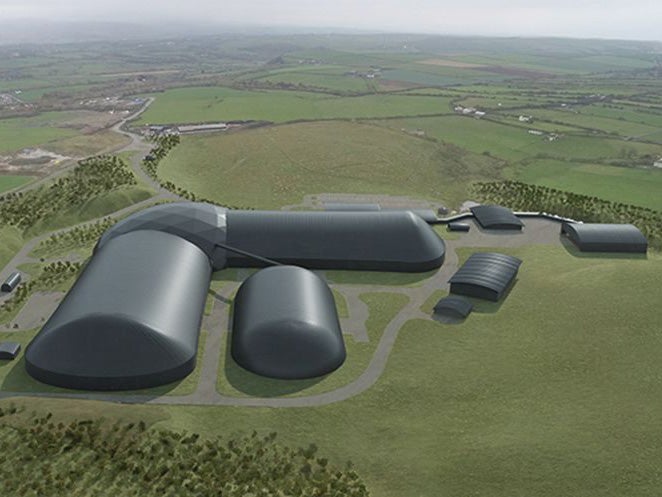

What do plans for a new coal mine say about Britain’s climate leadership?

Stopping the development would set a fine example to the world – and demonstrate how a democratic country can take tough decisions, writes Sean O'Grady

It cannot be comfortable for the prime minister to come under sustained criticism from leading environmental figures over a proposal to open one relatively small coal mine in Cumbria. Boris Johnson, sincerely or not, has put sustainability at the core of his “build back better” policy, has set ever more exacting deadlines to reduce CO2 emissions and has placed huge importance on the Cop26 international climate conference in Glasgow scheduled for November.

And yet James Hansen, the “godfather of climate change” and one of the world’s leading scientists, says in an open letter that Mr Johnson risks “humiliation” if he doesn’t somehow intervene to stop the pit. It will create precious jobs in a “left behind” part of the north, precisely the kind of place Mr Johnson’s “people’s government” pledged to “level up”. The coal mining scheme was granted planning permission from the local authority, and the communities secretary Robert Jenrick, has upheld the decision. Downing Street says the decision will not be overruled by Mr Johnson. That doesn’t, of course, rule out a U-turn.

For a government that likes to boast about its green credentials, the new coal mine is deeply embarrassing. It joins the HS2 line and the expansion of Heathrow as symbols of green hypocrisy on the part of the government, no matter about its plans to phase out petrol and diesel cars. In the case of the new coal mine, the arguments are especially complicated.

The coal that comes from the mine is essential for steel production. This is not because it is used directly to generate heat to produce the steel – that energy can come from renewables powering electric furnaces. Rather, the Cumbrian operation will mine coking coal, the coal itself becoming an ingredient in the steel. After heat treatment the coal is purified and turned into a coke, a more pure form of carbon. Added to the iron or iron ore, coke, ie carbon, forms an alloy – steel.

The argument is thus essentially an economical and societal one about the demand for steel, and what steel is used for. If the world had no use for steel, there would be no need for coking coal. That, though, would mean we had less demand for cars, consumer durables, railway tracks, steel girders for buildings, ships, machinery, paper clips and anything containing steel.

Can steel be made with a different source of carbon? Theoretically yes, but the alternatives are not the norm and are slightly cranky. We could go back to the pre-industrial system of using (ie burning) timber to create charcoal as the carbon precursor. Trees are “renewable”, but only slowly and charcoal production generally leads to deforestation. An Australian firm has found a way to use scrap tyres, but that might not be so green due to the energy used in gathering, transporting and processing them into pure carbon.

Steel too has its alternatives, usually with environmental and other drawbacks – aluminium (energy intensive and expensive), plastics, iron and wood have more limited applications. A lot of steel will be required to build all those new electric cars. Steel is strong, malleable (for pressing into panels) and light and often the greenest practical option.

So stopping the Cumbria mine might make no difference if the coking coal was then instead imported from America or Australia, or if more UK steel production went off to China, say. The 400,000 additional tonnes of greenhouse gases annually emitted by the Cumbrian coal is unwelcome; but the context is a UK total annual output of around 350 million tons. And, to reiterate, the emissions would simply be exported.

The Cumbrian mine remains, though, a powerful symbol of Britain’s global environmental leadership, or lack of it. Stopping its development would set a fine example to the world, and demonstrate how a democratic country can take tough decisions. It would help Britain meet its carbon reduction targets, and the government could extend its activism by making the British steel less dependent on coking coal and the greenest steel industry in the world. The UK’s remaining steel manufacturers could certainly use a technological edge. Mr Johnson often talks in bright terms of the British talent for innovation to meet seemingly impossible demands. Rather than digging up coal, a clean, green high-quality low-carbon steel could be a more attractive industrial scheme to debate in the conference hall in Glasgow come November.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments