What are the legal remedies the EU could use if the UK broke the withdrawal agreement?

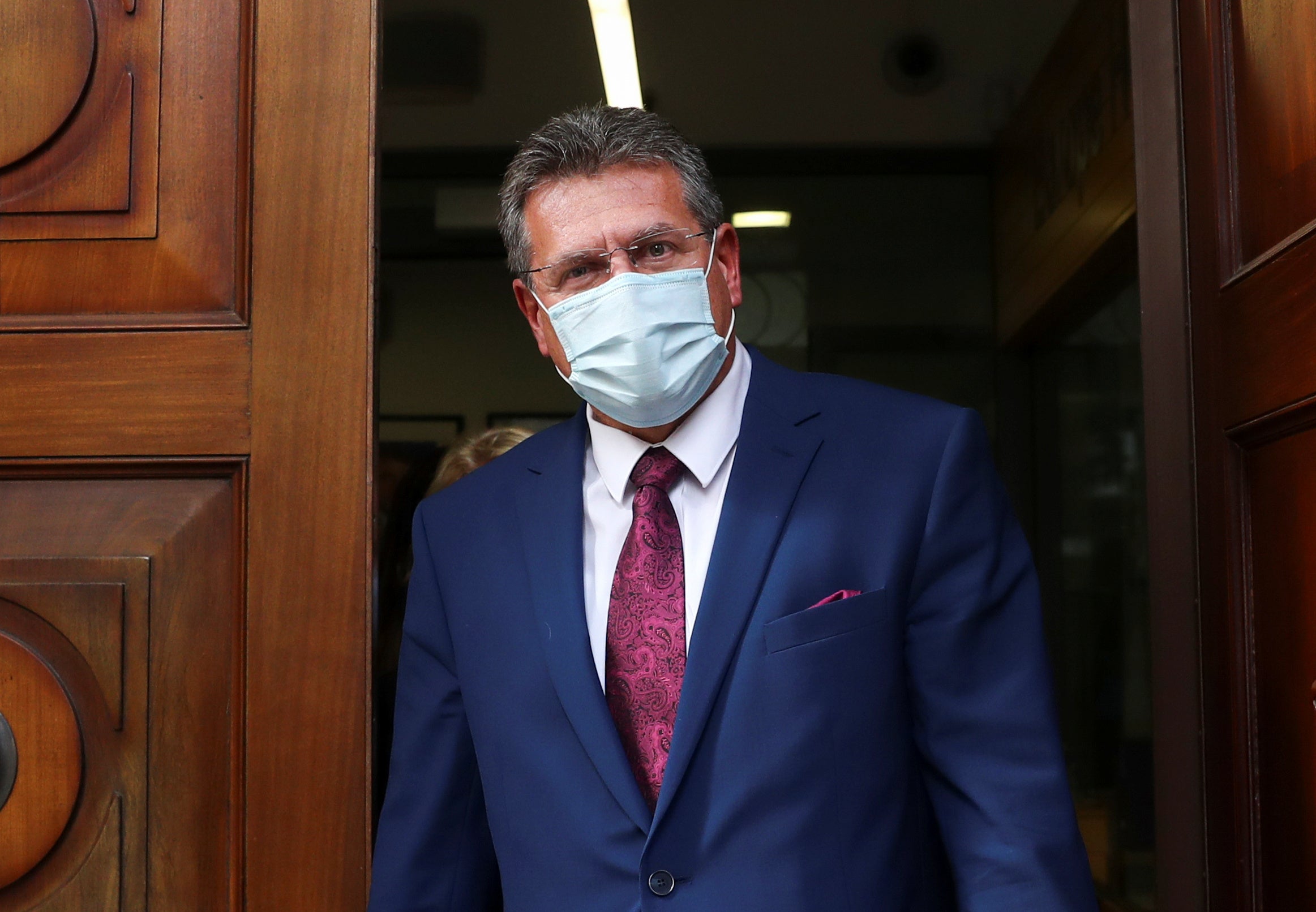

Maros Sefcovic, European Commission vice president, has threatened the UK with legal action if it breaks international law: John Rentoul explains the EU’s options

The European Commission responded furiously to the publication of the UK Internal Market Bill last week because it gives ministers the power to set aside some of the provisions of the withdrawal agreement by which the UK left the EU in January.

Maros Sefcovic, the commission vice-president, demanded a meeting with Michael Gove, the Cabinet Office minister, in London, and “reminded” him that the withdrawal agreement “contains a number of mechanisms and legal remedies to address violations of the legal obligations contained in the text – which the European Union will not be shy in using”.

But what are these “mechanisms and legal remedies”? He said there were a number of them, although that number is two. One is the Court of Justice of the EU, which retains the right to adjudicate on matters of EU law insofar as they affect the withdrawal agreement.

Given that one of the UK government’s requirements, under Theresa May and Boris Johnson, was that the CJEU should not have any jurisdiction in the UK, it seems surprising that this could be an option. However, as the dispute concerns EU internal market rules on state aid and exit declarations, it may be that an action could be brought there. That would invite the question of what would happen if the UK refused to accept the CJEU’s ruling, which would bring us the long way round to option two.

The other option is that the EU should follow the procedure set out in the withdrawal agreement for resolving disagreements about how it should be implemented. This is an elaborate system that avoids giving an advantage to either side. The agreement first requires both sides to try to resolve any dispute in the joint committee (which is currently headed by Gove and Sefcovic).

If they are unable to do so after three months, either side can request the establishment of an arbitration panel. The ruling of the panel “shall be binding on the Union and the United Kingdom”. This panel will consist of five people, two nominated by each side, and a chairperson jointly nominated by the EU and the UK.

If the EU and the UK are unable to agree on the selection of the chairperson within 15 days, either side “may request the Secretary-General of the Permanent Court of Arbitration to select the chairperson by lot from among the persons jointly proposed by the Union and the United Kingdom to act as chairperson”.

So, if it ever gets that far, the outcome of the dispute could be decided by the drawing of lots. The text of the agreement does not specify how this should be done – is it the roll of a die, or the drawing of pieces of paper out of a hat, or would there be lottery-style ping-pong balls in a transparent container?

Let us hope, if not for the reputations of Britain and the EU, at least for the dignity and solemnity of the idea of international law, that this argument does not come down to that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments