What does the Aukus nuclear submarine deal mean for world politics?

In both the short and long term, the principal risk is that China and Russia will be pushed closer together by the pact, writes Sean O’Grady

The US, UK and Australia have unveiled details of their plan to create a new fleet of nuclear-powered submarines, aimed at countering China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific region.

Under the Aukus pact, Australia is to get its first nuclear-powered subs – at least three – from the US, much to the chagrin of Beijing.

What is Aukus and the nuclear submarine deal?

There are at least three answers to that. First, at its centre is an agreement between Australia, the UK and the US (hence the acronym) whereby Australia can get some nice new nuclear-powered submarines, with the help of its allies providing classified information and know-how.

The subs will not carry nuclear warheads like their British and American counterparts, but they will be powered by miniature nuclear reactors rather than diesel engines. This means they have a far wider range and can spend longer at sea than they would if fitted with internal combustion engines; and they are also quieter and harder to detect. Thus, the Royal Australian Navy will have a transformative new weapon at its disposal.

Behind that, the allies are also committed to even closer cooperation on intelligence sharing, cyberwarfare and other advanced potential “battlegrounds”. The three are already in the Five Eyes intelligence network (with Canada and New Zealand), the US and UK are leading members of Nato, and Australia has an existing defence pact with America.

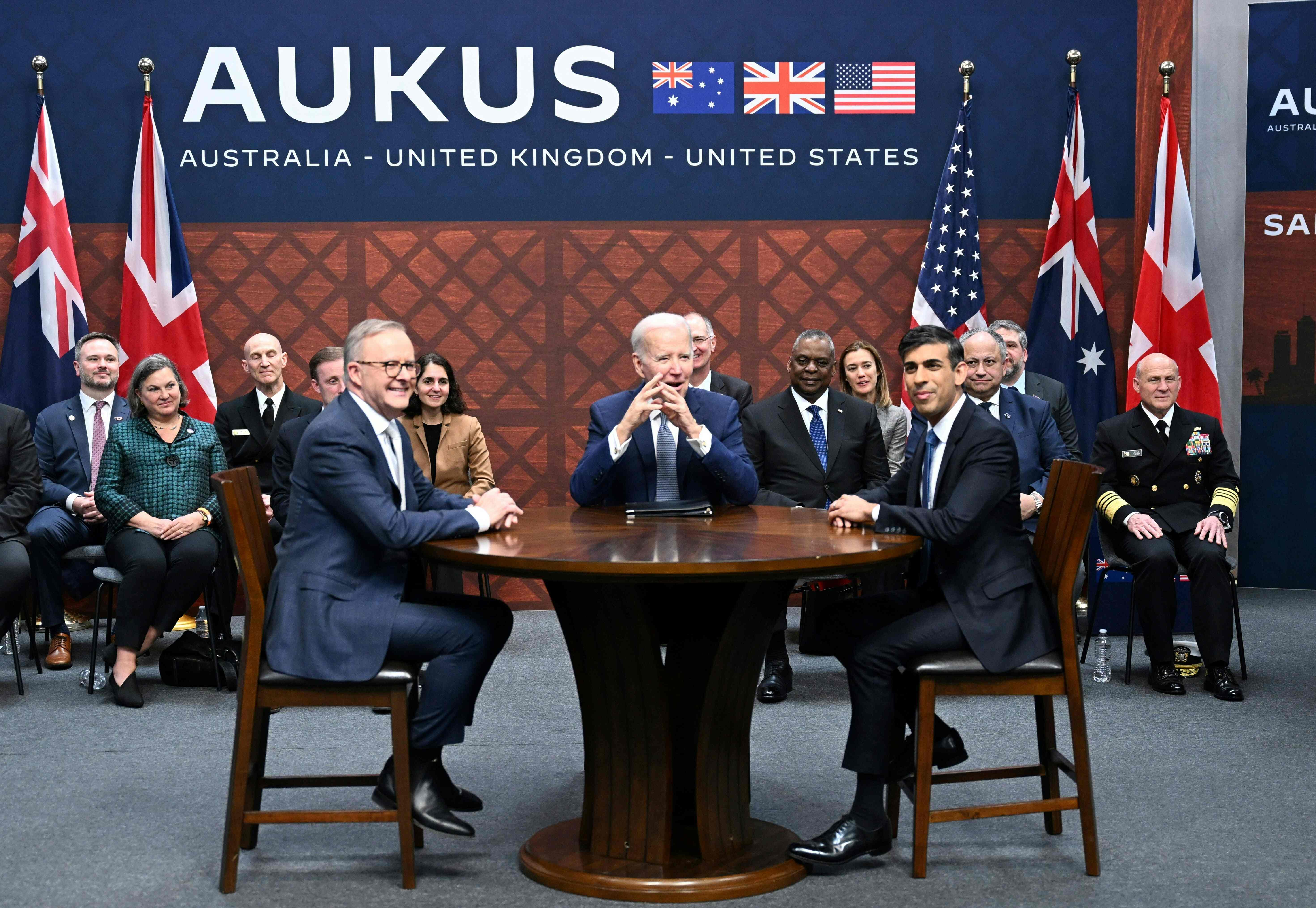

Thus the three are also making a “statement” globally about their willingness to defend Western interests and the international order. The summit in San Diego between Joe Biden, Anthony Albanese and Rishi Sunak, was to reaffirm and add some momentum to the new alliance. They made no secret of the fact that they, and other allies in the region such as Japan, South Korea and the Philippines, are concerned about Chinese territorial expansionism and industrial power. Taiwan, a self-governing state that China still regards as part of its sovereign territory, is most obviously a bone of contention and the most exposed to actual military action.

In Sunak’s words, China “represents a challenge to the world order” – though not (yet) a threat.

What will it mean for world peace?

The Western theory is that it will stabilise the region on the time-honoured principle of deterrence. The most extreme expression of this has been President Biden’s pledge last year to assist Taiwan militarily in the event of an “unprecedented attack”, even though China has historically ruled out the use of force provided Taiwan doesn’t declare independence. (In those respects, the situation is not analogous to Russia and Ukraine). The pact is also designed to bolster that general support to the smaller powers in the region, from Japan to Vietnam to Malaysia.

To China however, it is interference by other powers in its “backyard” – especially Taiwan and the South China Sea, to which it lays disputed claim – much to the alarm of its neighbours. China says it feels it is being “encircled,” always a dangerous mindset for an ambitious power, and that the West is playing geopolitical games. Beijing says that: “The latest joint statement from the US, UK and Australia demonstrates that the three countries, for the sake of their own geopolitical interests, completely disregard the concerns of the international communities and are walking further and further down the path of error and danger.”

So what are the dangers?

Not yet war, though the escalation in tensions and the alignment of regional powers is unmistakable. On one side we find China, North Korea and Russia, plus smaller nascent client states such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands; on the other, Aukus plus Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and perhaps Vietnam. The key swing power is India, which has grown closer to Russia in recent times, and where relations with China (soured by rivalry and territorial disputes) have been thawing a little. New Zealand under Jacinda Adern had been notably less hostile to China than Australia; while France, also a regional player through overseas territories, has been angered by the way the Aukus pact cancelled a lucrative submarine contract of its own with Australia.

In both the short and longer term, the principal risk is that China and Russia will be pushed closer together because “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”, ie America. If China steps up its assistance with Russia under its pledge of friendship “without limits”, it will make the war in Ukraine much harder for Ukraine’s President Zelensky to win. An actual China-Russia pact, with junior members such as Belarus, North Korea, Venezuela, and Iran involved, would be a bizarre and lopsided one, but also quite formidable in certain respects, such as sheer scale of manpower, combined nuclear arsenal, and access to industrial resources. Although it appears very unlikely at this stage.

However, it is certainly disturbing to see how two alliances could potentially be slowly forming to menace one another, as was the case before the last two world wars and the Cold War.

Is the pact good for the UK economy?

Yes. It should mean jobs in the BAE shipyard in Barrow-in-Furness, and Rolls-Royce, based in Derby, will build the nuclear reactors, and Sheffield Forgemasters will also fabricate parts. There will be other business to be won in the supply chains. Of course, it might be better for humanity if the investment were directed at more purely peaceful projects but to proponents of the Aukus agreement, it will be money well spent on preserving world harmony.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments