Why election bias accusations put the BBC under threat

All political parties think the broadcaster is against them, writes Sean O'Grady

The BBC is used to being attacked by politicians. It comes with the territory. Ever since, in its very first years, it survived its first run-in with a politician on the make by the name of Winston Churchill (that was over the General Strike of 1926), it has had to deal routinely with politically motivated claims of political bias. As well as Churchill, politicians as diverse as Tony Benn, Harold Wilson, Margaret Thatcher, Norman Tebbit, Tony Blair and George Osborne have either loathed it, threatened it, sought to undermine it – or, sometimes, all three.

Still, the range and ferocity of the fire being directed at the broadcaster and its journalists in recent times is of an unprecedented degree.

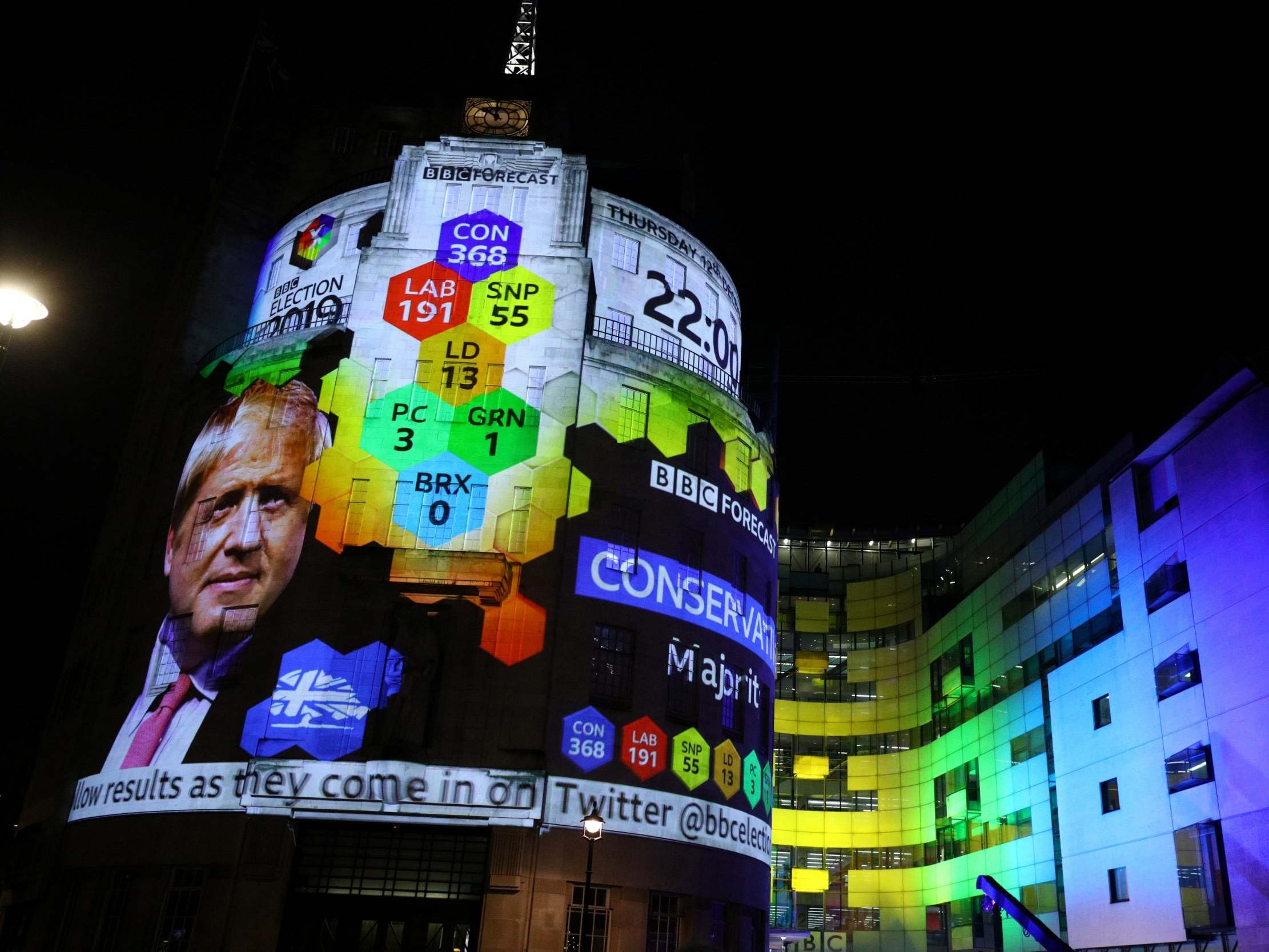

In our fractured political culture, our leaders can agree on one thing at least: the BBC is institutionally biased against them. All of them. Logically it cannot be true, but that has not stopped the run of complaints. Nigel Farage has attacked the BBC for its audience selection (and was memorably rebuked and his claims rebutted by David Dimbleby). Remainers by contrast, protest that Farage is never off their screens. Jo Swinson, before her downfall, also accused the BBC of audience bias, and for not inviting her on to the stage with Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn for the leaders’ debates. Labour now see the BBC as part of a “mainstream media” with its own anti-Labour, anti-Corbyn agenda. A shadow cabinet mister, Andy McDonald, goes so far as to say that the broadcaster had been “consciously” biased during the campaign and suggested that its executives should “have a look in the mirror”. The BBC, according to McDonald, had “played a part” in Labour losing and claimed that Corbyn had been “vilified” and “much-maligned”.

For their part, the Conservatives have long regarded the BBC as a part of some liberal elite, packed full of lefties. Johnson has termed it the “Brexit Bashing Corporation”. Leavers objected to “good news” stories about that economy (apocryphal or not) being prefaced with the words “despite Brexit”. The former editor of The Daily Telegraph, Charles Moore, refuses to pay his licence fee. After the loss of the 2014 independence referendum, the SNP organised what amounted to a mob to picket the BBC head office in Glasgow in protest against, yes indeed, BBC bias.

Well, as BBC folk often reply, their critics cannot all be right. Or at least they cannot all be right simultaneously. As Andrew Neil points out, the only bias the BBC has (and should have) is a bias towards the truth.

In reality, in the modern era of social media, fake news and bot farms producing bogus tweets, Facebook-published propaganda masquerading as advertising and a “wild west” level of regulation, the BBC is a rare and unbiased source of fact-checking, straight stories and strong, unskewed analysis.

The public has always had the BBC (as well as ITV News, formerly ITN) to counter the partisan press; the need for such a news service has never been greater. As such, the BBC, like that other great national institution the NHS, generally enjoys the affectionate support of the public. Voters, as viewers and listeners and the vast global audience for the website, appreciate what it does far more than the politicians do. That should give any government pause for thought before it starts to vandalise one of Britain’s few world-class brands, state-owned or not.

The BBC has managed to find its way through many crises. It has been in mortal danger over its coverage of the Suez Crisis, Falklands War, the bombing of Libya in the 1980s, the IRA, strikes, spies, and, of course, the Iraq War and the Gilligan Affair – which saw the departure of the BBC’s chair and director general.

Now, though, the prime minister himself is thinking aloud about the future of the licence fee, the very basis of the unique way the BBC is able to function. Decriminalising the offence of not owning a TV licence is viewed as the thin end of a financial squeeze; the Conservative promise to continue to make the BBC administer free licences for the over-75s is another prong in what could be a damaging assault on the BBC’s ability to fund its work.

Against that, though, is the commercial reality of the internet, the streaming services and the arrival of who-knows-what future new channels to rival the BBC’s historic mission to inform, to educate and to entertain. The licence fee and its limited commercial activities do not provide the BBC with sufficient cash to compete easily with the likes of Netflix and other US-based media giants. The recent launch of BritBox was an attempt to offer some solution through partial subscription/premium services to that commercial conundrum.

The good news for the corporation is that, unlike the far more vulnerable Channel 4 (a broadcaster even more out of favour in Conservative circles) the BBC is not founded upon the usual Act of Parliament but a Royal Charter. As with universities and other bodies, it gives the BBC much greater protection from interference by government.

The current charter is not due for renewal until towards the end of the 2020s, and so the BBC is not in immediate peril. However, as the charter renewal process picks up under the present administration there may be a chilling effect on the way the BBC’s journalists report on current affairs, for fear of upsetting ministers and jeopardising their own future. How far the BBC and its staff manage to protect their core values and mission as they approach its centenary year, 2022, and beyond is crucial. It may boil down to a popularity contest between the BBC and the Johnson government.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments