What does the Greensill scandal mean for the future of lobbying?

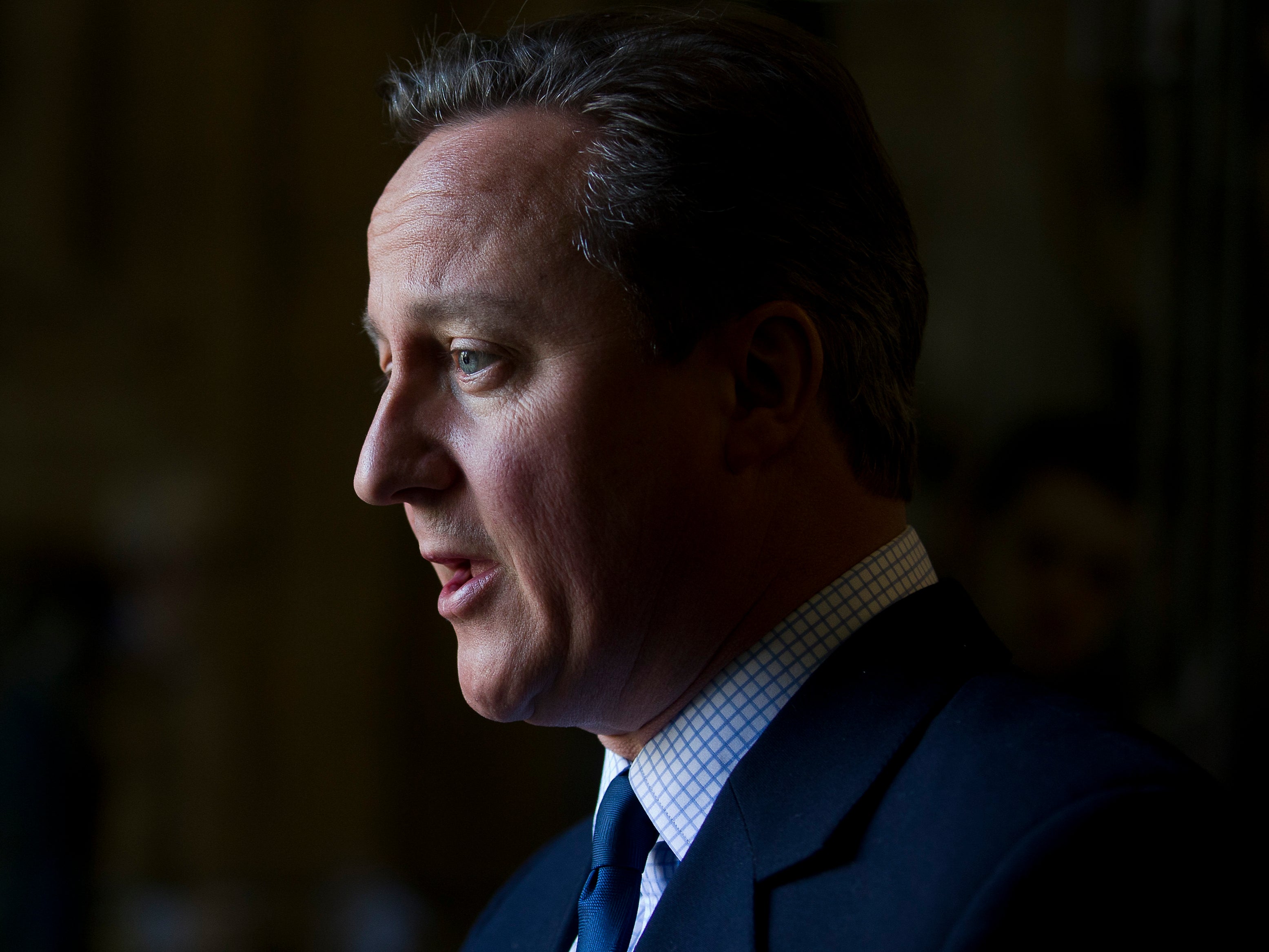

David Cameron’s antics may have removed some of the obstacles to long-awaited reform, writes Sean O’Grady

Friendless as he has been ever since the loss of the Brexit referendum, David Cameron is now the subject of a Whitehall-wide inquiry into his lobbying activities on behalf of the Australian financier Lex Greensill, and his company Greensill Capital, and associated interests. The review will be headed by Nigel Boardman, a member of the board of the Department of Business, a partner at solicitors Slaughter and May since 1982, and winner of the Lawyer of the Decade award from Financial News.

Whether he wins the award for Report of the Decade remains to be seen. Labour has already derided his appointment. Rachel Reeves, shadow cabinet office minister, offered him this frosty welcome: “This has all the hallmarks of another cover-up by the Conservatives ... This is another Conservative government attempt to push bad behaviour into the long grass.”

None the less, all government departments are being asked to go through their diaries and records to ferret out any stray texts from the former prime minister, and to track down any “informal” meetings with him. We already know about the text messages Mr Cameron sent to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, as a result of which Mr Sunak undertook to “push” officials to consider Mr Cameron’s request for financial assistance from the taxpayer for his clients. They also had a 10-minute phone conversation. Mr Cameron also called economic secretary John Glen and financial secretary Jesse Norman about access to the Covid corporate finance facility (CCFF).

The various requests to the Treasury were unsuccessful. But we also know that Mr Cameron arranged with Mr Greensill to to have a drink with the health secretary, Matt Hancock, to discuss a scheme relating to NHS payrolls, which was adopted by some trusts.

The Boardman review will additionally examine the past relationship between Mr Cameron and Mr Greensill, when the businessman was an “adviser” on supply chain finance to Mr Cameron’s government.

Also of interest will be the relationship with the then cabinet secretary, Jeremy Heywood, a highly respected civil servant who had encountered Mr Greensill when he was seconded to Morgan Stanley, where Mr Greensill was developing his new financial tool. In due course, Mr Greensill was given a security pass for Downing Street, access to the government machine and, in 2017, a CBE. In due course, too, Mr Cameron was taken on as an adviser to Greensill, in a neat role reversal, with share options in Greensill Capital that once had the potential to be worth many millions of pounds, though now worthless. Mr Cameron, it is fair to say, was expected to have easier access to important people than the average regulated lobbyist.

As if to pre-empt Mr Boardman, Mr Cameron has now acknowledged that mistakes were made and that it would have been much better if he had just written a letter or two in the usual way: “I have reflected on this at length ... There are important lessons to be learnt. As a former prime minister, I accept that communications with government need to be done through only the most formal of channels, so there can be no room for misinterpretation.”

That may be true, but it does beg a few obvious questions. As the man who warned that lobbying was the “next big scandal waiting to happen” and who framed the rules on lobbyists, why could it be that he had then handily exempted ex-premiers and ex-ministers from chatting to their old mates? Why did he not go through formal channels at all? What is the practical difference between a lobbyist (regulated) and a “consultant lobbyist” such as Mr Cameron (not regulated). The answer to that would seem to be the size of their fees and the ability sometimes to operate without civil servant involvement and public scrutiny. Those things may be connected.

There is an informal, tacit, unwritten but powerful contract that has emerged in the past 40 years or so as business people have become more closely involved in government, and ex-politicians (in all parties) have become more interested in their incomes after they retire from public service. One former Labour minister, after all, once described himself as a “taxi for hire”, and that sums things up nicely. The usual pattern was for a former minister to be able to join and work for any number of companies and consultancies after a minimal period and after the most cursory of checks by a toothless committee. The “revolving door” between public service and the private sector began to revolve in the Thatcher era where, classically, a cabinet minister who had overseen a major privatisation would find themselves eventually invited to join the board of the companies they sold off or associated bodies. Much the same goes for ministers in charge of big procurement budgets, such as at defence or health.

The need for reform is obvious, and the obstacles to it equally so. It is hardly in the interests of minsters and senior civil servants to cut off the possibility of nice earners as they approach retirement. Opposition politicians apoplectic at the abuse or perceived abuse of power and brazen conflicts of interest suddenly find themselves relaxed about such things when they win power. As they discuss such matters around the cabinet table, they reflect on the realities of political life, and the income they need once the taxpayer is no longer underwriting their lifestyle.

At that point, they seem to become more receptive to the assumption, rarely explicitly stated, but commonplace and powerful, that a post-ministerial money-making is their reward for the sacrifices and (supposedly) low pay and measly perks they have to scrape by on in public service. Revealing, sensationalist lucrative memoirs, possibly not entirely objective; “teaching” roles; advocacy; speech-making and lecture tours; journalism; executive and non-executive directorships; chairing inquiries; commissions and quangos; lobbying; even turning up for panels and broadcast media – all these exploit their afterlife of “public service” for personal financial gain. It is hard to imagine it ever ending, though Mr Cameron has, clumsily, done some considerable damage to the usual custom and practice. He can’t be a popular man around the corridors of power these days.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments