us a long arm to reshape the Middle East. I know what you can do and I am asking you to go back.’” Shahristani refused – and returned to Abu Ghraib.

His dramatic and successful escape probably requires a book. Befriended by a fellow Shia Muslim prisoner, he drove to freedom in a security police car – and dressed in police uniform – at the height of the 1991 US and British air raids on Baghdad. Joining his family in a Baghdad suburb, they drove north to Kirkuk where Dr Shahristani briefly participated in the Kurdish uprising, where he saw Saddam’s secret service men dead in the compound of their local headquarters. He was smuggled into Iran in the back of an old Toyota truck.

Today the couple lives in Tehran, where they run an Iraqi refugee aid foundation which is partly supported by the British Overseas Development Administration and the UN.

“The Iranians have been very kind, but this is not our home,” Dr Shahristani says. No, he has no nightmares, no bad dreams. Perhaps only a man of such hard, inflexible – almost frightening – determination could survive Saddam. “I knew I was doing the right thing,” he says. “I never regretted the stand I took.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments