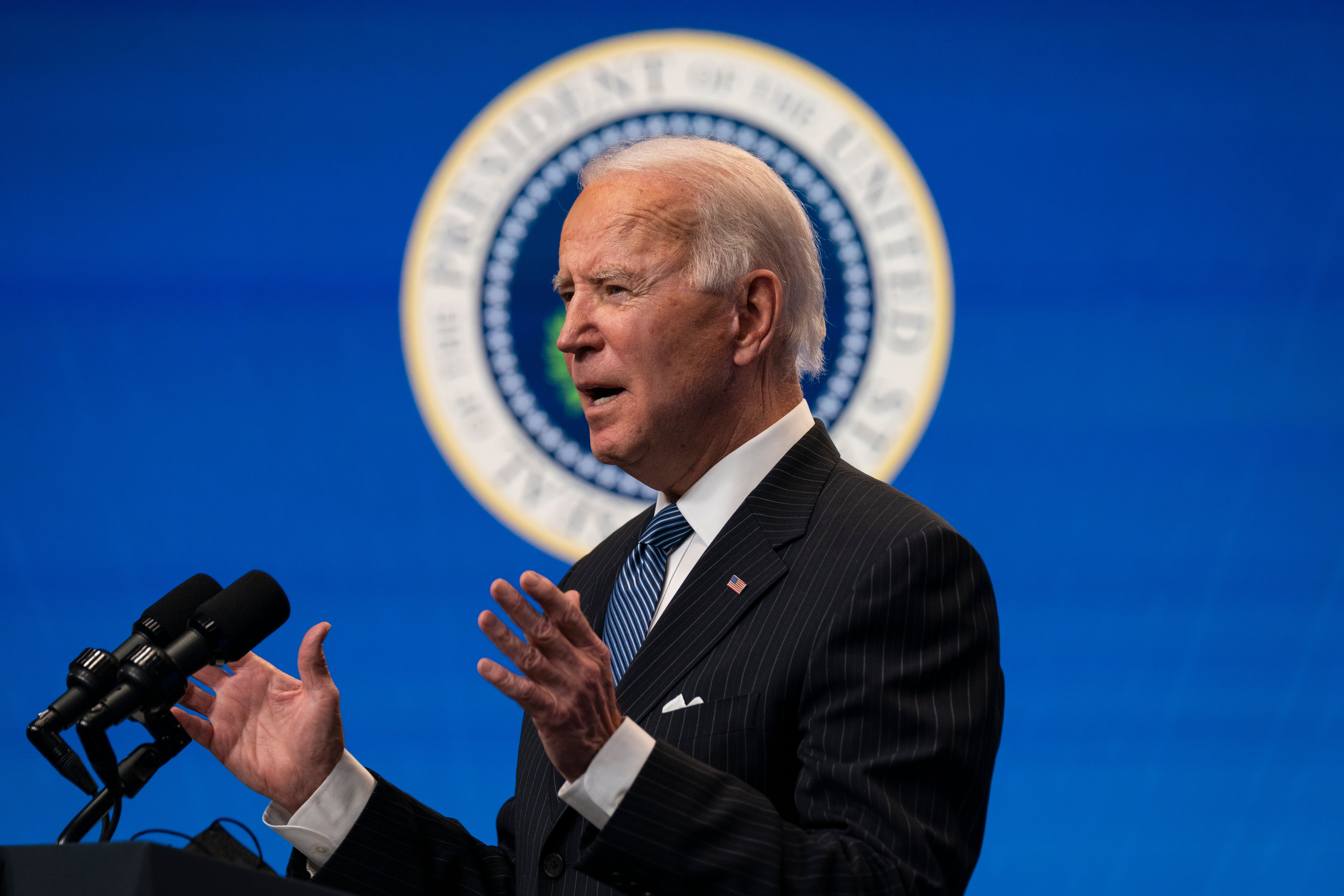

How will US relations with Russia change under President Biden?

Sean O’Grady considers what the future holds for ties between the White House and the Kremlin after Trump’s departure

President Putin must be missing Donald Trump already. In the long-established diplomatic code used in such communiques, the White House “read out” reports that Joe Biden “raised matters of concern” during his phone call to Vladimir Putin, their first conversation since Mr Biden took office. President Biden “made clear that the United States will act firmly in defence of its national interests in response to actions by Russia that harm us or our allies”.

Clear enough, when decoded, and foreful stuff – a marked departure from the usually soft approach of the Trump administration. The Kremlin, for its part, was a little less opaque: “On the whole, the conversation between the leaders of Russia and the United States was of a businesslike and frank nature. It was agreed to maintain contacts.”

The “hot line” remains open, then, but there is no mistaking that relations between the two countries are being placed in a more normal footing. As every president before Donald Trump has done, Mr Biden was firm in his objections to Russia’s recent international behaviour, and the list of transgressions is a lengthy one. President Biden raised hacking of US government computers, the Russian bounties in US troops in Afghanistan, interference in US elections, the attempted assassination of Alexei Navalny, and the sovereignty of Ukraine.

Neither man is much given to the kind of histrionics President Trump was sometimes prone to, but each leader will have been left in no doubt about the other’s attitude. On the positive side, neither man allowed these arguments to wreck renewal of the New Start arms control agreement. Whatever else, it is in the national interest of America, and of Russia and indeed in the whole world, to restrict the nuclear arsenals of these military superpowers. President Putin, worryingly, is committed to ramping up Russian military spending, which his country can ill afford.

On many areas it was always curious that President Trump failed to make any real protest about Russian policy, most bewilderingly after reports that Moscow had funded bounty rewards for the dead bodies of American and allied soldiers in Afghanistan. Mr Trump also publicly repudiated his own intelligence agencies when he appeared with Mr Putin at the Helsinki summit in 2018.

It was then that President Trump placed the assurances of President Putin ahead of the work of the law enforcement agencies. It appalled many, and made some wonder if the Russians possessed kompromat on Mr Trump. Support for Britain over the Salisbury poisonings and the US bombing of Russian proxies in Syria were rare examples of the Trump administration standing up to Russia.

So the reset button has been pressed and, as in so many other fields, the policies of the Obama administration reinstated. With those, though, come the same difficulties and dilemmas. The extension of the Start treaty shows the benefit of cooperation, but the Russians seem unresponsive to either pressure or reason.

Mr Putin seems an old-fashioned nationalist autocrat who equates national prestige with territorial expansion and aggression, and in the modern age that includes mostly low-level cyber warfare, the descendent of Russia’s long and successful tradition of spying. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union itself, the ideological battle and the Cold War seemed over – the “end of history” as it was called. Now a primitive form of Russian nationalism of an older stripe has taken its place, and now joined and complicated by a more assertive China.

In other words, President Biden is left with the same kind of questions faced by most of his predecessors from Harry S Truman onwards. When should America threaten to use force? How far should the West trust the Russians? How can China be drawn into partnership as a counterweight to Russia, or, as Mr Trump saw things, vice versa? Is detente consistent with human rights? How will America wind down its proxy wars with Russia played out with great cruelty through the likes of Israel, Saudi Arabia, Iran and various terrorist groups in Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and elsewhere?

Many of the arguments of today about the futures of Taiwan, North Korea and the Middle East would have been familiar to Eisenhower, Stalin and Mao. President Biden may lean towards a thawing of relations, as has happened before, with treaties and summits, as under Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter and the end of the Reagan presidency and that of George HW Bush; but the record suggests that such relatively hopeful episodes are also relatively short-lived. We may expect many more chilly calls between Mr Biden and Mr Putin.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments