Esther McVey and the chequered history of the Tory ‘dream ticket’

Jeremy Hunt and the former breakfast TV host are not the first Tory odd couple as Sean O’Grady explains

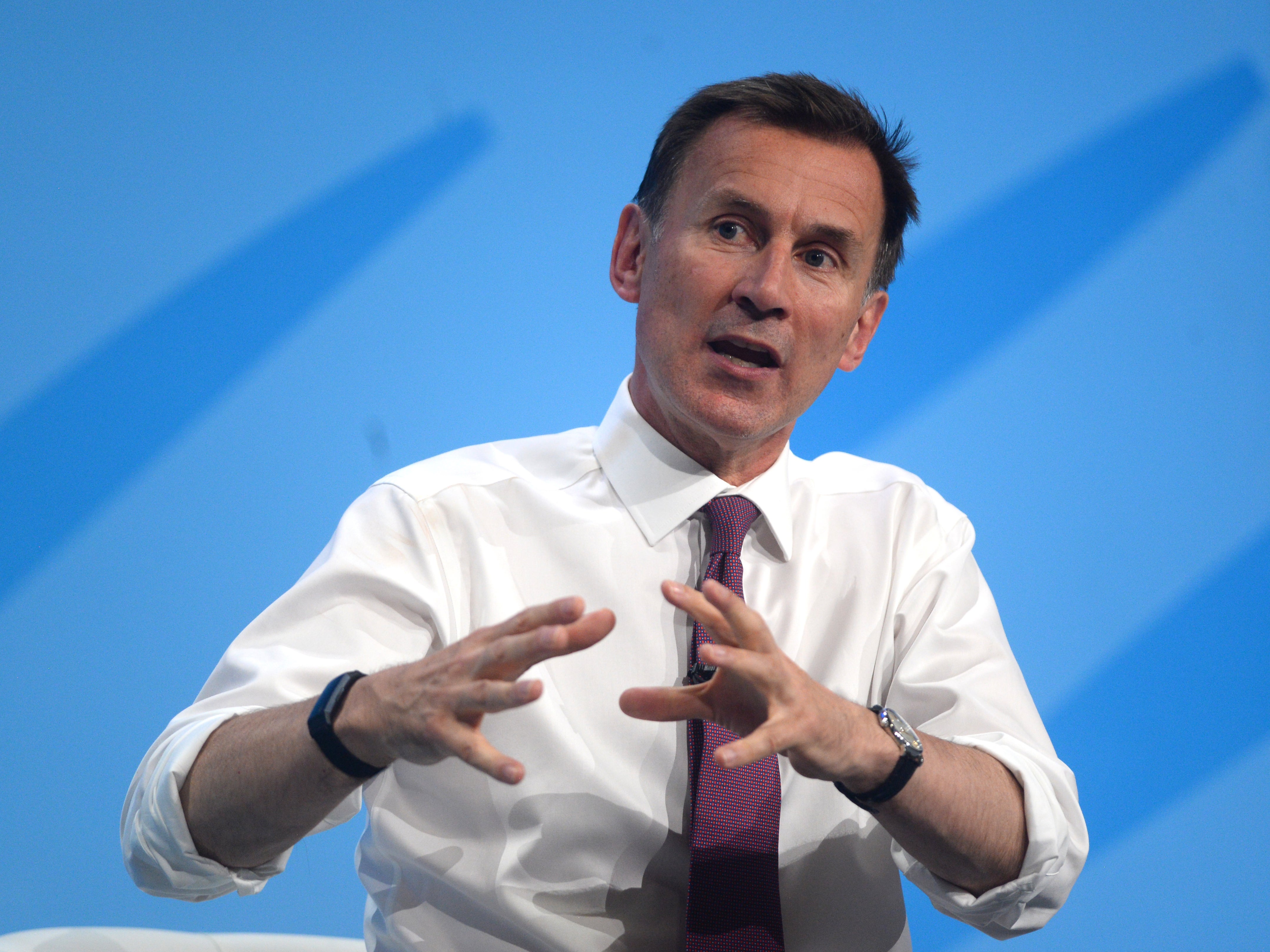

Jeremy Hunt’s nomination of Esther McVey as his deputy-leader designate – and therefore also deputy-prime minister designate – is certainly something of a surprise. He is often lazily thought of as a kind of moderate in Tory terms, having expressed some caution about radical tax cuts and previously having backed Remain in the EU referendum and ruled out a no-deal Brexit in the traumas of 2016 to 2019. He remained aloof from the Johnson cabinet.

McVey, on the other hand, is critical of Johnson for not being aggressive enough on the EU, or on tax cuts or on refugees. Of course, there has been some convergence in their stances lately, with Hunt advocating a widening of the Rwanda scheme to other host nations, but there’s no denying that Hunt and McVey are an odd couple.

What’s in it for them? You’d suspect that Hunt is desperate to widen his appeal and dissolve the assumption he’s some sort of liberal “Remoaner”, hence tacking hard to the right and recruiting someone with red-wall appeal to balance his southern background. It may be she was the only person on that wing willing to join Team Hunt, given that he’s been the antithesis of populism since losing the leadership race in 2019. It may also be that a fine grace-and-favour country house for Deputy Prime Minister McVey, such as Dorneywood, may also have been an attraction for her and her husband Phil Davies, MP for Shipley. A handy backbench “buy one, get one free”, then.

Tory precedents for a balanced “dream” ticket are not promising. In 1997, for example, with the Tories in shock from the Blair landslide, there was a mood for unity and change after the bitter divisions of the John Major era. So there were actually two dream tickets. The first was based on age and experience rather than major ideological differences. Michael Howard sought to add youthful energy to his candidature and recruited the then youthful and energetic William Hague as his de facto running mate and presumed next shadow chancellor. But late in the day, close friends of Hague such as Alan Duncan urged him to dump Howard and run in his own right. Hague came second in the first ballot, not far behind Ken Clarke, and Howard came bottom and dropped out.

After that, in a bid to stop Hague, Clarke and fourth-placed John Redwood formed an unlikely pact. With Clarke as leader and Redwood as shadow chancellor – intractable issues such as joining the euro would be solved with filial love. The pairing of the Europhile, One Nation Clarke and the Eurosceptic Thatcherite Redwood (who’d resigned from the Major cabinet) was ridiculed as the most bizarre and cynical alliance since the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and most of Redwood’s supporters duly defected to Hague. Tory backbenchers aren’t easy to lead.

However, the most spectacular blow-up was during the Tory leadership contest in 2016. The EU referendum that June had established Johnson and Michael Gove as a political double act and they shared much in outlook and ambition. The widespread assumption was that this pair would form an axis around which the first post-Brexit government would rotate, with Gove as chancellor doing the hard graft and putting in the intellectual effort, with Johnson the fairground barker, the front of house star of the show.

But three hours before nominations closed, Gove declared he was no longer backing his old friend – they’d known each other since Oxford days – and declared his own candidature. He knifed Johnson “in the front” and went on to disparage Johnson’s abilities, in prophetic terms. “I also believed we needed someone who would be able to build a team, lead and unite. I hoped that person would be Boris Johnson,” he told reporters. “I came in the last few days, reluctantly and firmly, to the conclusion that while Boris has great attributes he was not capable of uniting that team and leading the party and the country in the way that I would have hoped.” Wounded Johnson withdrew, to the dismay of his loyal fans, and Gove finished a poor third behind May and Andrea Leadsom. May appointed Johnson as foreign secretary and left Gove on the backbenches until she lost her majority in the disastrous 2017 election.

While the pair sort of made up in 2019, out of mutual political self-interest, some bitterness must have lingered and Gove was always given important but arduous briefs such as Brexit or levelling up, rather than the glamour and status of, say, the Treasury, Foreign Office or Home Office. The final denouement came last Thursday when Gove privately gave Johnson until 9pm to quit or he’d resign, to which Johnson responded by publicly sacking Gove at one minute to nine.

As the old saying goes, there are no friendships at the top of politics, and sometimes, in extremis, not even room for enemies to coexist without trying to destroy one another. No doubt the Hunt-McVey relationship has got off to a reasonable start, but it doesn’t feel like a marriage made in heaven.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments