Why is the wording of Labour’s Clause IV such a conference issue?

Whatever Clause IV might eventually say, the Labour Party is being upended and the baggage of public ownership loaded back on board, writes Sean O’Grady

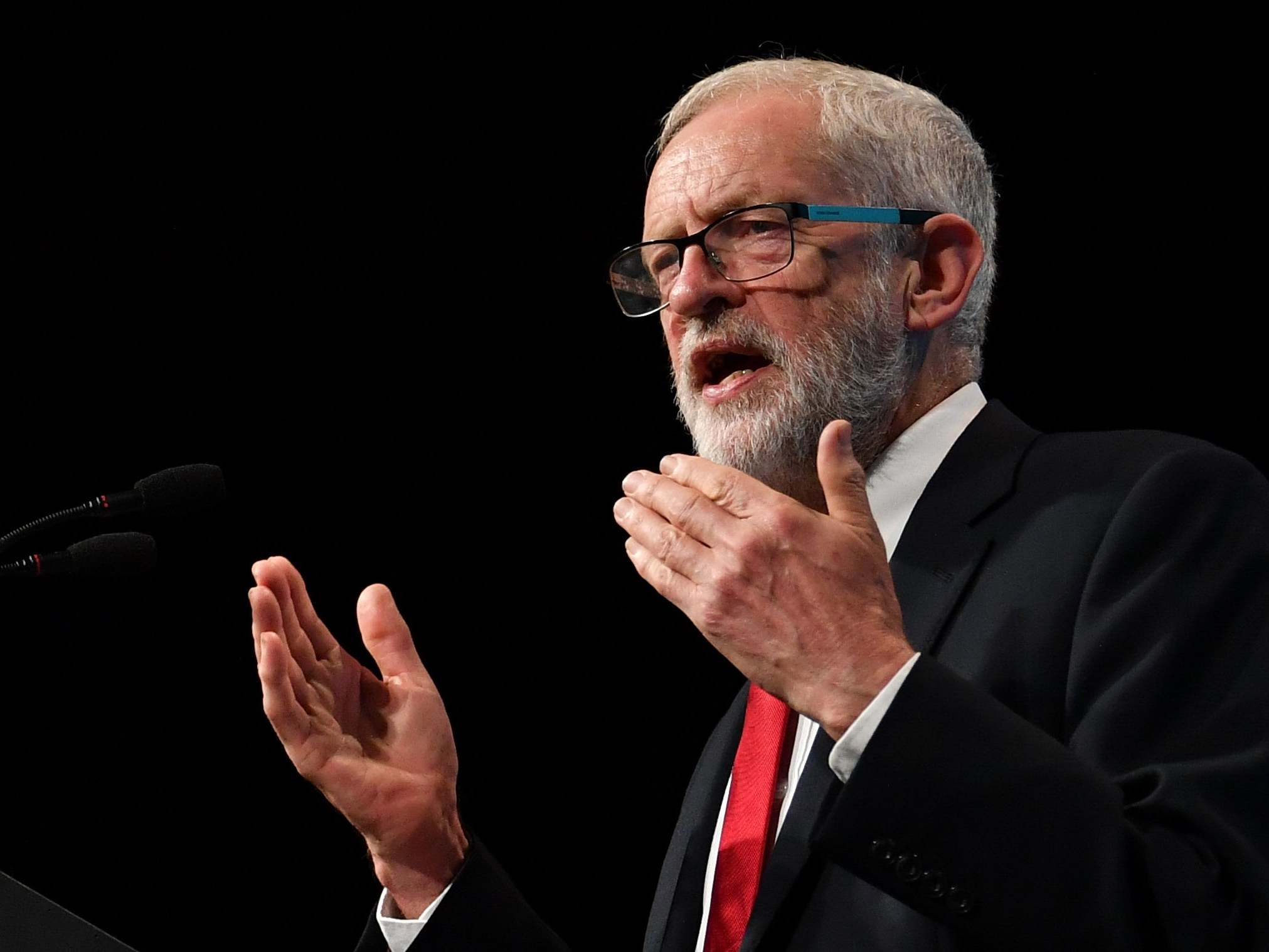

When Jeremy Corbyn became leader of the Labour Party in 2015, many of its members, old and new, felt as though they had “got their party back” – not least the ancient belief in public ownership, once enshrined in Clause IV of the party’s constitution, the party’s original “mission statement”, as it might be termed nowadays.

In substance, so it has proved, in the sense that much of the old Blairite, social democratic, centrist settlement – itself an accommodation with market capitalism and Thatcherism – has been denounced, its totems trashed, and “socialism” is once again the language and policy of the wider Labour movement. Four years ago, Corbyn cheerfully volunteered: “I think we should talk about what the objectives of the party are, whether that’s restoring the Clause IV as it was originally written or it’s a different one, but I think we shouldn’t shy away from public participation, public investment in industry and public control of the railways.”

However, there has until now been little real pressure to reinstate the party’s historic constitutional commitment to “common ownership”, or nationalisation, muscular as the policies of John McDonnell and Rebecca Long-Bailey may be. It is that constitutional formality that some constituency Labour parties are now hankering after and agitating about. They argue the original, poetic text of Clause IV, dating back to 1918 – with all the transformative ambition attached to it – should be restored, like an Edwardian frieze that had been ripped from the facade of a beloved temple by some “modernising” philistines.

In reality, although Corbyn and the leadership remain sympathetic to a stronger expression of socialist values, for romantic reasons at least, they are disinclined to go back to the antique phrasing of the text adopted more than a century ago, and the wrangling that would go with that. They will instead ask the Webbs’ heirs in various nostalgic CLPs to “remit” their motions. The ever-thorny theological discussion about Clause IV will instead be referred to a working group – “kicked into the long grass”, to use the common parlance.

Even for Corbyn, trying to restore or redraft Clause IV is a step too far, for now. It is such an exercise in navel-gazing that even he cannot indulge in it, as a difficult general election fast approaches. In practical terms, Labour is already committed to a vast extension of public ownership in larger quoted companies – up to 10 per cent in due course – and to taking the railways and other public bodies back into state ownership and/or control. The ideology behind the policies is purely decorative.

In a way, on aesthetic grounds, it is a pity. Even Labour’s most entrenched enemies admit the charm of the old form of words, crafted by Sidney and Beatrice Webb, pioneering Fabian socialists, shortly after the Russian revolution: “To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.” Like the “Red Flag”, true believers could recite the words.

The aim of socialist society built on “common ownership”, albeit a distant, almost millenarian one, dates back to before the first Labour government had even been formed, and came nowhere near enactment until the Attlee government embarked on a substantial programme of public ownership after 1945 (railways, coal, road freight, the Bank of England, electricity and gas supply, and even an attempt on the sugar industry). More followed in the 1960s (steel, buses) and the 1970s (British Leyland, shipbuilding, aerospace, parts of North Sea oil).

Yet it was not too long before nationalisation of industries (as opposed to the National Health Service, say) became an often loss-making laughing stock, a byword for inefficiency and union power, delivering intermittently poor services at inflated cost – as compared with the emerging power of private enterprise and its ability to deliver the new marvels of the consumer age to a public eager to expand its horizons and raise its living standards. “Nationalisation”, “common ownership”, “public ownership”, whatever became an embarrassment, synonymous with failure and national decline, a stick with which to beat Labour, and reference to Clause IV was always resorted to when Conservatives ran out of rational arguments.

An attempt after the disastrous 1959 election by a “revisionist” social democrat Labour leader, Hugh Gaitskell, to replace Clause IV completely failed. Indeed, “trying to take the Book of Genesis out of the Bible”, as it was derided, was so counterproductive that the old Clause IV was then printed on every Labour membership card. As a matter of historic curiosity, Gaitskell’s wording was not as radical as what was to come in the 1990s, and in fact provided for further nationalisation of the “commanding heights” of the economy. Corner shops and farms were safe, however: “Further extension of common ownership should be decided ... with due regard for the views of the workers and consumers concerned.” It was rejected, and the party decided to “reaffirm, amplify and clarify” Clause IV with the unexceptionable declaration that the Labour Party’s “central ideal is the brotherhood of man. Its purpose is to make this ideal a reality everywhere.” (That latter phrase was a reference to decolonisation, though entirely unnecessary.)

Tony Blair made a much more determined assault on the old Clause IV, and his, unlike Gaitskell’s, was better planned. Blair also had the great advantage that, by 1995, privatisation rather than nationalisation was the accepted norm, and almost everything in the public sector had been sold off. Only the royal mail and the BBC were left in the cupboard.

Labour had by then entirely accepted the power of the dynamic market economy to create wealth, and of private enterprise to provide the finds to support employment, living standards and thriving public services. Blair’s new Clause IV was very much of its time, and quite verbose. Clause IV now reads (in part): “The Labour Party is a democratic socialist party. It believes that by the strength of our common endeavour, we achieve more than we achieve alone so as to create for each of us the means to realise our true potential and for all of us a community in which power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many not the few, where the rights we enjoy reflect the duties we owe, and where we live together, freely, in a spirit of solidarity, tolerance and respect.

“To these ends we work for: a dynamic economy, serving the public interest, in which the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition are joined with the forces of partnership and cooperation to produce the wealth the nation needs and the opportunity for all to work and prosper, with a thriving public sector and high-quality services, where those undertakings essential to the common good are either owned by the public or accountable to them.”

Utterly unmemorable, which was perhaps just the point. It was Blair’s “Clause IV moment”, more symbolic than operational, an outward signal that Labour had changed, and become New Labour, its ideological baggage dumped. The creation of wealth was now more important than its subsequent distribution. Now, whatever Clause IV might eventually say, the party is being upended again, and the baggage of public ownership loaded back on board.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments