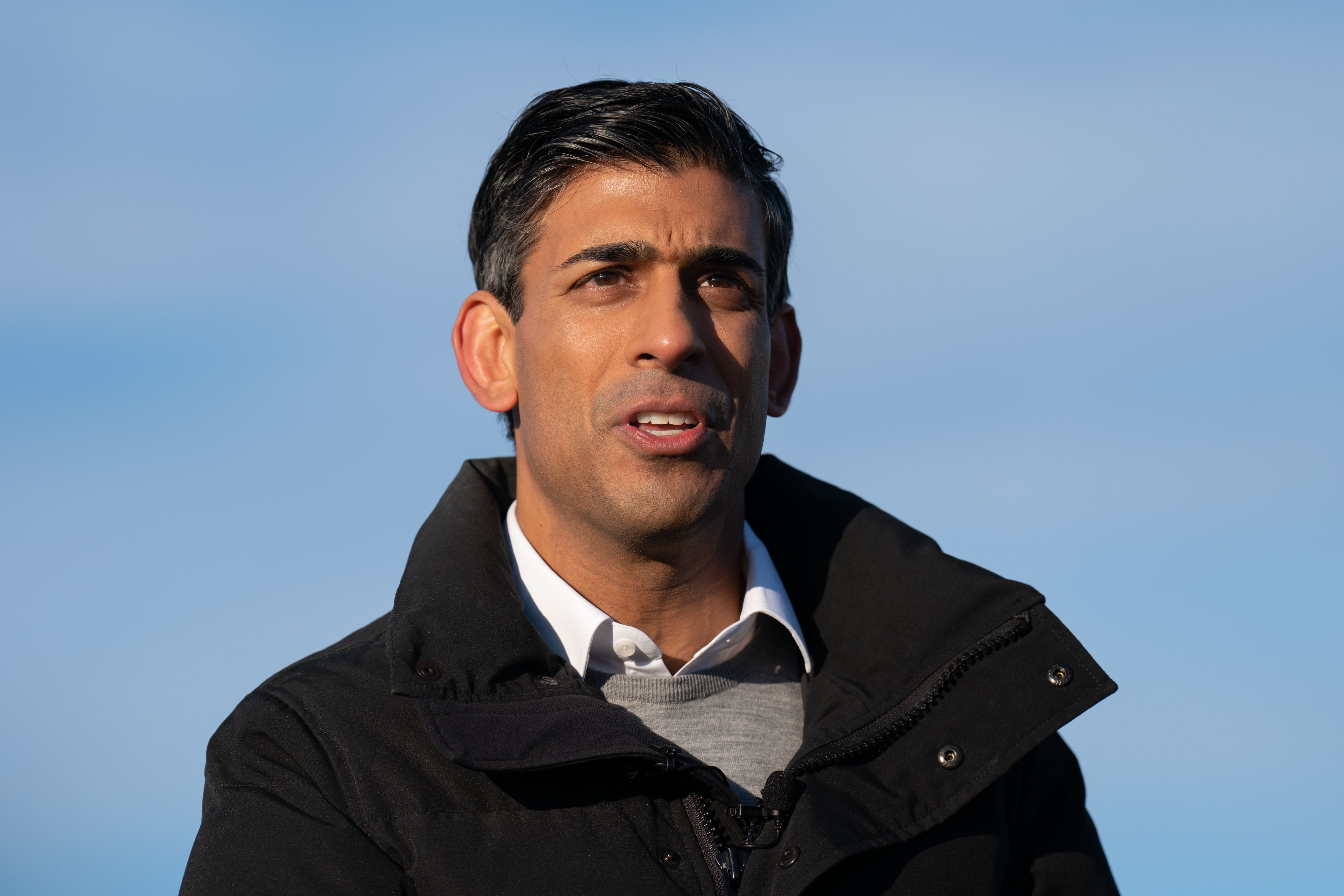

Stagflation is here and the Sunak government looks adrift

ONS data shows Britain in the grip of non-existent growth and record inflation, says Sean O’Grady

The term “stagflation” still has an odd, almost theoretical air to it. Everyone’s talking about the cost of living crisis, the labour shortage, strikes, the energy crisis, inflation, higher interest rates, food banks and incipient recession. And the consequent unpopularity of the government. Yet these apparently disparate phenomena are really all just different aspects of that handy portmanteau word: stagflation. It is upon us already.

That the UK is gripped by a lethal combination of non-existent growth and historically high inflation is more than confirmed in the latest growth numbers from the Office for National Statistics. The economy shrank by a worse-than-expected 0.3 per cent in the third quarter of the year – an annualised decline of 1.2 per cent against a “normal” contemporary growth figure nearer to 2.0 per cent, and historical averages between 2.0 per cent and 3.0 per cent.

It doesn’t sound much, but just consider that every 1.0 per cent of annual growth amounts to about £25bn of goods and services for consumption or investment. So to be that far down from trend is a sort of hypothetical permanent loss of going on for £100bn of national income. It is why politicians keep talking about growth, and we should all be concerned about the seemingly intractable problem of low growth in productivity, which has been exacerbated by Brexit.

Normally, an economy in the doldrums at least has low inflation, but stagflation means that negative growth coexists with high inflation – 10.7 per cent a year on the latest reading. This was slightly lower than expected, which might just mean that inflation has peaked and interest rates and mortgage bills won’t need to rise as quickly. But that’s a thin silver lining.

Labour shortages and the war in Ukraine have pushed the cost of producing things in Britain sharply higher, which means that there’s less money to go round. In such circumstances, different interests – public spending versus private consumption, trade unions and businesses – will be scrapping for their slice of the economic pie. Because the pie is shrinking, the struggle to protect profits, rents and wages takes a more vicious turn. Hence the strikes, and the pressure on public services and private living standards.

It hardly needs adding that stagflation is a problem for whichever party is unlucky enough to preside over it. To get inflation caused by cost-push pressures under control, and prevent a wage-price spiral, the economy really has to be hammered with tax hikes, public spending cuts and sharp rises in interest rates. Inevitably, that costs votes for the governing party. When stagflation was last a feature of life in the 1970s and 80s, it also led to political instability, civil strife, and a feeling that the country was becoming ungovernable.

A government that can develop a narrative about why its policies are necessary, and convince voters it is making progress, won’t be punished as hard as one that appears to be being helplessly carried along by events. At the moment, the Sunak administration looks very much out of control, with little time to turn things round.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments