What are the chances of a general strike?

Such talk of confrontation adds to the general sense of tension rising as energy bills and general inflation are making it difficult, if not impossible, for families to make ends meet, writes Sean O’Grady

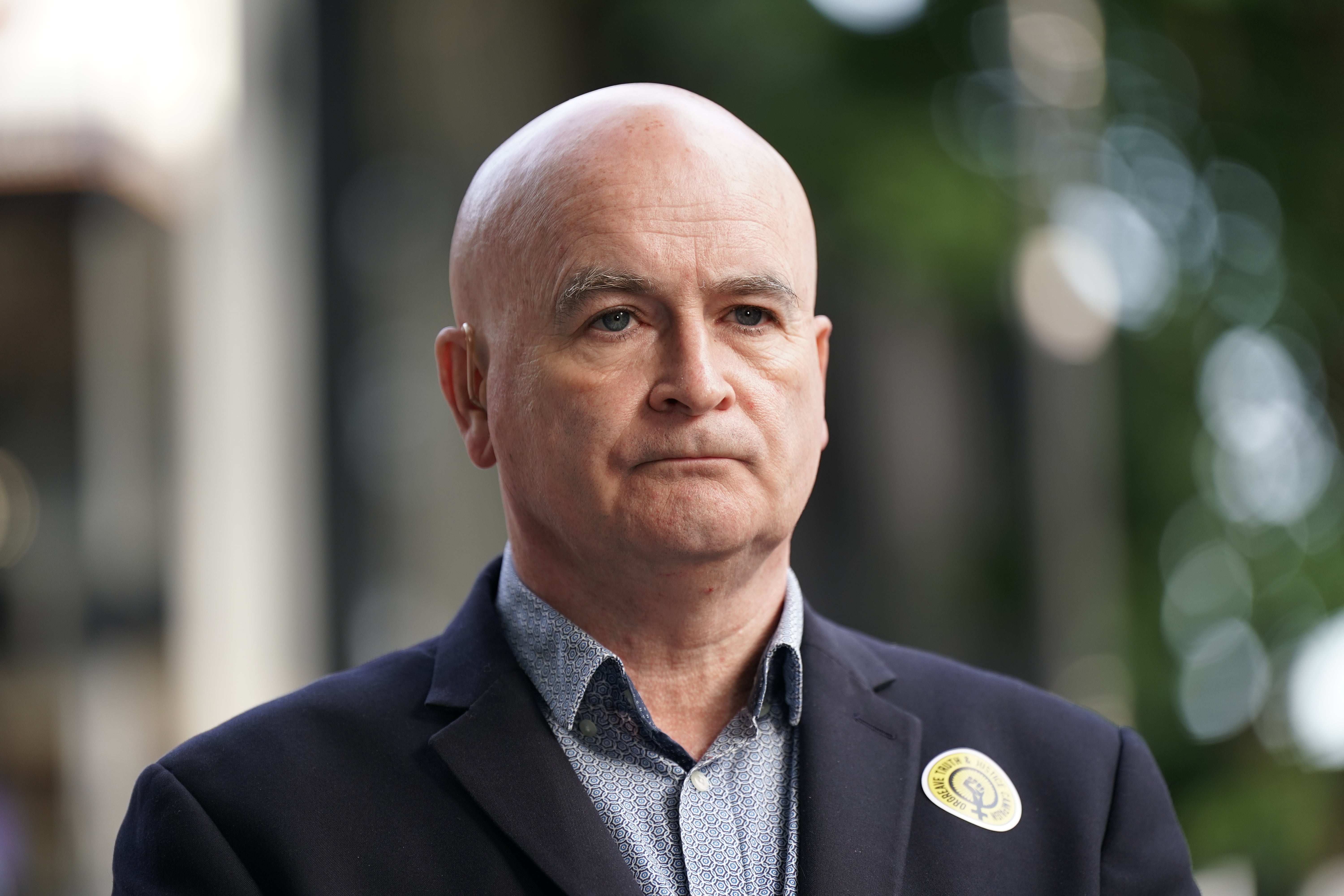

Mick Lynch, leader of the RMT union, is threatening the almost unprecedented action of a general strike because Liz Truss, and to a lesser extent Rishi Sunak, are threatening to make it virtually impossible to take effective industrial action.

That means enacting a 2019 Conservative manifesto pledge: “We will require that a minimum service operates during transport strikes. Rail workers deserve a fair deal, but it is not fair to let the trade unions undermine the livelihoods of others.”

Sometimes this is taken to mean a new law would place similar obligations on NHS workers and others in key positions, but the manifesto mandate is restricted to the railways. Truss also wants to make strike ballots more difficult to win, requiring much higher levels of democratic support among members, and less freedom over the timing of strikes.

Such talk of confrontation comes after many decades of industrial peace and almost a century since the last formal general strike, which ended in failure in 1926. It adds to the general sense of tension rising as energy bills and general inflation are making it difficult if not impossible for families to make ends meet. There is a cost of living crisis, it will intensify for many months ahead and the government seems to have no answer to it, aside from preventing workers trying to win pay increases through lawful industrial action. To take that way, as Lynch and his allies see it, is to put further stress on people and violate the fundamental right to withdraw one’s labour. Hence the threat that other unions in other sectors would pick fights with employers about pay and conditions (not difficult with inflation so high), and add to the pressure on government to leave the unions alone.

In return, Grant Shapps, the transport secretary, is talking about banning such “collusive” strikes, given that formal “secondary” action was outlawed in the 1980s. Things are escalating.

Even in the 1970s and 1980s, when trade union power, militancy and membership were all at a peak, there was talk about such widespread industrial action, but it never quite came to pass. In 1984-85, the long and bitter coal miners’ strike might well have had a different outcome if their traditional allies on the railways and other workers had come out in “secondary” action – but they didn’t. Nor did they do so in the more successful coal disputes in 1972 and 1974, though other workers did refuse to cross picket lines and offered gestures of support and solidarity, as did the Labour Party in opposition.

The nearest parallel, and a suggestive one, was the widespread wave of strikes through the public and private sectors in the “winter of discontent” in 1978-79, when at various times everyone from lorry drivers and car workers to bakers, gravediggers and the firefighters at airports walked out, in protest at the Labour government’s attempts to limit pay rises. It certainly helped destroy the government’s credibility; but the public seemed to conclude that there should be more limits on union power.

But would a general strike work in any sense this time? It could, if enough people were prepared to break the law and support protests and civil disobedience, as well as leave themselves open to the potential of dismissal over unlawful strike action. It would mean millions refusing to pay gas and electricity bills, whether they could afford to or not, and not working. The non-payment protests against the poll tax in 1990, plus widespread demonstrations by the usually apolitical, certainly helped force an eventual change in government policy and the fall of Margaret Thatcher. It was not a general strike, but a far wider popular movement.

The 1926 strike was a heroic failure. It lasted for nine days, with millions of workers, from bus drivers to newspaper printers, coming out to support the coal miners. However, the government drafted in the army and plenty of people came forward as volunteers to replace union labour. The miners remained on strike, under incredible hardship, for another six months, before they too were defeated.

The government of the day, as was to happen many times after, painted it as a conflict between parliamentary democracy and the rule of law against Bolshevik militants. It’s maybe not the kind of scrap even Liz Truss wants to get into.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments