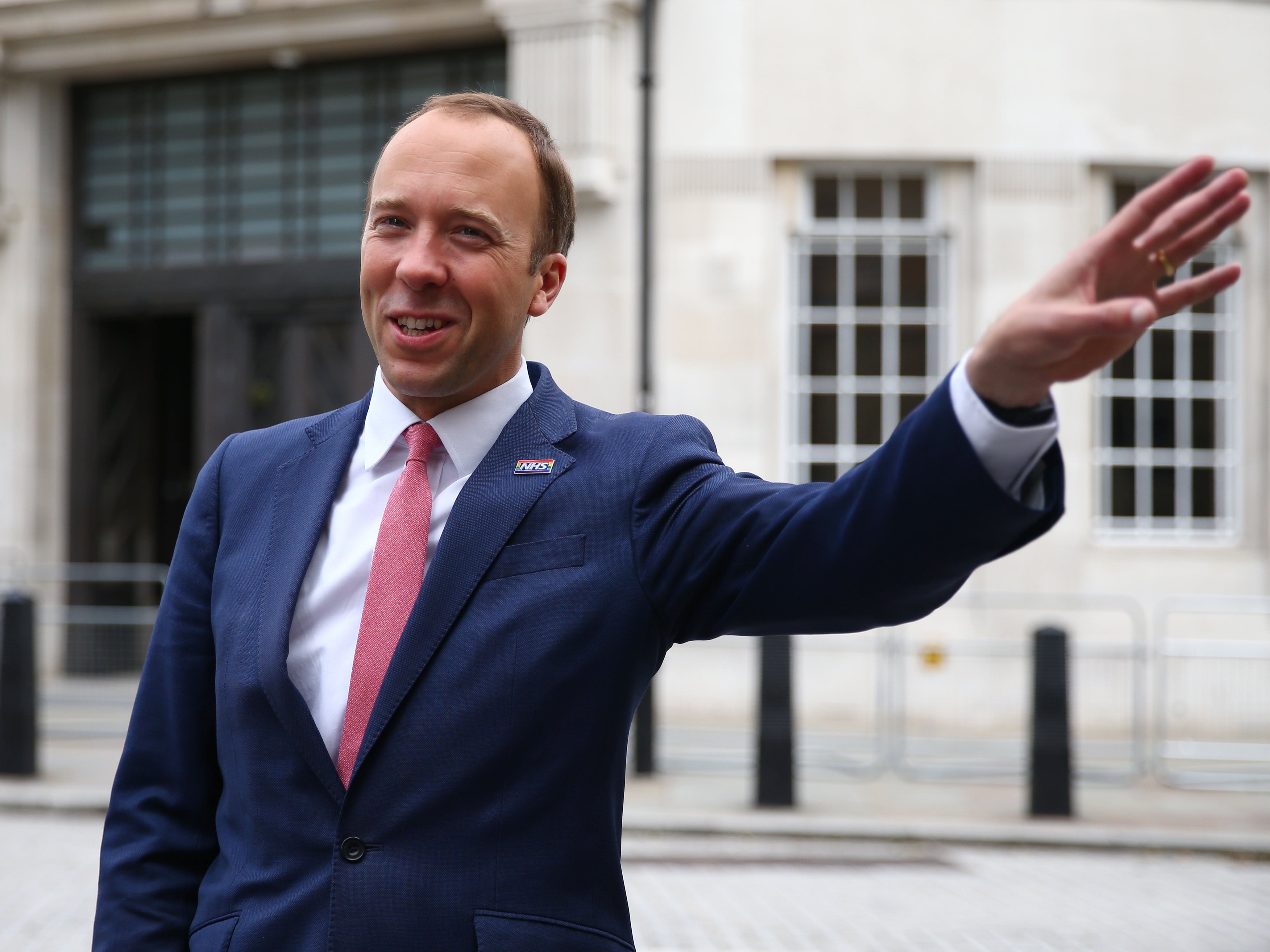

Can Matt Hancock survive being branded ‘hopeless’ by his own prime minister?

Voters appear to be willing to overlook a lot if they think Covid is being beaten, writes Andrew Woodcock

As political putdowns go, there can be few harsher than Boris Johnson’s three-word summary of his health secretary: “Totally f****** hopeless.”

Downing Street has made no attempt to deny that the WhatsApp message published on Dominic Cummings’s blog is genuine, and Matt Hancock has restricted himself to replying “I don’t think so” when asked if the description was accurate.

But No 10 equally said that the prime minister had “full confidence” in his health secretary and indicated he will be keeping his job, for the time being at least.

Cummings has previously said that Johnson was being encouraged to keep Hancock in the cabinet so as to have someone to sack if things went badly wrong in the coronavirus crisis.

But many voters will be asking themselves why he was not sacked long ago, if the prime minister rated him so low at precisely the point when his role was so important in terms of delivering PPE, tests and vaccines, protecting care homes and keeping the NHS operational.

To some extent, the ferocious attack on the health secretary by Johnson’s former adviser at last month’s House of Commons committee hearing made Hancock less sackable, as the prime minister couldn’t be seen to be taking orders from Cummings, who was anyway rated lower for credibility by voters than virtually anyone else in public life.

But when the damning criticism is in Johnson’s own words – tapped out in the middle of the night on his mobile phone as he awaited his Covid test result in the darkest days of the first wave – that argument carries much less weight.

It is well known that Johnson doesn’t like sacking people who are loyal to him. While he happily threw long-serving Conservative stalwarts like Kenneth Clarke out of the party for objecting to a no-deal Brexit, he hung onto Priti Patel after she was found to have bullied staff, Gavin Williamson when the school exam system collapsed and Cummings himself when he undermined lockdown with his trip to Barnard Castle.

And so far, the opinion polls suggest he has not suffered for it in popularity terms, with ever-extending leads over Keir Starmer despite the soaring Covid death toll and increasing evidence of the harm done by Brexit.

A lot of that is down to the “vaccine bounce”, with voters concentrating more on their gratitude for being offered an escape route from the pandemic than their concerns about the way it has been handled.

But there is also the issue that voters seem to have factored in a certain degree of chaos and incompetence in the Johnson administration.

If the prime minister can survive calling black people “picaninnies with watermelon smiles”, how much harm can it do if he calls his health secretary “hopeless”? If he can sign an international treaty that bars the movement of sausages from one part of the country to another, will voters be all that surprised that he kept someone in a job that he didn’t think he could do?

Voters have shown they can keep on giving Johnson their support even while regarding him as a liar – as polls suggest they do over issues such as the government’s initial support for “herd immunity” and his reported comment that he would rather see “bodies pile high” than order a third lockdown.

They will be aware that many who have had dealings with the prime minister report that he appears to say whatever he believes the person he is talking to wants to hear.

When talking to a foul-mouthed adviser who hates Matt Hancock, why wouldn’t he think that branding the health secretary “f****** hopeless” was the best way to reply? It certainly makes you wonder what he said about Cummings to Hancock in any late-night texts they may have swapped.

At the root of the apparent imperviousness of Johnson and Hancock to criticisms of this kind is a general public view that no one else was likely to have done any better in the circumstances.

There are clear signs that voters are giving the government a lot of leeway in dealing with what they see as a nightmare situation with no rulebook available and no clear answers on what to do.

Cummings himself is clearly in no doubt that different personnel willing to challenge received ideas and act more swiftly and more radically could have significantly reduced the impact of coronavirus on the UK, both in lives lost and economic damage inflicted.

But his arguments will struggle to gain purchase so long as voters’ attention is fixed on the promised return to normality. It might take a significant shock – a new variant that is resistant to vaccines, a further delay beyond 19 July in the removal of restrictions, or the reversal of relaxations permitted in recent months – before the collective mind of the public turns to the question of who is to blame for all they have suffered.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments