Why the government’s back-to-school plan could bring more political peril for Boris Johnson

After a summer of abortive announcements and policy U-turns, the ability to get pupils back in classrooms – and keep them there – is a crucial test of the government’s competence, writes Andrew Woodcock

If the majority of English and Welsh classrooms are filled by children returning over the next few days, Boris Johnson and Gavin Williamson will be breathing a deep sigh of relief.

After the farcical collapse of their last attempt to get pupils back to school in June, simply reopening classrooms and persuading parents they are safe places to send their children has become a significant test of the government’s basic competence.

The hope is that getting lessons going smoothly will not only allow youngsters to resume their education but will also trigger a flood of parents back to offices and factories after months having to work from home while keeping half an eye on the children. This, in turn, could restore the urban economy of sandwich shops and restaurants and make public transport viable again.

But even if the bulk of children answer the call to come back to class – as surveys suggest they will – the challenges are far from over for the prime minister and his embattled education secretary.

The experience in Scotland, where schools reopened a fortnight ago, suggests it will not be long before millions of pupils mingling in classrooms and corridors begin to generate fresh outbreaks of the coronavirus.

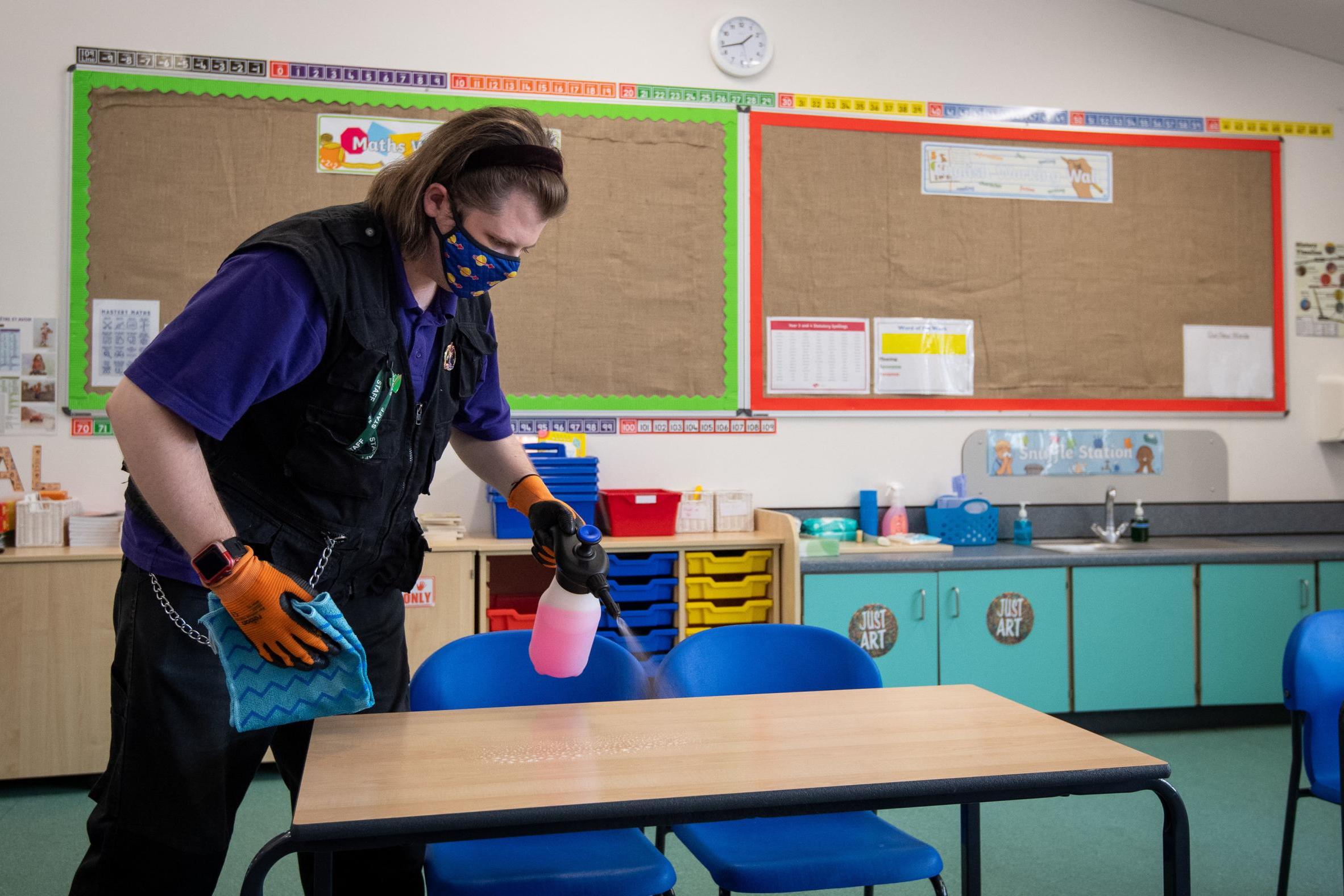

Schools are splitting students into year-group “bubbles” and staggering arrivals and lunchtimes to reduce the risk of infections.

But a survey of almost 6,000 teachers for the Times Education Supplement found that nearly nine in 10 (86 per cent) do not think it will be possible to maintain social distancing from pupils and other staff, while two-thirds (66 per cent) fear guidance to avoid busy corridors, entrances and exits is unrealistic.

Guidance is in place for any child showing symptoms of Covid-19 to be sent home for testing, with classmates – and potentially entire year groups – likely to be asked to self-isolate if the outcome is positive.

Ministers insist that closing schools is an absolute last resort in any wider flare-up in communities, with school leaders told to try teaching by rota, with different groups of pupils coming in at different times, in order to keep doors open.

But any disruption to classes will quickly have knock-on effects, by preventing parents from getting on with working life. And it will increase concerns about year 11 and 13 preparations for crucial GCSEs and A-levels in summer 2021.

Already, Labour is calling for the tests to be delayed by one or two months to give pupils more time to prepare. Pressure for a delay – or even cancellation – of exams will grow the more days are lost to self-isolation.

A survey by the National Association of Head Teachers shows that more than 700 English schools, or 3 per cent of the total, are already planning to avoid full reopening this week, instead phasing students back in a “transition period”.

Failure to keep lessons running on a normal day-to-day basis would undermine, possibly fatally, Mr Johnson’s efforts to encourage the return to normality which is now essential to shore up the UK economy.

After a summer of abortive announcements and policy U-turns, the prime minister is badly in need of a government initiative which goes to plan, in order to counter the growing impression that his is an administration characterised by incompetence, flying by the seat of its pants rather than forecasting potential problems and making effective preparations to deal with them.

For Mr Williamson, his ears ringing with demands for his dismissal after the exam grading fiasco, any widespread disruption to the autumn term may prove the final straw that breaks his cabinet career.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments