Was Pliny the Elder’s heroic death in the face of Pompeii’s destruction a work of fiction?

We’re told by his nephew, Pliny the Younger, that the ancient polymath was found ‘intact and uninjured’ after the eruption of Vesuvius. But, as Kevin Childs suggests, there is very little evidence

He died in a catastrophe which destroyed the loveliest region of the earth, a fate shared by whole cities and their people, and one so memorable that it is likely to make his name live forever.”

The ancient Roman writer, Pliny the Younger, begins his description of his uncle’s death by conjuring up an event which had already become legend by the time he memorialised it. He was writing to the historian Tacitus many years later. The uncle, known as Pliny the Elder, was one of the most famous victims of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD79 which buried “whole cities and their people” under ash. Pliny the Elder’s death was important to Tacitus because he was a famous author – his magisterial Natural History is still read today for its insights into the ancient world. Pliny the Elder was also the hero of Vesuvius. Not content to observe the disaster unfold before his eyes, he put himself in peril to help those trying to flee the volcano, launching the first humanitarian rescue mission in recorded history.

Recent reports from Italy say they’ve identified his skull, or part of it. The fragments of bone were dug up in 1900 near the site of the ancient town of Stabiae on the Bay of Naples, along with some highly significant jewellery and equipment – a fancy sword of the type carried by senior naval officers, a chain of office, a gold ring and distinctive gold bracelets. Dismissed at the time as improbable fantasy, the bones have been subjected to modern forensic testing and the result is that, almost certainly, they do indeed belong to Pliny the Elder.

His nephew’s letter is the only eyewitness account we have to the most significant catastrophic event in the ancient world. Pliny the Younger was 17 at the time. Since his father’s death, he and his mother had been living with his uncle, and in the golden autumn days of AD79, their house was in Misenum, on the northwest point of the Bay of Naples, that “loveliest region of the earth” where the elder Pliny was the admiral of the fleet.

It was young Pliny’s mother Marcella who first noticed the odd, menacing cloud hanging over Vesuvius, a plume of white ash which then spread out “like an umbrella pine” he would write, and she pointed it out to her brother, the elder Pliny. His interest was piqued: here was a phenomenon he’d never witnessed, a volcanic eruption. He would investigate. At this point he didn’t think about any danger. He invited his nephew to join him on the expedition, but Pliny the Younger declined, reminding his uncle that he had to finish his studies.

As he was leaving, a message from a friend across the bay arrived begging for assistance. People trapped between the raging mountain and the sea had nowhere to go. Pliny the Elder ordered the fleet to set sail to help evacuate the populations of the holiday cities along the coast. “[W]hat he had started in a spirit of scientific enquiry,“ wrote his nephew, “he ended heroically.”

The shoreline they approached was changing rapidly, growing black, jagged and the sea was becoming shallower. Ash and pumice dropped in heavy showers, threatening to sink some of the vessels. Light faded as if night had fallen in the middle of the afternoon. A landing in any of the harbours looked impossible. The helmsman advised turning back. “Fortune favours the brave,” Pliny the Elder declared. He’d been making observations of the eruption all throughout the voyage. He wasn’t going back now. Instead he ordered a change of course, plunging his ship through the steaming, hissing waves towards the seaside resort of Stabiae on the southeast corner of the bay. He judged that the people there were not yet affected by the eruption. But his observations of the great cloud gathering overhead suggested it would only be a matter of time. The spirit of enquiry was turning into a desperate race against the mountain.

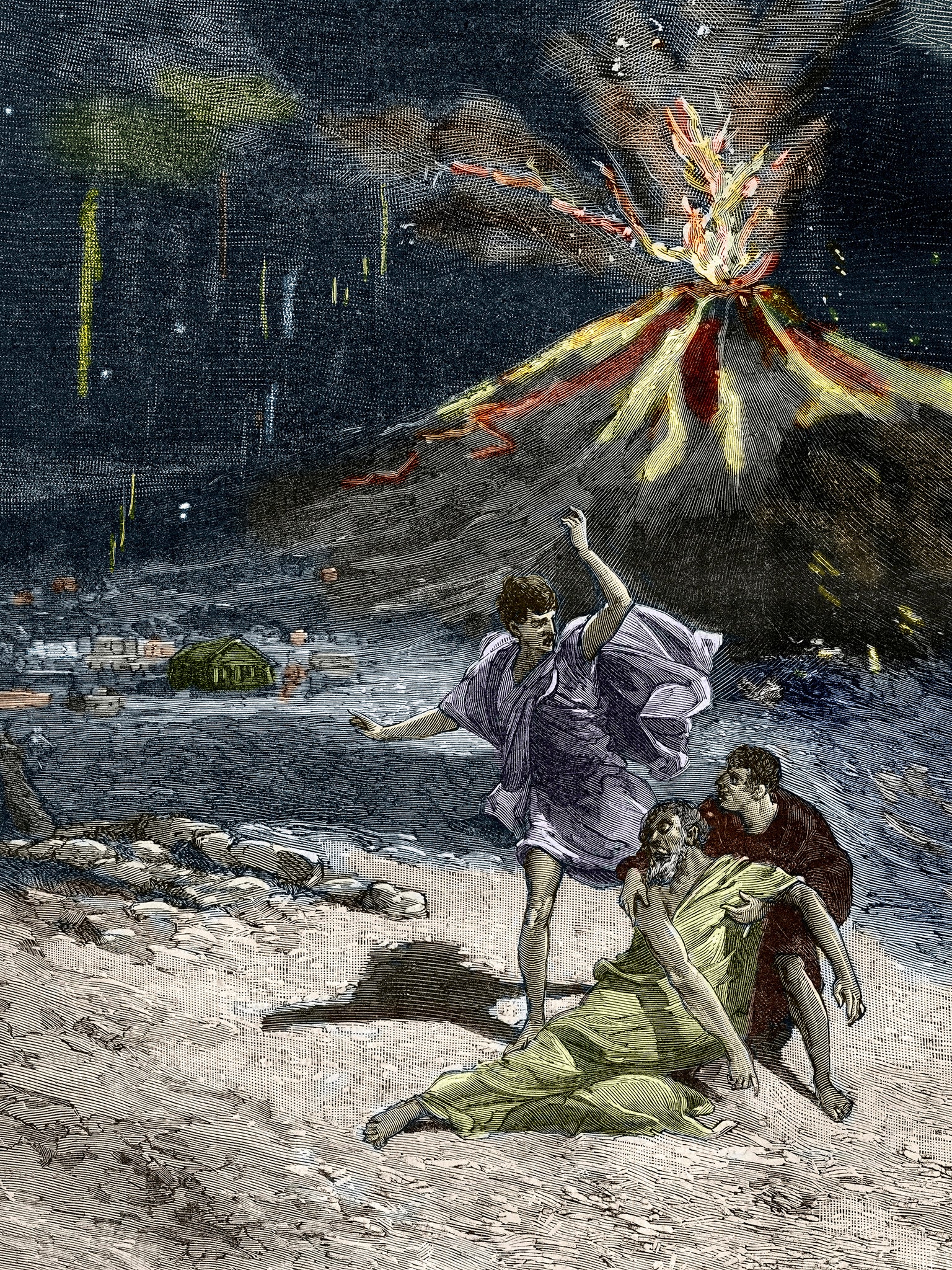

Once on dry land, Pliny the Elder realised that the wind which had sped him there now trapped him. He tried to rally the people there, dining in one of the sumptuous villas which lined the sea front, even suggesting they just sleep out the eruption until a favourable wind allowed them to put to sea. By the early hours pumice and ash was filling up the courtyard and the frequent earth tremors in the pitch-black darkness meant their villa was in danger of being buried, so they went out, running up and down the beach with torches and lamps showing only the constant fall of ash, pillows tied to their heads to ward off chunks of hot rock and pumice.

Wind and sea were still against them. Pliny asked for water and lay down to rest on a sail cloth. He wasn’t feeling well. A sudden explosion of fire and the smell of sulphur caused the rest of the group to scatter. Pliny tried to get up, helped by two slaves, but fell back and died instantly. The people he’d come to rescue lived to tell the tale to his nephew.

Forensic science can determine age, health, ethnicity, even pinpoint where someone was born, in Pliny the Elder’s case Como, from a small fragment of bone. A lower jawbone was also unearthed, along with a skull, and was long-thought to have belonged to the old polymath. But the recent tests suggest that the jawbone belonged to a younger man, well over six feet tall and probably of African origin. Could this be one of the slaves who stayed with Pliny according to his nephew’s account, and presumably perished with him in the eruption’s final, most violent stage, fused in death so thoroughly they were thought to be one and same man for over a hundred years?

We have no physical remains of any of the famous men and women of western antiquity: no Caesar or Alexander, no Antony or Cleopatra, no Plato or Sappho. The discovery of the top of Pliny the Elder’s head is a remarkable find. But its survival also casts a doubt over his nephew’s account of his death. There are controversies over Pliny the Younger’s dating of the eruption to late August. More pertinently, however, Pliny ends his letter to Tacitus with a passage that seems to contradict the forensic evidence of these remains:

“When daylight returned … His body was found intact and uninjured, still fully clothed and looking more like sleep that death.”

Two metres of ash had fallen over the preceding 48 hours and so his companions would have had to dig for his body. If Pliny were the victim of a 300C pyroclastic surge, as the account implies, it’s unlikely he’d look so intact and peaceful. Most of those who died were incinerated by waves of super-hot gases, one skull had its brain turned to glass by the heat. But the really serious discrepancy is this: surely his friends would have taken the body away for proper cremation, not left it in the ash and pumice of a wrecked seaside resort to be excavated nearly two millennia later. If Pliny’s account were accurate, how could this partial skull in a museum in Rome be his uncle’s?

Or was Pliny the Younger correcting the account to give his uncle’s body a sort of miraculous preservation, a more suitable ending for Tacitus’s purposes. If these remains are Pliny the Elder’s, then his friends did not return to find his body, or in doing so they failed to locate it. It was a pious duty to honour the dead. Maybe the nephew, unable to do this in life, did so in his account of his uncle’s heroic death.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments