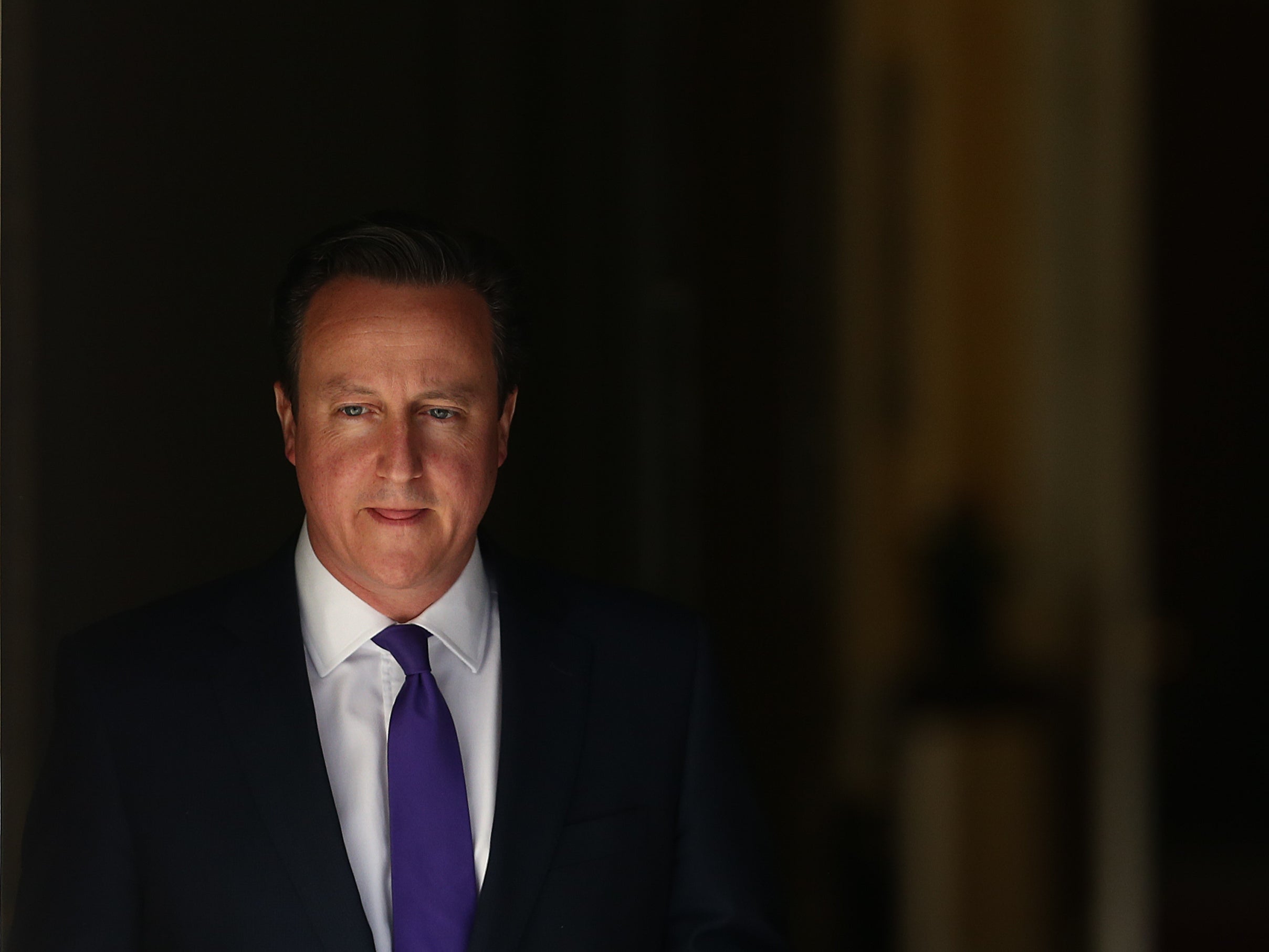

What next for David Cameron?

News of the Greensill affair has dealt the former prime minister’s already damaged reputation a further blow. Sean O’Grady considers where he goes from here

During his last months as leader of the opposition, after the MPs’ expenses scandal, David Cameron famously predicted that the next great scandal waiting to happen was in lobbying. Sure enough, three Labour ex-ministers were “stung” shortly afterwards by a newspaper, caught trying to peddle access during the dying months of Gordon Brown’s government. One, Stephen Byers, was unfortunate enough to have compared himself to a “taxi for hire”. At the time, Cameron reflected on the sorry state of affairs: “I think what it shows is a party that has been in power for far too long and has lost touch with what it's meant to be doing.” That has quite the echo now.

The conundrum at the centre of what we may now call the Cameron-Greensill affair is that, at least since Cameron left office, the only reason why Lex Greensill would find a clapped-out politician like the former prime minister useful is because of his connections. “Useful”, that is, to the extent that Cameron might once have been in line for share options in Greensill Capital worth about £50m. Even to a man as wealthy as him, that would qualify as “real money”.

For his part, Cameron, a man of intelligence and much political and diplomatic experience, had to offer his wise advice and, it turns out, his knowledge of the chancellor of the exchequer’s phone number, to which texts were dutifully delivered. There is nothing wrong with anyone wanting to make some cash, and no one has suggested any wrongdoing, but it is best to see the Cameron-Greensill relationship for what it was – a commercial, if not mercenary, one.

Read more:

The problem is that any former minister is only as much use to a commercial entity seeking government business as the “exclusive” access the ex-ministers can provide to current minsters and other people of interest; their contacts book, not their fund of anecdotes, is what the men and women of money want. The ex-ministers know how government works, who to approach, and how to do it. They do not usually have much else to offer. With rare exceptions, if they were cut out for business, they’d have gone into it.

But that access, if exercised exclusively, directly and “discreetly” – in effect, in secret – may not necessarily be in the public interest, even if is strictly within the letter of the law. If the law were drawn more widely, as figures such as Vince Cable suggested when he served in Cameron’s coalition government, then there wouldn’t be very much use in engaging ex-premiers and the like to make introductions and make cases on their behalf. There are professional lobbyists to do that and, a novel thought, there is nothing stopping the bankers and other businesspeople from picking up the phone and calling direct to government agencies and departments.

If there are “black arts” to lobbying, they exist in order to gain an unfair advantage for one commercial entity over another; again, that is not in the public interest. Just as concerning is the influence that “unpaid adviser” Greensill enjoyed from 2012 while Cameron was in No 10. His contribution to financing public sector projects may have been innovative and entirely benign, but no one seems to be quite sure about that. In any event, Greensill Capital went bust earlier this year, leaving what’s left of the British steel industry in jeopardy. The connection with the former prime minister has flattered neither side.

It may be that Cameron is worried for his financial future, or he may be plain bored. At 54, he is some way off getting a free bus pass to travel around his beloved Cotswolds on whatever rural services remain after a decade of austerity. Still energetic and thoughtful, he might also look enviously at the sort of fees that Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair commanded for personal appearances, or keynote speeches, and for their writing and continuing influence in world affairs many years after leaving office. Cameron’s less stellar former colleagues Nick Clegg (at Facebook) and George Osborne (with a new portfolio career combining journalism and finance) are also ahead in the earnings stakes. No doubt, when the time comes, Boris Johnson’s life after Downing Street will also meet his various financial obligations, if his earnings before he took office are anything to go by. Theresa May, John Major and Gordon Brown seem content with their lot, seemingly accepting their “B” class political celebrity status and making the best of it. May even stayed in the Commons, the better to troll her successor. Further back, Ted Heath, premier for less than four years, overcame rejection and reverses by simply pretending that he was still actually the real prime minister, and the temporary victim of some elaborate hoax of the gods.

Cameron’s problem is simply that his personal political failure over the Brexit referendum was so historic, so transcending and so final, that it has damaged his reputation and rendered him virtually friendless. It was he who reassured worried colleagues in 2016, “I can handle this,” and we all know what happened next. Johnson’s Brexit-driven populist administration barely acknowledges his existence, and when it does, it seems to regard it as some sort of centrist “elite” aberration, even though Cameron and Johnson were both Bullingdon boys together. As Cameron’s slow-selling memoir reminds us, he has little affection for former associates such as Johnson and Michael Gove.

Remainers and the remnants of the pre-Johnson-era moderate, pro-Europe Conservative Party rightly blame Cameron for overreaching himself. Both sides now take enormous pleasure in his lack of popularity. Thatcher and Blair, who still stir up plenty of hatred for what they did in power, at least have a considerable fan base, and a kind of grudging respect among their enemies. Cameron, by contrast, has been reduced to the status of a taxi no one wants to get into. At least he has not, yet, been reduced, like Nigel Farage, to offering video birthday greetings via the Cameo website for £75 a pop. Yet his enforced retirement seems less than golden. As he once said, rather cruelly to a by-then-embattled Blair: he was the future, once.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments