What is happening with the government’s coronavirus testing figures?

The latest move to end publication of a key statistic has provoked accusations of a cover-up – but a cock-up is the more likely story, writes Sean O'Grady

For six weeks the government has suspended the publication of the definitive number of people tested for Covid-19.

Some figures on total numbers of tests, on new confirmed cases and on deaths are being released onto the official Covid-19 “dashboard”, but not recently have we seen the actual figure the government used to focus on as the key target.

Now the figure will not be published on any regular basis, and possibly ever. Given that one of the few clear goals in the government’s strategy for beating coronavirus has been that “audacious” target of 100,000 people per day, it will no longer be possible to see how well the testing system is responding to the challenge.

It adds to a general impression of confusion and failure on testing in the UK. Testing, it is widely thought, was abandoned early in the epidemic, probably due to a severe shortage of kits and chemicals, and has been symbolised by the botched testing of the much-postponed app, for which there were once such high hopes.

Now the public health of the nation depends on publicans taking the contact details of their customers and for those affected to cooperate. This may not prove a wholly comprehensive approach, given the factor of early asymptomatic spread and exponential growth in infections.

This latest move to end publication of a key statistic has provoked accusations of a cover-up, of ministers trying again to evade scrutiny and avoid blame for what has gone wrong. The British public will now never know if the revised target of 200,000 tests per day (ie people tested) by 1 June was ever reached. It is unlikely, though.

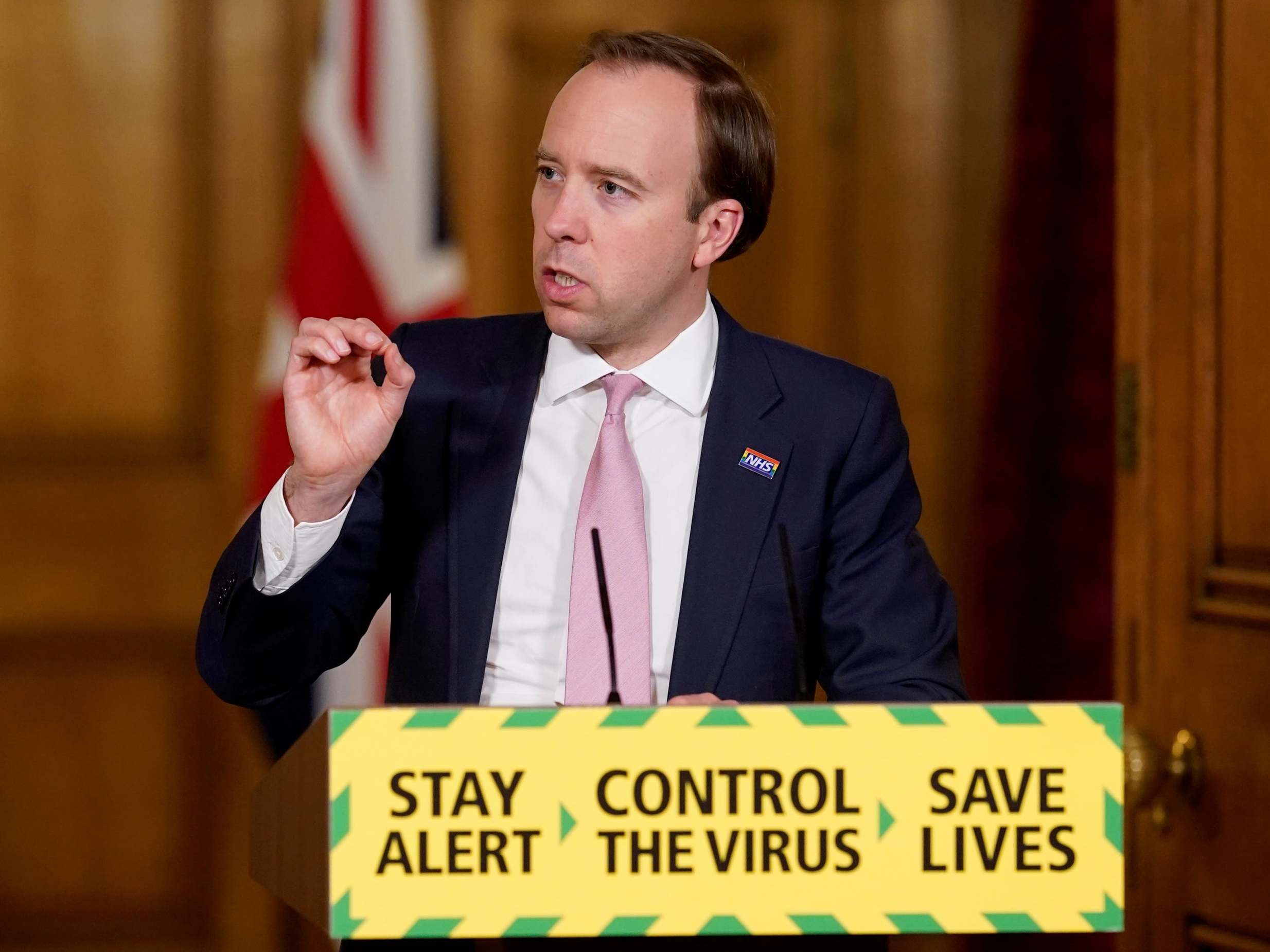

As with so much around Britain’s testing regime, it is a messy, not to say distressing, picture, but the truth about the daily number of people tested may be more to do with cock-up than conspiracy, though that is hardly reassuring in the circumstances. It seems, in other words, that Matt Hancock, the health secretary, under intense public pressure targeted the wrong metric in the first place.

On 2 April he announced that in England there would be 100,000 tests per day, by the end of the month. Arguably it was met by the deadline, in terms of “capacity”, before in any case falling back and then being abandoned. There are a few clues as to why this was not only an overambitious target, but an impractical one statistically.

First, we have the simple fact that many people, particularly working in hospitals or being treated there, are tested more than once, sometimes over a relatively short time scale, but always a variable one. This happens because people can show potential symptoms more than once, for example, or do so in different locations, or the test may yield a suspicious negative and have to be done again.

Double counting becomes a real problem in such circumstances. Having 50,000 people tested twice is not the same as 100,000 people tested once. True, it is the number tested which is crucial, but it seems the method for recoding the data is inadequate to the task of coming up with a definitive number. That may, of course, be politically convenient if the target was never going to be met.

Another clue giving credence to this is the explanation given by the Department of Health when the personal testing figures were suspended: “Reporting on the number of people tested has been temporarily paused to ensure consistent reporting across pillars.”

That referred to the four streams of testing and data that were coming into government, with only the first being by then regularly released:

* Pillar 1: testing in hospitals to see if people have Covid-19

* Pillar 2: testing at public drive-through centres to see if people have Covid-19

* Pillar 3: testing of people to see if they have had Covid-19 (and thus antibodies and potential immunity)

* Pillar 4: highly sensitive, super-accurate testing at Porton Down of a sample of the population to see exactly how many people have had Covid-19, sometimes without realising it.

A further clue was the way that Mr Hancock greeted the “achievement” of the target at the end of April by counting kits sent out but not yet returned – which turns out to be possibly quite large – and figures for people tested more than once, under one pillar or another.

There is also the fact that testing numbers, even if accurate, cannot easily tell the story about infection, recovery rates or herd immunity simply because a sizeable number of (especially) younger people get through the illness with only the mildest if symptoms and don’t bother with any test. And, as Donald Trump points out, more testing can mean more cases being identified, though the real world picture may be actually better or worse than testing numbers suggest because the cases identified through bigger or smaller testing programmes can never be the total. In the UK the best guess is that testing has been rising, but infections falling or stable; in significant parts of the US both testing and infections are rising.

The best estimates from the ONS suggest only something like 7 per cent in England had had Covid-19 (as of the end of June), on a survey basis involving testing for antibodies, which is way lower than the number needed for herd immunity.

The point about the testing regime during the lockdown back in April is that it would help to prevent a surge in cases overwhelming the NHS. That is still the point, with much more emphasis on local control of outbreaks as in Weston-super-Mare, Kirklees and Leicester. The worrying development there is that not enough timely detailed information (the Pillar 2 numbers) was given to Leicester City Council, and shadow health secretary and constituency MP John Ashworth says it is still not flowing through.

If the testing regime is now the UK’s main line of defence against local and national second waves then all the available data does point to it continuing. Leaving aside the media and public, if there is data and personal information that it has not been possible to even collate and to pass on to concerned public health authorities, to trace and isolate cases, then the outlook for a second peak arriving as lockdown eases is bleak indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments