Book of a Lifetime: The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard

From The Independent archive: Ken Worpole on a highly original study of the magical ‘cosmos’ of the childhood home

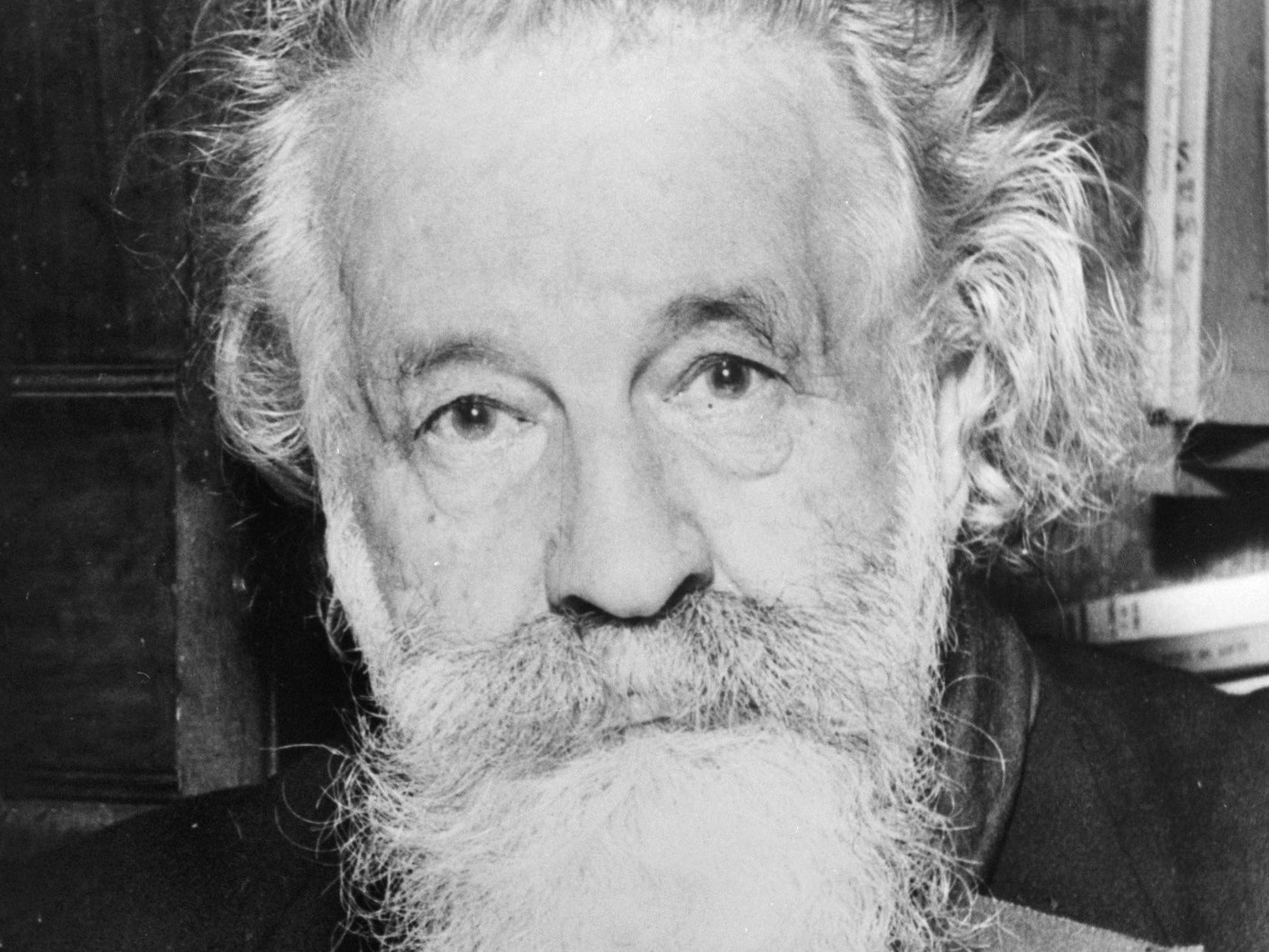

In a tumbledown cottage the wood-cutter’s daughter dreams of life in the palace; in the palace the young prince believes that in a forest hut lives the woman he is destined to love and marry. Folk tales – with their Gothic illustrations – endure through the romance of mountain turrets, forest interiors, lonely cottages, magic casements and secret doors. This is what the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard called “the poetics of space”, and his highly original study of the magical “cosmos” of the childhood home and its imaginary spaces is one of the few literary texts that architectural students are required to read.

In the 20th century, distinctions between public and private space were challenged by rationalist architecture and town planning. Bachelard explored a third kind of space, the “felicitous” space of the home and its domestic menagerie of tables, chairs, cupboards and stairs. He was fascinated by the life-worlds of the attic and the cellar, and their distinctive dreams. That objects embody deep emotional reserves was explored in delightful musical works by Milhaud and Ravel, both of whom, like their compatriot Bachelard, were entranced by the work of poets such as Maeterlinck and Rilke. Not only was small beautiful, but it was more conducive to the imagination.

Architects will tell you that designing intimate buildings is much more difficult than erecting monoliths. Those I have talked to in writing a book about the new hospice movement have employed Bachelard’s vocabulary of intimacy; they have described the need to create distinct psychological thresholds between open and closed, inside and outside, arrival and departure. Places of helpless waiting are refashioned in the hospice as places of contemplation and a gathering-in of memory and self-discovery.

Bachelard was a phenomenologist, holding the view that there was a dynamic interplay between an active mind and its surroundings. The house was a theatre, something most people realise when travelling by train through the city at night, seeing lighted interiors. A candlelight in a window was enough to bring a street to life, he wrote. The author of The Poetics of Space showed no interest in buildings other than the domestic house. Most meaningful relationships with buildings take place in domestic space, and this is what modern hospices have sought to emulate.

In the Maggie’s Cancer Care centres, the building is designed around the hearth and kitchen table. In the first and last days of life, it is the cosmos of the home that takes on the full weight of human habitation, as retreat and space of belonging. Bachelard’s greatest work remains a compelling reflection on the enduring human need to find psychological refuge in familiar places and spaces, though its author admitted that poets and storytellers got there first.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments