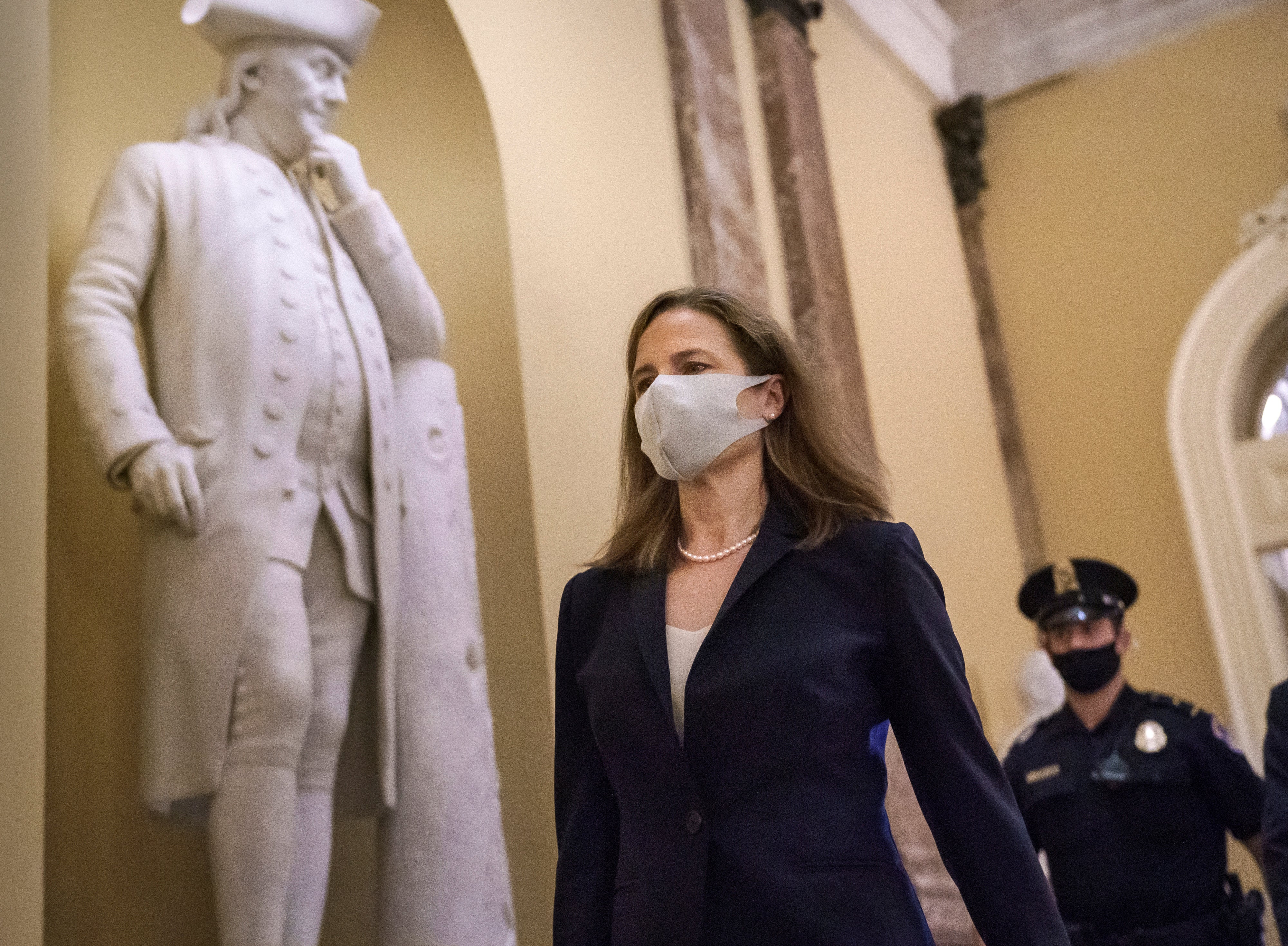

What difference will Amy Coney Barrett make to American politics?

The appointment of Barrett to the Supreme Court seals for the foreseeable future a 6-3 conservative majority in the top US judicial body. Sean O’Grady considers Democrats’ fears and what Joe Biden could do to allay them if he is elected

Now that Amy Coney Barrett has been appointed to the Supreme Court, what difference will she make?

Going by her past remarks and judgments, it seems likely that Barrett will be as reliably conservative as her predecessor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, was generally liberal in outlook. This, in doctrinal terms, is exemplified in Barrett’s “originalist” view of the US constitution – the concept that it means now what it meant at the time, which for many parts goes back to the 18th and 19th centuries. That is an even more fundamentalist approach than the “constructionalism” of the past, which was to take the constitution at its word, without undue interpretation – still less, legal “activism”. So the new judge may be thought of as a social and legal conservative.

That has distressed some liberals who fear, for example, the protection of gun ownership and a weakening of abortion rights. They also object to the violation of the convention that a justice should not be appointed so close to a presidential election.

Yet there is nothing in the constitution about not appointing justices in an election year, and there are precedents for attempts to do so, such as by the outgoing Lyndon Johnson in 1968.

As for Barrett’s attitudes, the fact has to be faced that hers are not so outlandish given the current complexion of American politics. The nation has a Republican president and a Republican Senate, and more than a quarter of Americans are evangelical Christians. They might all be wrong about everything, but they represent a sizeable proportion of the electorate. Besides, the Supreme Court is not an institution that is supposed to closely represent public opinion; the legislative and executive branches are supposed to do that.

That said, overtly political appointments are, if anything, less common than in the past. The Republican president William Howard Taft went on to serve as chief justice through the 1920s, to take one extreme example. Earl Warren, for another instance, was appointed by the Republican Dwight Eisenhower in 1953. Ike declared: “He represents the kind of political, economic, and social thinking that I believe we need in the Supreme Court.” Warren had served as Republican governor of California and had tried to secure the vice-presidential nomination for his party. Nonetheless, he became a distinguished liberal Republican voice during the struggle for civil rights. In a similar manner, Chief Justice Warren Burger, appointed by Richard Nixon, supported the landmark Roe v Wade ruling of 1973, which might not have been what Nixon had in mind when he selected him. (Nixon, by the way, also considered appointing Burger as vice-president when a vacancy arose, blurring the political-judicial line again.)

Judges, who cannot be removed, can anyway evolve their views over time, and move in all kinds of directions, springing the odd surprise. Perhaps the most distinguished member of the Supreme Court, Louis Brandeis was virtually a socialist, but still kept to his own independent reasoning over President Roosevelt’s New Deal. They are open to reason, at least sometimes, and much of their work is not directly political.

Of course, President Biden, if elected, could attempt to reform the court, or “pack it”, according to his critics, who suspect he would try to stuff the bench with liberals. The number of justices is a matter of statute rather than specified in the constitution (ironically, for the constructionalist/originalist wing).

Yet all Biden is proposing for now is a bipartisan “commission” to look at whether the court is “out of kilter”, as he terms it.

Were he to try to make a move to expand the membership to 11, say, he might find it difficult to get that through the Senate. The precedents are only partially encouraging. When some of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal laws were struck down in the 1930s, he proposed to retire judges compulsorily at 70, and had a bill ready to pass into law through the Democrat-dominated Congress, the landslide of 1936 representing a sort of mandate to push the Supreme Court back. In the event, the court changed its mind and the bill was never needed.

Yet that also illustrates how double-edged reforming the Supreme Court could be. Roosevelt wanted to sack aged conservatives – but had his proposed 1937 law been in force in the 2000s and 2010s, it could have been used to kick Ginsburg off the bench. A future Republican president in league with a Republican Congress could inflate and pack a Supreme Court of 13 or 15 justices.

As American politics grows more bitterly and more closely, evenly divided, the Supreme Court may be asked to do more things that should probably belong in the political sphere, because the democratic institutions cannot agree. When the checks and balances start to seize up, the Supreme Court sometimes has to cut the Gordian knot in the most difficult of crises, as with Watergate and the contested presidential election in 2000. Soon it will probably be asked to do so again. No doubt Chief Justice Roberts will perform his duties professionally, without fear of favour, but the controversy over Barrett will probably harm the court’s reputation for independence. It is just the latest arm of the American state to be infected with the weakness that is sapping the strength and authority of all America’s institutions. In 2000, its judgment in favour of George W Bush was grudgingly accepted; would that be true for a pro-Trump ruling now? Something for Associate Justice Barrett to ponder.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments