Why are the Tories so obsessed with the union flag?

Apart from the far right’s efforts to steal it, and some occasional overuse by Tory eccentrics, the union flag has largely been apolitical. Not it would seem, for very much longer, writes Sean O’Grady

Tribal as people tend to be, the display, or not, of flags, banners and emblems tends to be a contentious affair, even in the most liberal of democracies and usually tolerant of populations. Even in states where the burning or other desecration of the flag is illegal, such as France, disrespect is sometimes shown as a gesture of political dissent or defiance. As with statues and historical monuments, flags have the power, often as not, to divide as well as to unite communities. When political parties attempt to appropriate a flag to themselves, the reaction among others can be especially severe.

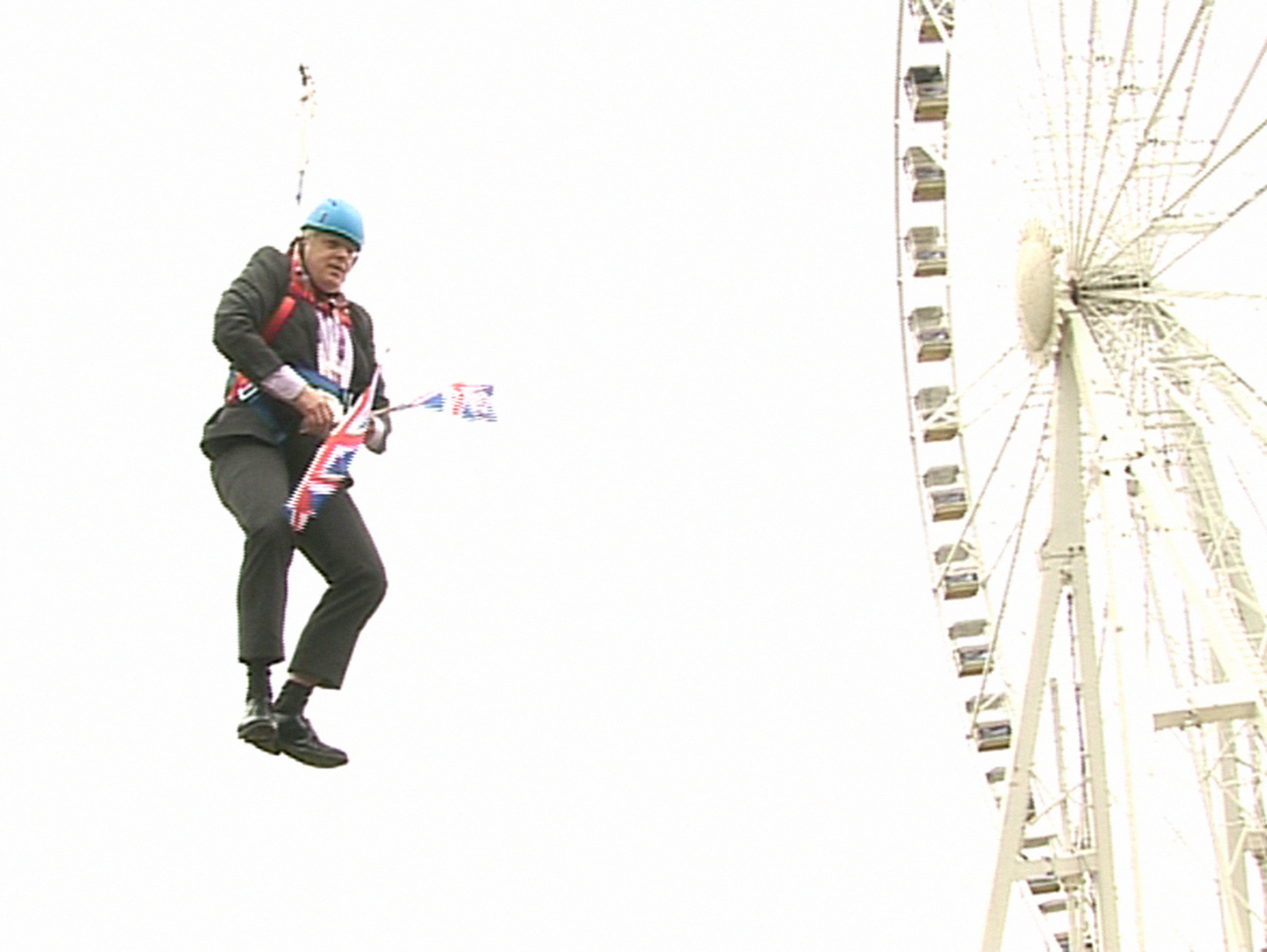

Such is the case with the sudden popularity of the union flag among British ministers and other Conservative politicians. In the past, the Tories, the party of empire, were happier than most to drape a union flag over a trestle table at a public meeting or decorate a manifesto with a few, to remind the voters of their opponents supposed and implied lack of patriotism. But it was a trick sparingly used, even by the likes of Margaret Thatcher, who once semi-jokingly draped a hanky over a model of a British Airways plane featuring one of its then new international ethnic designs, rather than the traditional red, white and blue. No longer. Cabinet ministers now seem to compete as to who can manage to jam the most and the biggest union flags into a Zoom call. When the communities secretary, Robert Jenrick, was gently teased about his union jack “rating” when he appeared on BBC Breakfast, the presenters, Naga Munchetty and Charlie Stayt, were publicly reprimanded by BBC management. A Tory backbencher even asked the BBC why it didn’t have more union flags in its annual review.

Read more:

The national flag, in other words, is becoming another front in Britain’s culture wars, and the battle is intensifying. The culture secretary, Oliver Dowden, has said he believes new rules concerning the flag will serve as a “proud reminder of our history and the ties that bind us”. The early indications are that it will be anything but.

Boris Johnson wants all UK government buildings to fly the flag all year round, rather than the current ration of saints days, royal birthdays and other special moments in national life. Local councils will be “encouraged to do so” perhaps in the knowledge that having to dispatch the police to tear down offending EU, rainbow or trans flags, for example, would be too politically explosive even for this administration. There is even a suggestion that planning permission would be required (presumably only applying to public authorities, but we cannot be sure) to fly the starry flag of the European Union – uniquely so, as there is no explicit ban on displaying the swastika, say, or the black flag of Isis. Even for Brexiteers it feels a little over the top, like the now-abandoned idea that the vials of Covid vaccine should be embellished with little union flags.

Of course Mr Johnson is not alone in his consciousness of the power of national symbols, and he has his match, not for the first time, in Nicola Sturgeon. It is fair to say that the union flag has been a rare sight anywhere in Scotland for some time, but now the first minister wishes to go further. Contrary to some reports she has not “banned” the flag anywhere, nor “replaced” it with the EU flag; but she has ruled that the flag is no longer flown on royal birthdays, while the European flag is now flown almost every day. Where the Scottish government has no jurisdiction, such as on UK government offices, then the union flag will be fluttering defiantly in the Scottish breeze, whatever the political weather.

The exception to the new UK edict is Northern Ireland, where culture wars are nothing new. Many decades ago it was against the law (effectively) in the province to display the Irish tricolour, and individuals and the RUC could be forceful in removing from windows and the like, acts that did little to foster cross-community understanding and by the 1960s contributed to the start of the Troubles. The Northern Ireland Flags and Emblems Act of 1954 was only abolished in 1987, and today politicians try to tiptoe around the usage of these powerful and sometimes provocative symbols, and they remain a bit of a “red flag” even after more than two decades of the peace process. The nearest thing Northern Ireland had to a flag, the banner with the red hand and the crown, was actually never official and was always regarded as a symbol of Protestant supremacy, just as the Irish flag was equated with the IRA. The experience is not a happy precedent for what the Johnson government seems to have planned for the mainland. The way the union flag was in the past appropriated by the National Front and the BNP, as the English flag of St George are also unhappy reminders of the dangers of politicisation of what should be uncontroversial emblems.

Indeed, the spirit and possibly the letter of what Mr Johnson is seeking to do is at odds with other legislation which was aimed at taking the flak out of the flag. The Public Order Act of 1986 and the Terrorism Act 2000 are masterful in deterring provocative and political usage of flags, something that is now being proposed as a matter of government policy – because people bitterly opposed to the government and the Conservatives will come to see it as a political symbol rather than a national one, which is counter to the avowed aim.

For most of the past few hundred years the union flag has always been part of the British national consciousness, and sometimes associated with freedom and democracy, and the defeat of fascism; but, it is fair to add, at other times the flag accompanied imperial conquest and oppression. Either way within the UK, aside from jubilees, royal weddings, VE Day, and other shared national moments it was mostly unobtrusive, with no taint of compulsion attached to it. Monarchs and prime minister, still less ministers and local councillors, saw no need to brandish it so clumsily any every opportunity. Apart from the far right’s efforts to steal it, and some occasional overuse by Tory eccentrics, the union flag was apolitical: Not it would seem, for very much longer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments