Book of a Lifetime: Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens

From ‘The Independent’ archive: Shirley Williams looks at the dark imagery in one of the author’s most compelling novels

I am fortunate enough not to have had the novels of Dickens urged onto me as a child or been required to write about them at university. I encountered them properly in middle age and have re-read them with enormous pleasure since.

Our Mutual Friend may not be his greatest novel, but in some ways it is his most compelling. From the opening paragraph, the dark imagery comes straight off the page and into your visual imagination and, as an illustrator, I find it irresistible: the autumn evening closing in, the crazy little boat afloat on the filthy Thames, the strong young woman plying the oars and a ragged, grizzled man, her father, busying himself with something towed in the water behind them.

You are some way into the narrative before it dawns on you that it is a drowned body. They are at their evening’s work as scavengers of the river. You are transported to the brightly lit, highly varnished home of the nouveau riche Veneerings, where everything, including their friends, is new and full of hard reflections.

Perhaps, had Dickens lived in the 20th century, he might have become a great filmmaker. Even his ardent admirers might admit that some of his heroines are almost too good to be true. They often suffer from being outrageously put upon by weak, immature fathers, accepting the burden with uncomplaining loyalty. The two strong heroines of Our Mutual Friend, Lizzie Hexam and Bella Wilfer, are more human.

Places such as the ramshackle dwelling on the slimy riverbank, or the Boffins’ over-furnished home, or Mr Venus’s bizarre taxidermist shop – full of grotesque stuffed creatures and mummified human parts, where Mr Wegg calls in search of his amputated leg – are all meticulously described.

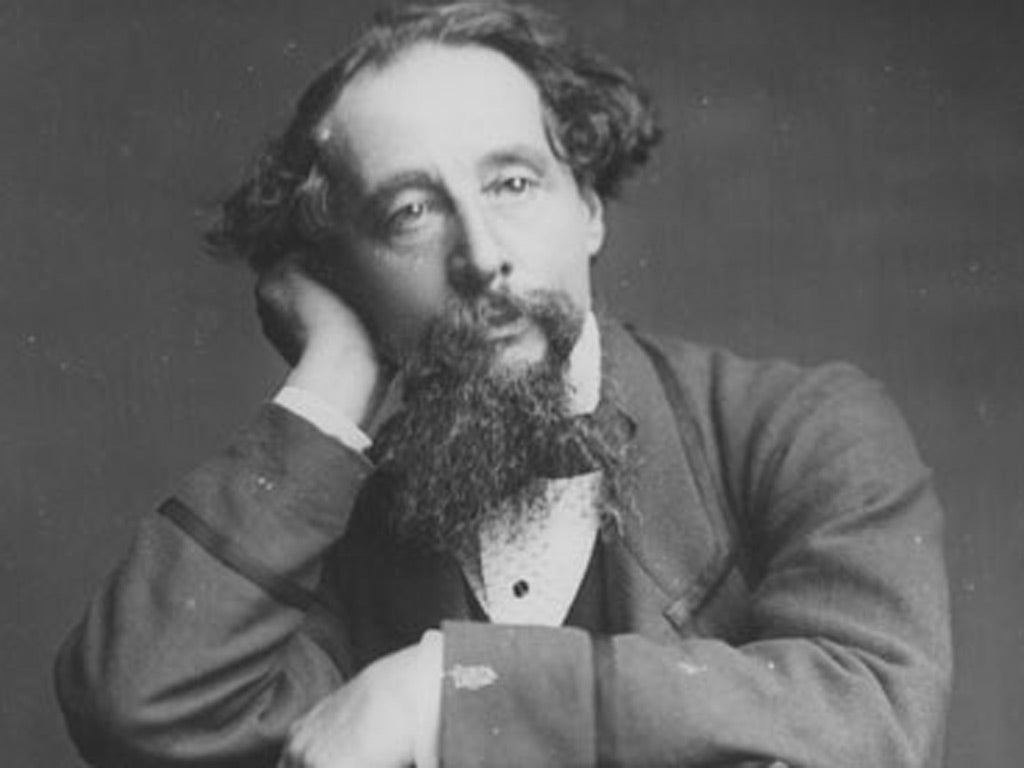

Marcus Stone, the narrative painter, was commissioned to do the first illustrations for the book. By all accounts Dickens was an exacting author to work with. His great partnership with Hablot K Browne, known as Phiz, was then over. Dickens had decided he needed a new interpretation and Phiz, like Mrs Dickens, was discarded. Sadly, Stone’s wood engravings failed to capture the darkly dramatic atmosphere.

Two powerful opposing elements dominate: the murky water of the Thames and the mountainous north London dust-heap composed of ashes from the city’s grates. Both are combed by poor scavengers hoping to find some pickings from which they can scratch a living. Both hold secrets crucial to the plot.

Upriver, at the climax of the novel, two men, Bradley Headstone and the villainous Riderhood, wrestle to the death by the weir. Their drowned bodies are found in the ooze behind the lock gates. What illustrator would not be tempted by the challenge of Our Mutual Friend? But I think I will stick with the pictures in my head. They are more vivid than any on the page.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments